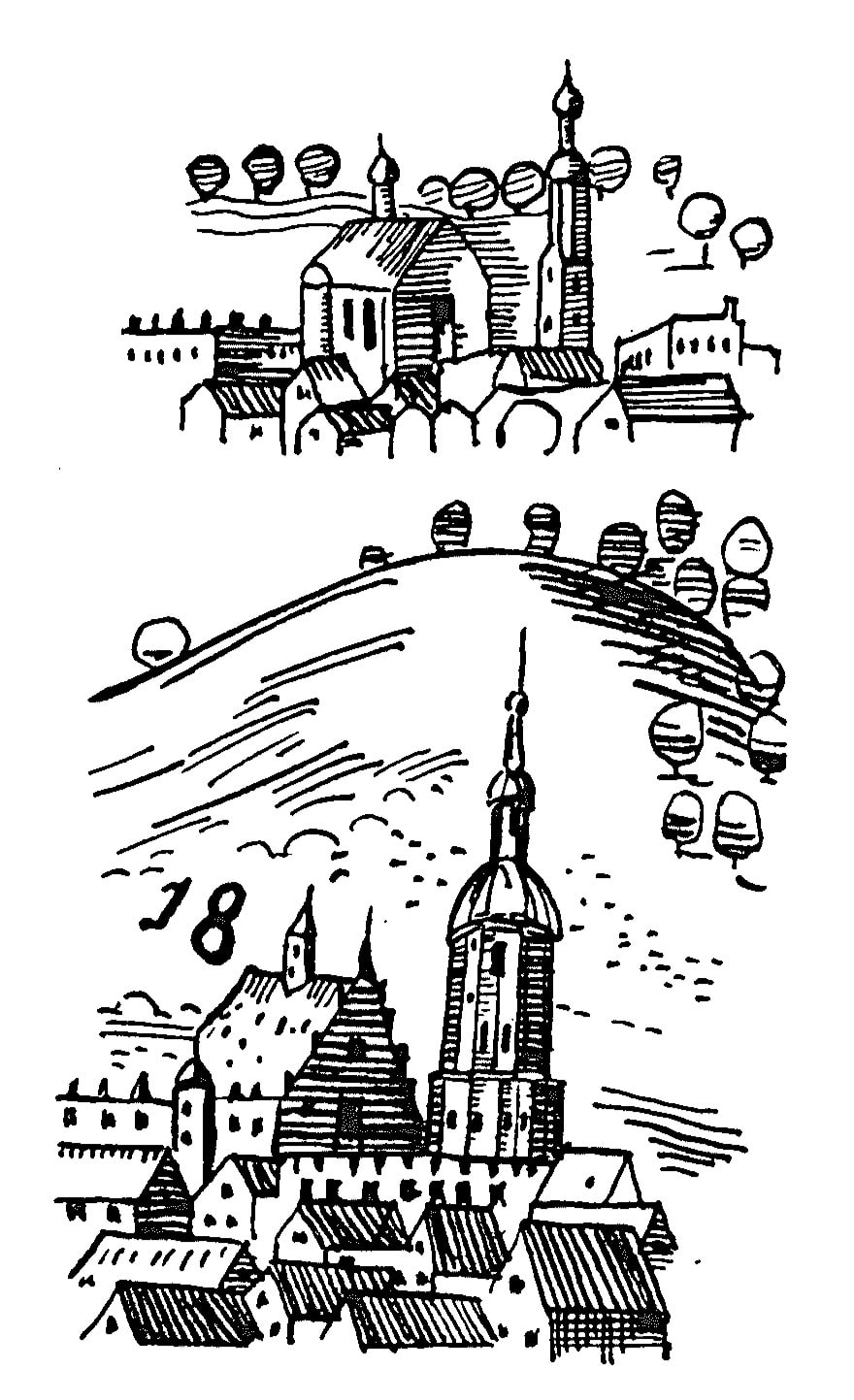

Holy Trinity Church is one of the oldest in Vilnius. They connect its appearance with the cult of the Orthodox saints Anthony, John, and Eustathius. These three courtiers of Grand Duke of Lithuania Algirdas in 1347 were martyred for their faith and, according to legend, on the very site where they perished the first shrine, a wooden church, was built in approximately 1374 (↑) (↑).1Darius Baronas, Trys Vilniaus kankiniai: gyvenimas ir istorija, Vilnius: Aidai, 2000, p. 93–94, 117–118. Later a monastery was founded near it; lay brotherhoods gathered here.2Auksė Kaladžinskaitė-Vičkienė, “XVI–XVIII a. Vilniaus amatininkų cechai ir jų altoriai”, Lietuvos katalikų mokslo akademijos metraštis, 2004, t. 24, p. 91. This all demonstrates its exceptional significance in the medieval city.

The next stage of the church’s history is marked by a donation in 1514 by Grand Hetman of Lithuania Konstanty Ostrogski. It is precisely at his initiative that a new brick, Gothic-style Holy Trinity Church arose. This was the duke’s thanksgiving to God for his victory over the Muscovites in the battle near Orsha (1514) [1, 2] (↑). In the 16th century, the church became the center of the cultural and religious life for the Ruthenians of Vilnius: a school, hospital, and printing press operated there, and in 1584 Holy Trinity Brotherhood was created, which united the members of previous lay brotherhoods.3Baronas Darius, “Stačiatikių Šv. Dvasios brolijos įsteigimas Vilniuje 1584–1633 m.”, Lietuvių katalikų mokslo akademijos metraštis, 2012, t. 36, p. 52.

The church union of 1596 (↑) was a fateful event for this shrine. After religious conflicts between Orthodox and Uniates at the turn of the 17th century, the church went to the Catholics of the Eastern rite. In 1617, the church was transformed into the spiritual center of the new Basilian Order and the whole Uniate Church. This renewal was connected with the names of St. Josaphat Kuntsevych (↑), who himself here began his own monastic life, and his colleague Josyf Veliamyn Rutsky (↑).

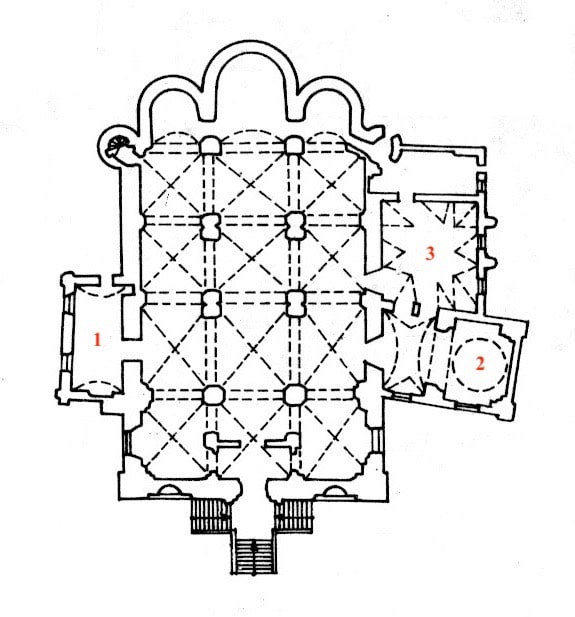

In the first half of the 17th century, a number of chapels with burial crypts were completed [3]. The wojski of the Polatsk voivodeship, Eustafi Korsak-Hołubicki, and his wife, Sofia, before 1622 funded the Chapel of St. Luke (at the northern side of the church) [4]. It was built before 1618, and in 1642 the voivode of Vilnius, Janusz Skumin-Tyszkiewicz rebuilt the Chapel of the Annunciation of the Most Holy Mother of God, which is often called simply the Chapel of the Skumins [5]. Nearby, a clerk of the territorial court, Jan Kolęda, in 1628 built the Chapel of the Exaltation of the True Cross with crypt [6] (↑).4Rūta Janonienė, “Architektūrinis ansamblis”, in: Vadimas Adadurovas, et al., Kultūrų kryžkelė. Vilniaus Švč. Trejybės šventovė ir vienuolynas, moksl. red. Alfredas Bumblauskas, Salvijus Kulevičius, Ihoris Skočiliasas, Vilnius: Vilniaus universiteto leidykla, 2017, p. 212–213; same: Рута Янонєнє, “Архітектурний ансамбль”, in: Вадим Ададуров, et al., На перехресті культур. Монастир і храм Пресвятої Трійці у Вільнюсі (series: Київське християнство, т. 16), наук. ред. Альфредас Бумблаускас, Сальвіюс Кулявічюс, Ігор Скочиляс, Львів: Український католицький університет, 2019, с. 311–330. Through the 17th and 18th centuries, the number of side altars in the church grew, and they were taken care of by the Uniate religious brotherhoods of the Holy Trinity, the Immaculate Conception of the Most Holy Mother of God, and of St. Onuphrius (↑).5When the previously-established Orthodox Holy Trinity Brotherhood transferred to Holy Spirit Church in Vilnius, at the Uniate Holy Trinity Church Metropolitan Hipacy Pociej created a Uniate brotherhood of the same name. The Brotherhood of the Immaculate Conception of the Most Holy Mother of God operated from the middle of the 17th century. Records of the St. Onufriy Brotherhood begin in 1716.

During the fire of 1706, almost all the interior decoration of the church was destroyed, but only a few years later here again stood many decorated wooden altars. A few of them were created by a master of the Vilnius carpenters’ guild, Friedrich Kwieczor. In 1785, the church had 11 wooden altars.6Rūta Janonienė, op. cit., p. 214; same: с. 316 One of the most important was the altar of the Most Holy Mother of God with the wonder-working icon of the Mother of God Hodigitria [7]. It came to this church at the start of the 17th century, but earlier was at Dormition Cathedral in Vilnius.7Duchess Elena, betrothed to Lithuanian Grand Duke Alexander, who married him in 1494 brought the icon to Vilnius from Moscow. At the end of the century, the burgomaster of the city, Jerzy Pawłowicz funded a luxuriously decorated altar to “exhibit” the icon. In his testament he also allotted expenses to encourage the cult of this image.8Rūta Janonienė, op. cit., p. 213; same: с. 213. From the second half of the 17th century, the altar of Josaphat Kuntsevych, beatified in 1642, would attract the faithful. The burgomaster of Vilnius, Jan Ohurcewicz, in his testament of 1687 gave generous support to the Basilian monks, obligating them every week to celebrate two Divine Liturgies near the altar of Josaphat.9Ibid.

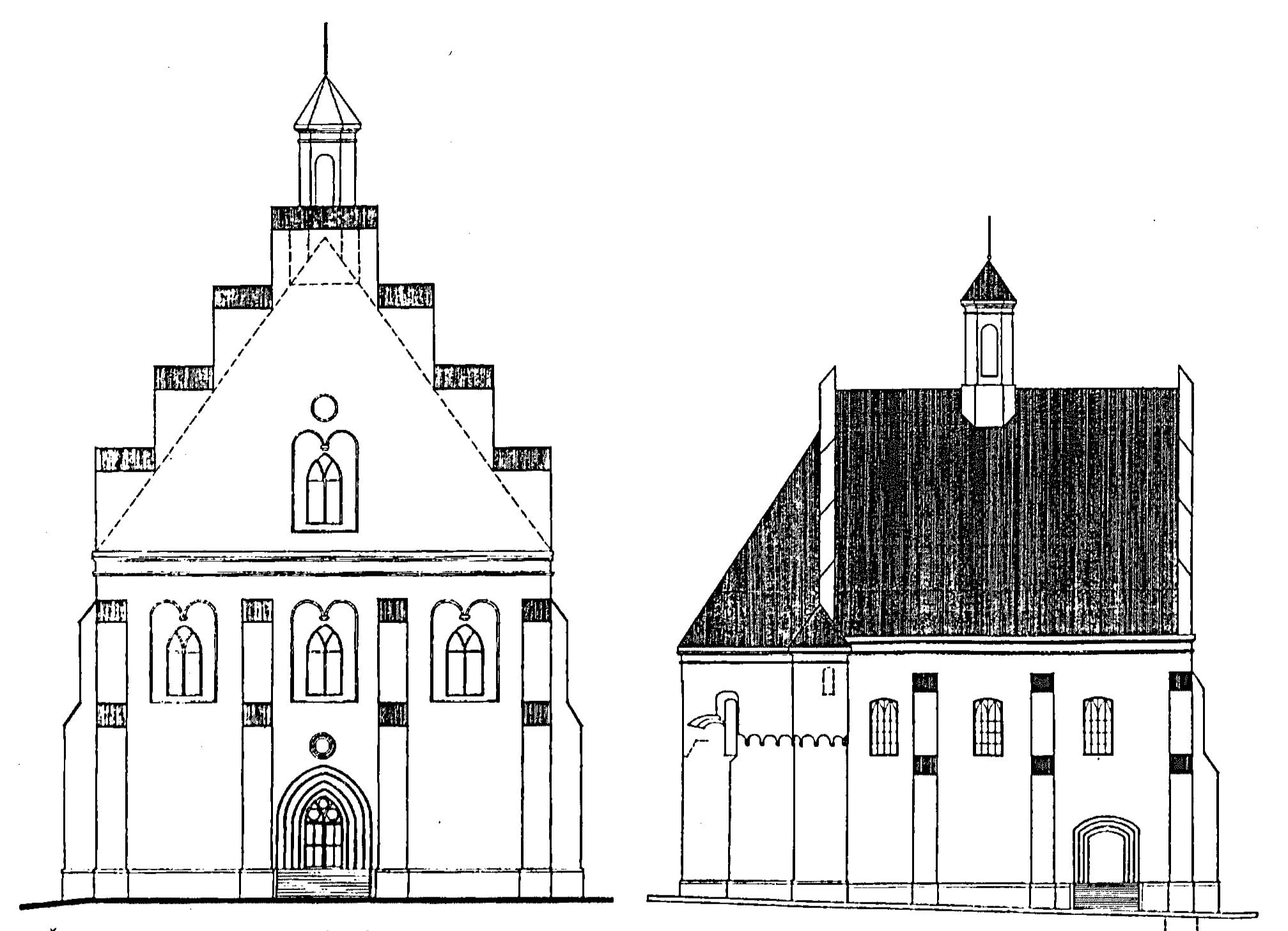

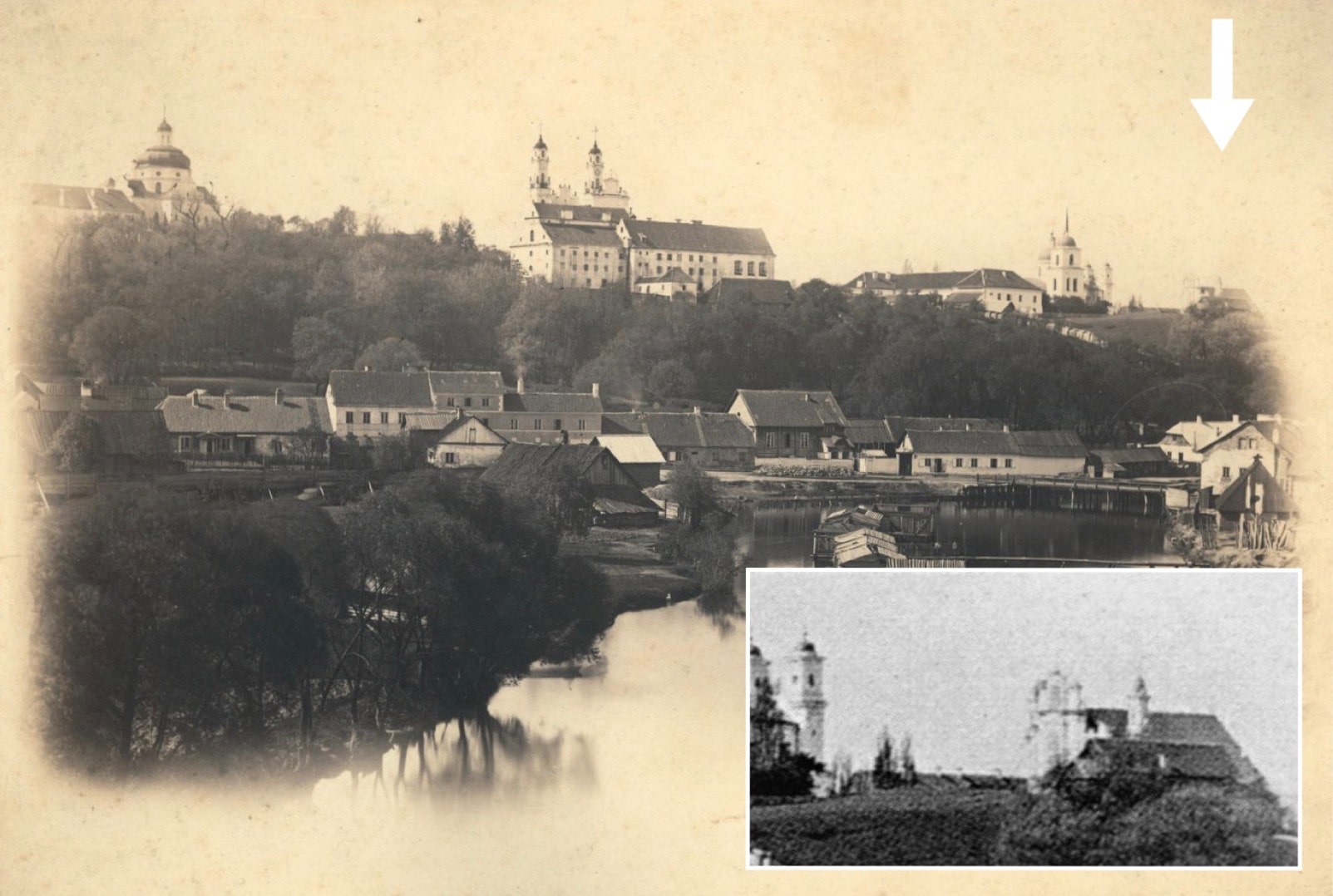

During the repair of the church after the previously-mentioned fire, some of its external appearance was changed: perhaps that was when they dismantled the buttresses and plastered the outside walls. After 1761, according to the project of architect Johann Christoph Glaubitz the back (eastern) façade of the church underwent reconstruction: the gable was rebuilt; it was given the characteristics of late baroque; the side towers were raised and new stairs, with baroque forms, were made from them. This façade towered over the buildings, which were constructed around the church and obscured it, and it is best visible from the street side (today these are Didžioji and Aušros Vartų streets), and also from the side of the yard of the main opponent, Holy Trinity Orthodox Church. As we see, from such a perspective, it played a representative role, and baroque was chosen for this representation. With such a “manifestation”, the Uniate church greeted guests [8, 9, 10].

Later, reconstructions were done at an even greater scale. Before 1792, the main (western) façade was taken down and the church was continued in the western direction. In this way its space was more like the space of three-nave Roman Catholic churches.10See more: Rūta Janonienė, op. cit., p. 215–217; same: с. 317–320. In the new part of the church, an organ choir loft was built and an organ installed. Now the altar ensemble was composed of nine altars: the great one, in the central apse; six of brick – near the pillars; two more with brick mensa (altar table) and “optically” (with the technique of illusory painting) painted retables – in the side apses. The altars were adapted for both Eastern and Latin liturgies. In the cimborium of the great altar (in two gilded tabernacles) the Holy Gifts are preserved for the celebration of services, regardless of rite. Although earlier the Holy Gifts for the Liturgy in the Eastern rite were preserved in the altar of the Most Holy Mother of God, for that in the Latin rite they were in the cimborium of the great altar. Before the great altar a portable, wooden half-spherical classical iconostas stood. (It was easy to disassemble when a Mass was celebrated.) Similarly as in Roman Catholic monastery churches, the monastery choirs were in back. Of the old icons, images of the Mother of God and Blessed Josaphat Kuntsevych were transferred to the new altars. Both had beautiful frames. Franciszek Smuglewicz painted six icons for these altars.11LMAVB, Rankraščių skyrius, f. 41–81, l. 3.

The changes that happened at the end of the 18th century also touched the chapels of the church: the one dedicated to St. Luke was transformed into a chapel for confession and communion for the Basilian nuns, and, in place of the Chapel of the Exaltation of the True Cross, they installed a sacristy, joined to the monastery with a new brick corridor (↑).12Rūta Janonienė, op. cit., p. 218, 219; same: с. 323–324.

In the 19th century, tendencies to reconstruct the church took an entirely different direction: if to this point the goal was to strengthen and emphasize the Uniate tradition, now above all the goal was the destruction of the Uniate legacy (↑). These transformations began already in 1834–1835 at the orders of Metropolitan Józef Siemaszko.13See more: Rūta Janonienė, op. cit., p. 219–223; same: с. 324–330. This tendency became even stronger after 1839, when the ensemble was given to the Orthodox. A new iconostas was prepared in 1850–1851. Ivan Khrutsky executed part of the images for it [11, 12, 13].14See more: Lietuvos dailininkų žodynas, t. 2: 1795–1918 m., sud. Jolanta Širkaitė, Vilnius: Lietuvos kultūros tyrimų institutas, 2012, p. 305–306. The church, renewed in this way, was consecrated on 4 November 1851.15LVIA, f. 1178, ap. 1, b. 132, l. 10. In 1851–1852, after completing a great amount of work, the Chapel of the Skumins was rebuilt as the Chapel of St. John the Theologian with an altar and iconostas in the Eastern tradition.

In 1868, according to the project of architect Nikolai Chagin, the roof of the church was lowered and a cupola was put on it (or more like a wooden imitation of one) [14, 15, 16]. The main (western) façade was also reconstructed; it was given the features of neo-Byzantine architecture. The shrine changed its appearance a few more times at the end of the 19th century. For example, in 1891 the Chapel of St. John the Theologian was rebuilt and expanded; it was joined with the former sacristy and corridor that led to the monastery [17, 18] (↑) (↑).16Ibid., b. 221, l. 95–102, 107.

In the first half of the 20th century, Holy Trinity Church was given to the Catholic Society of St. Vincent De Paul, the wooden cupola was taken off its roof, and other remodeling work was done. In 1992–1994, the church was returned to the community of the Greek-Catholics of Lithuania, its restoration was begun, and a new iconostas was installed (↑).

Rūta Janonienė

Išnašos:

| 1. | ↑ | Darius Baronas, Trys Vilniaus kankiniai: gyvenimas ir istorija, Vilnius: Aidai, 2000, p. 93–94, 117–118. |

|---|---|---|

| 2. | ↑ | Auksė Kaladžinskaitė-Vičkienė, “XVI–XVIII a. Vilniaus amatininkų cechai ir jų altoriai”, Lietuvos katalikų mokslo akademijos metraštis, 2004, t. 24, p. 91. |

| 3. | ↑ | Baronas Darius, “Stačiatikių Šv. Dvasios brolijos įsteigimas Vilniuje 1584–1633 m.”, Lietuvių katalikų mokslo akademijos metraštis, 2012, t. 36, p. 52. |

| 4. | ↑ | Rūta Janonienė, “Architektūrinis ansamblis”, in: Vadimas Adadurovas, et al., Kultūrų kryžkelė. Vilniaus Švč. Trejybės šventovė ir vienuolynas, moksl. red. Alfredas Bumblauskas, Salvijus Kulevičius, Ihoris Skočiliasas, Vilnius: Vilniaus universiteto leidykla, 2017, p. 212–213; same: Рута Янонєнє, “Архітектурний ансамбль”, in: Вадим Ададуров, et al., На перехресті культур. Монастир і храм Пресвятої Трійці у Вільнюсі (series: Київське християнство, т. 16), наук. ред. Альфредас Бумблаускас, Сальвіюс Кулявічюс, Ігор Скочиляс, Львів: Український католицький університет, 2019, с. 311–330. |

| 5. | ↑ | When the previously-established Orthodox Holy Trinity Brotherhood transferred to Holy Spirit Church in Vilnius, at the Uniate Holy Trinity Church Metropolitan Hipacy Pociej created a Uniate brotherhood of the same name. The Brotherhood of the Immaculate Conception of the Most Holy Mother of God operated from the middle of the 17th century. Records of the St. Onufriy Brotherhood begin in 1716. |

| 6. | ↑ | Rūta Janonienė, op. cit., p. 214; same: с. 316 |

| 7. | ↑ | Duchess Elena, betrothed to Lithuanian Grand Duke Alexander, who married him in 1494 brought the icon to Vilnius from Moscow. |

| 8. | ↑ | Rūta Janonienė, op. cit., p. 213; same: с. 213. |

| 9. | ↑ | Ibid. |

| 10. | ↑ | See more: Rūta Janonienė, op. cit., p. 215–217; same: с. 317–320. |

| 11. | ↑ | LMAVB, Rankraščių skyrius, f. 41–81, l. 3. |

| 12. | ↑ | Rūta Janonienė, op. cit., p. 218, 219; same: с. 323–324. |

| 13. | ↑ | See more: Rūta Janonienė, op. cit., p. 219–223; same: с. 324–330. |

| 14. | ↑ | See more: Lietuvos dailininkų žodynas, t. 2: 1795–1918 m., sud. Jolanta Širkaitė, Vilnius: Lietuvos kultūros tyrimų institutas, 2012, p. 305–306. |

| 15. | ↑ | LVIA, f. 1178, ap. 1, b. 132, l. 10. |

| 16. | ↑ | Ibid., b. 221, l. 95–102, 107. |

Sources of illustrations:

| 1. | Published in: Algė Jankevičienė, „Dviejų stilių sintezė XVI a. Vilniaus cerkvių architektūroje“, in: Lietuvos Didžiosios Kunigaikštystės gotika: sakralinė architektūra ir dailė (series: Acta Academiae Artium Vilnensis = Vilniaus dailės akademijos darbai. Dailė, t. 26), sud., red. Algė Jankevičienė, Vilnius: Vilniaus dailės akademija, 2002, p. 172 (il. 12). |

| 2. | Held in: VRVA, f. 1019, ap. 12, b. 24275, l. 81, 82. Published in: Algė Jankevičienė, op. cit., p. 172 (il. 13–14). |

| 3. | Published in: Vytautas Levandauskas, „Šventosios Trejybės cerkvės ir bazilijonų vienuolyno ansamblis“, in: Lietuvos TSR istorijos ir kultūros paminklų sąvadas, t. 1: Vilnius, Vilnius: Vyriausioji enciklopedijų leidykla, 1988, p. 236 (il. 156). |

| 4. | Private collection of Salvijus Kulevičius. |

| 5. | Ibid. |

| 6. | Ibid. |

| 7. | Held in: MNW, 145073/170 MNW (Available at: Cyfrowe zbiory Muzeum Narodowego w Warszawie, https://cyfrowe.mnw.art.pl/pl/katalog/709783, accessed: 2021 12 01). See also: Rūta Janonienė, „Vilniaus Dievo Motinos ikona ir jos kultas Švč. Trejybės cerkvėje“, Menotyra, 2017, t. 24, nr. 1, p. 1–16.. |

| 8. | Held in: VUB, Grafikos kabinetas, PeszJ IID-1 (Available at: Vilniaus universiteto biblioteka. Skaitmeninės kolekcijos, https://kolekcijos.biblioteka.vu.lt/islandora/object/kolekcijos%3AVUB06_000001936, accessed: 2021 12 01) |

| 9. | Held in: MNW, DI 37947 MNW (Available at: Cyfrowe zbiory Muzeum Narodowego w Warszawie, https://cyfrowe.mnw.art.pl/pl/katalog/952147, accessed: 2021 12 01). |

| 10. | Held in: LNDM, LNDM Fi 1 (Available at: Lietuvos integrali muziejų informacinė sistema, www.limis.lt/greita-paieska/perziura/-/exhibit/preview/20000004123691?s_id=HTSzf6xM3Q8jFqzi&s_ind=8&valuable_type=EKSPONATAS, accessed: 2021 12 01). |

| 11. | Held in: VRVA, f. 1019, ap. 11, b. 5214, l. 37. Published in: „Religinių konfesijų įvairovė ir jų sakralinių pastatų architektūra archyvo dokumentuose“, in: Virtualios parodos. Archyvai, 2020, available at: https://virtualios-parodos.archyvai.lt/lt/virtualios-parodos/34/religiniu-konfesiju-ivairove-ir-ju-sakraliniu-pastatu-architektura-archyvo-dokumentuose/exh-190/religiniu-konfesiju-ivairove-ir-ju-sakraliniu-pastatu-architektura-archyvo-dokumentuose/case-945, accessed: 2021 12 01; „Vilniaus bazilijonų vienuolyno statinių ansamblis“ [unique code: 681], in: Kultūros vertybių registras, available at: https://kvr.kpd.lt/#/static-heritage-detail/06cabf58-1daa-4641-af11-c7de1aa4f2c5, photo no. 36, accessed: 2021 12 011. |

| 12. | Published in: А. А. Виноградов, Православная Вильна, 1904, Вильна: тип. Штаба Вилен. воен. окр., p. 25; А. А. Виноградов, Путеводитель по городу Вильне и его окрестностям, 1904, Вильна: тип. Штаба Вилен. воен. окр., p. 67; „Vilniaus bazilijonų vienuolyno statinių ansamblis…“, photo no. 37, accessed: 2021 12 01. |

| 13. | Published in: А. А. Виноградов, Православная Вильна…, p. 22; А. А. Виноградов, Путеводитель по городу Вильне…, p. 64. |

| 14. | Памятники русской старины в западных губерниях империи, t. 5: Вильна: [album], Санктпетербург: [М-во внутр. дел], 1870, il. 12. Held in: LNDM, LNDM G 804/9 (Available at: Lietuvos integrali muziejų informacinė sistema, www.limis.lt/greita-paieska/perziura/-/exhibit/preview/20000006367804, accessed: 2021 12 01). |

| 15. | [Vilnius: Photo studio of J. Bułhak], [1913–1915]. Held in: LMAVB, Retų spaudinių skyrius, SFg-2403/2/1. Published in: „Vilniaus stačiatikių vienuolynas ir Šv. Dvasios cerkvė bei Švenčiausiosios Trejybės bažnyčia ir buvęs Bazilijonų vienuolynas“, in: Lietuvos mokslų akademijos Vrublevskių biblioteka. Skaitmeninis archyvas (Available at: http://elibrary.mab.lt/handle/1/6248, accessed: 2021 12 01). |

| 16. | Вильна. Свято-Троицкий Монастырь: [Postcard], Wilna: A. Fialko, 1903. Held in: LMAVB, Retų spaudinių skyrius, Atv-103/956 (Available at: „Bibliotekos katalogas“, in: Lietuvos mokslų akademijos Vrublevskių biblioteka, https://aleph.library.lt/F?func=direct&local_base=MAB01&doc_number=000281276, accessed: 2021 12 01). |

| 17. | Held in: LVIA, f. 1178, ap. 1, b. 105, l. 109. Published in: „Vilniaus bazilijonų vienuolyno statinių ansamblis…“, photo no. 16, accessed: 2021 12 01. |

| 18. | A. Samukienė, R. Racevičius, I. Bilytė, J. Kalmantienė, A. Knyva, Buv. vienuolyno pastatų ansamblis Vilniuje, Gorkio g. 73. Buv. Švč. Trejybės cerkvė ir varpinė. Architektūriniai tyrimai, 1984. Held in: KPC PB, f. 5, ap. 2, b. 2314, l. AS-8. Published in: „Vilniaus bazilijonų vienuolyno statinių ansamblis…“, no. 16, accessed: 2021 12 01. See also: Vilda Jakštaitė, Vilniaus bazilijonų vienuolyno Švč. Trejybės cerkvės ir varpinės istorinė–architektūrinė raida: [summary of master’s work], Vilnius: Vilniaus dailės akademija, 2017, p. 79. Published in: Lietuvos akademinė elektroninė biblioteka [eLABa ID: 22904495], available at: www.lvb.lt/primo-explore/fulldisplay?docid=ELABAETD22904495&context=L&vid=ELABA&lang=lt_LT&search_scope=eLABa&adaptor=Local%20Search%20Engine&tab=default_tab&query=any,contains,Vilniaus%20bazilijonų%20vienuolyno%20Švč.%20Trejybės%20cerkvės%20ir%20varpinės%20istorinė%20–%20architektūrinė%20raida&offset=0, accessed: 2021 12 01. |