The Union of Brest of 1596 was an act of separation from the Patriarchate of Constantinople and uniting part of the Ruthenian (Ukrainian-Belarusian) Orthodox Church with the Roman Catholic Church in the area of the Kyivan Metropolitanate, which functioned on the territory of the Commonwealth. The religious community which arose as a consequence of uniting with Rome began to be called the Uniate Church (from the start of the 19th century, the Greek-Catholic Church, and in independent Ukraine, the Ukrainian Greek-Catholic Church).

A number of factors influenced the historical pre-conditions for the Union of Brest: the propagation of the idea of union by post-Tridentine Catholicism, the active missionary efforts of the Jesuits in Eastern Europe, the failure of the attempts of Rome to convert Orthodox Muscovy to Catholicism in the 1580s, the unequal standing of Orthodoxy in the Commonwealth compared with the dominant Catholic Church, crises in the ecclesiastical life of the Kyivan Metropolitanate, changes in religious culture in the second half of the 16th century, which witness to a confessional-cultural openness to influences of the West, the interference of Patriarch of Constantinople Jeremiah II in the affairs of the metropolitanate in 1588–1589, programs of church reforms from the 1580s to the first half of the 1590s and unsuccessful attempts to end them, the conflict of church brotherhoods with the episcopate and conflicts among the hierarchs, and a favorable international political situation at the end of the century.1Леонід Тимошенко, “Берестейська церковна унія 1596 року”, Наукове товариство імені Шевченка. Енциклопедія, т. 1, Київ, Львів, Тернопіль: Наукове товариство ім. Шевченка, Інститут енциклопедичних досліджень НАН України, 2012, с. 521–522. As a result of these factors, the union initiative of the episcopate of the Kyivan Metropolitanate arose.

The process that led to the signing of the Union had not only many stages but also many facets. In the 1570s–1580s, the Union idea was actively propagated by Jesuit Piotr Skarga, who taught at the Vilnius University and preached at the city’s cathedral (the work “On the unity of God’s Church under one pastor”, 1577). And so Vilnius became a center for the spread of the Union idea. Here in the printing press of the Mamonicz in 1595, the book “Union” by Bishop Hipatius Pociej of Volodymyr-Brest (↑) was published. He and Bishop Cyril Terlecki of Lutsk-Ostrih became leaders of the Union initiative. The transfer of Metropolitan Michael Rohoza to the Uniate camp was very late (December 1594). The Union program of the hierarchy of the Ruthenian church was set forth in the document “33 articles of Union”, which was directed to Rome. The advisability of union was demonstrated by the need to liquidate the schism of Christianity, the danger of the spread of heresies, and also the captivity of patriarchs under pagans. Characteristic of the articles was a desire to limit the patronal rights of the Polish kings and to strengthen internal church discipline based on the example of the Catholic Church, especially episcopal administrative and canonical authority.2Леонід Тимошенко, Берестейська унія 1596 р., Дрогобич: Коло, 2004, с. 11–14. The program for a regional union of the Ruthenian Church was different from the plans for universal union of Duke Konstanty Wasyl Ostrogski and the program for reforms of Orthodox church brotherhoods.

At the end of 1595 in Rome, where a delegation of the Ruthenian Church including bishops Pociej and Terlecki had come, articles were submitted for the close analysis of theological experts. An important stage of the union process was ceremonies in Rome on 23 December 1595, when bishops Pociej and Terlecki at a celebratory ceremony with Pope Clement VII accepted the Catholic confession of faith. The bulls of Pope Clement VIII “Magnus Dominus” (23 December 1595) and “Decet Romanum Pontificem” (23 February 1596) were also considered decisive for the fate of the Union (23 February 1596).3Основні документи Берестейської унії (series: Наукові зошити, т. 2), Львів: Видавничий відділ „Свічадо“, 1996, с. 65–80. These and other Roman documents established the jurisdictional status of the Ruthenian Church under the patronage of the Apostolic See.

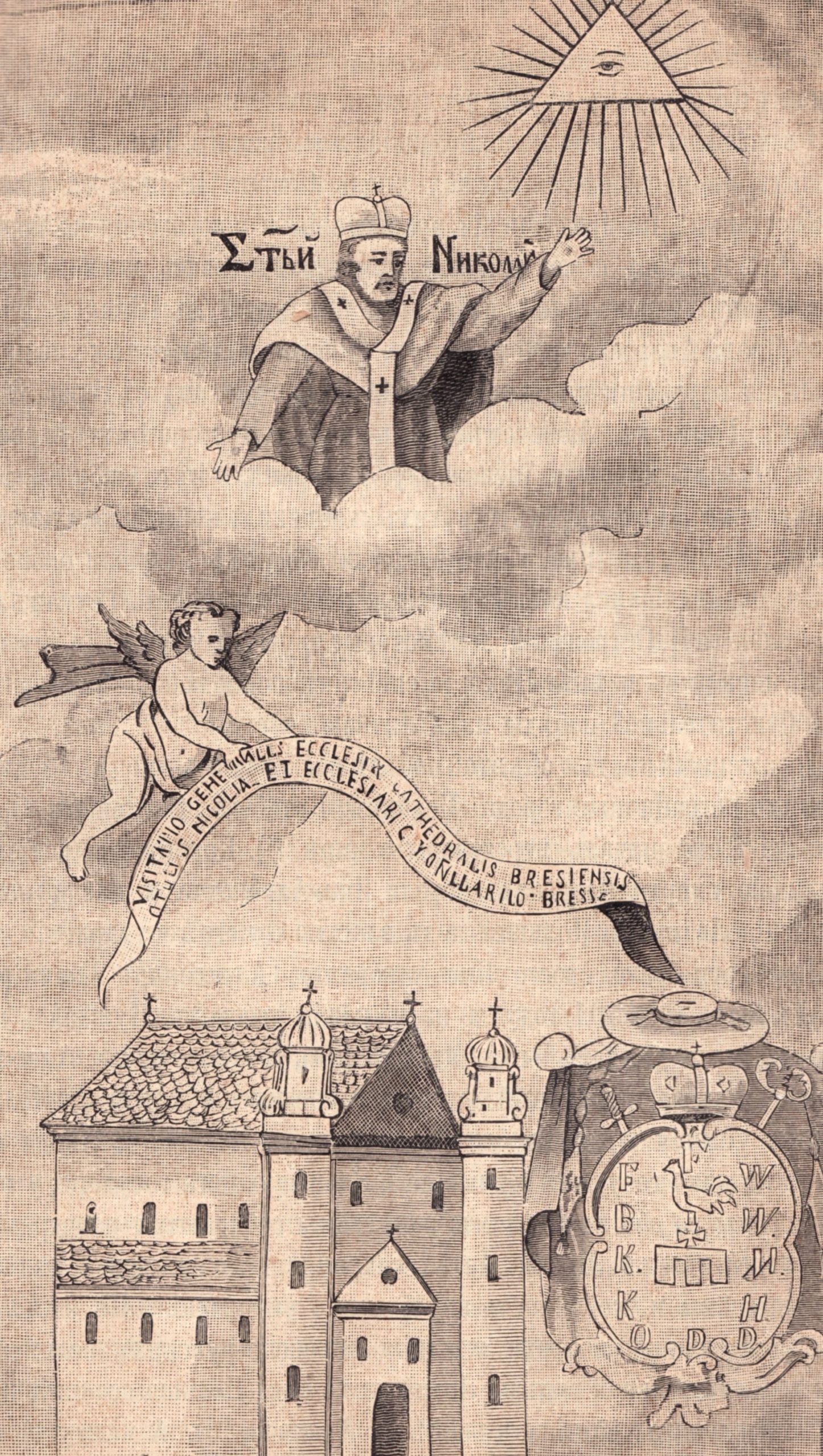

The declaration of union happened at the union council in Brest-Litovsk in October 1596. Not coming to a mutual understanding, the Uniate and Orthodox parties on 8 October started to hold separate councils: the Uniates in the city’s Church of St. Nicholas [1] and the Orthodox in the house of Rajski, where Duke Ostrogski had stopped. A joint council, which would have united supporters and opponents of union, did not happen. All the participants of the councils of Brest, noted in the sources, number 175 people: 24 participants of the Uniate and 151 participants of the Orthodox.4Леонід Тимошенко, Берестейська унія…., с. 35.

There were nine hierarchs at the union council: Metropolitan of Kyiv, bishops of Vladimir-Brest, Lutsk-Ostroh, Polotsk, Pinsk-Turov, and Chelm. Also participating in the council were archimandrites of Minsk, Braslaw, and Lavrishiv. There were also nine Roman Catholics: three bishops (of Lutsk, Lviv, and Cholm); four Jesuits, and two Greeks from Rome. The secular part of the council was small, totaling six people: voivode of Vilnius Mikołaj Krzysztof Radziwiłł, GDL Chancellor Lew Sapieha, starosta of Brest Chalecki, castellan of Kamianets-Podilskyi, Duke Shuisky, and instigator Kalinski. This part of the council represented the most influential Latinized magnates of the GDL.5Ibid., с. 177–178.

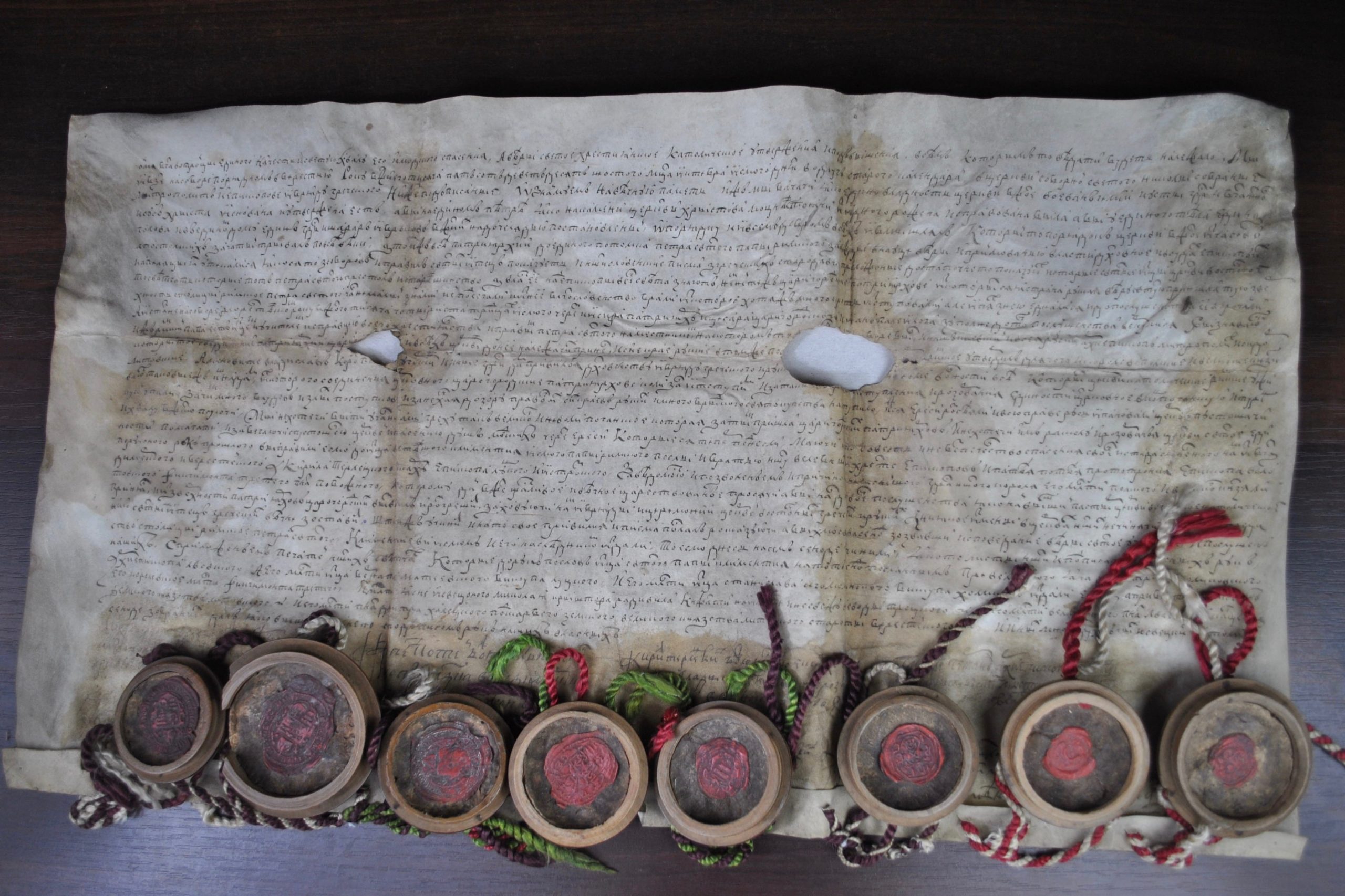

Under the leadership of Kyiv Metropolitan Michael Rohoza, the council on 8 October accepted the declaration (charter) about the transfer to the Union, the main document, which is based on the declarative recognition of the Florentine idea of the unity of the Churches [2]. In it, the center of attention is the grounding of motives for union. The document is a declaration of the ceremonial proclamation of union, so it is filled with the pathos of piety and the holiness of what has been done, and also responsibility before God for human fates.

There were many more participants in the parallel Orthodox council (religious numbered 74 and seculars 77). Seven representatives of Eastern Orthodox Churches were among the religious.6Ibid., с. 35.

After the councils of Brest, interconfessional conflict exploded, with Vilnius as the center. Vilnius had not delegated a single representative for the Uniate council in Brest, though at the Orthodox council their delegation was very representative (seven religious: ambassadors from the Vilnius chapter: three priests; two Fathers of the Vilnius brotherhoods; and also two monks of Holy Spirit Monastery in Vilnius); and preacher from Holy Trinity Monastery in Vilnius. The secular delegation was also large (12 people, generally famous members of brotherhoods) (↑) (↑) (↑).7Леонід Тимошенко, Руська релігійна культура Вільна. Контекст доби. Осередки. Література та книжність (XVІ – перша третина XVII ст.), Дрогобич: Коло, 2020, с. 355–356. After 1596, religious polemic heated up, and Vilnius was also the center. In 1597, here a number of weighty works in defence of union were published: “A description and defense of the Ruthenian council of Brest” of Skarga, and “A just description of the acts and matters of the synod…” of Pociej. In 1600, Pociej work “Antiresis” was published. The Orthodox responded with the work “Apokrisis” (1597, press of the brotherhood).8Ibid., с. 403–429.

The center of the Orthodox in Vilnius already in 1597 was Holy Spirit Monastery; the center of the Uniates was Holy Trinity Monastery.

The councils of Brest, which showed the division of the Christianity of Kyivan-Rus (in fact, two parallel Kyivan metropolitanates existed), started the conflict of Rus with Rus, at the basis of which were the problems of the formation of the Kyivan Church. And so ethnic-confessional awareness grew, which influenced the legitimation of the holy right of the Cossack uprising against the Commonwealth. The Orthodox Council of Brest of 1596 rescued, without a doubt, Ukrainian-Belarusian Orthodoxy, which flowered in the epoch of Peter Mogila. The Uniate council started a religious-ecclesiastical tradition which was oriented to a western model (↑).

Leonid Tymoshenko

Išnašos:

| 1. | ↑ | Леонід Тимошенко, “Берестейська церковна унія 1596 року”, Наукове товариство імені Шевченка. Енциклопедія, т. 1, Київ, Львів, Тернопіль: Наукове товариство ім. Шевченка, Інститут енциклопедичних досліджень НАН України, 2012, с. 521–522. |

|---|---|---|

| 2. | ↑ | Леонід Тимошенко, Берестейська унія 1596 р., Дрогобич: Коло, 2004, с. 11–14. |

| 3. | ↑ | Основні документи Берестейської унії (series: Наукові зошити, т. 2), Львів: Видавничий відділ „Свічадо“, 1996, с. 65–80. |

| 4. | ↑ | Леонід Тимошенко, Берестейська унія…., с. 35. |

| 5. | ↑ | Ibid., с. 177–178. |

| 6. | ↑ | Ibid., с. 35. |

| 7. | ↑ | Леонід Тимошенко, Руська релігійна культура Вільна. Контекст доби. Осередки. Література та книжність (XVІ – перша третина XVII ст.), Дрогобич: Коло, 2020, с. 355–356. |

| 8. | ↑ | Ibid., с. 403–429. |

Sources of illustrations:

| 1. | Published in: Помпей Николаевич Батюшков, Белоруссия и Литва. Исторические судьбы Северо-Западного края, Санкт-Петербург: „Общественная польза”, 1890, p. 141. |

| 2. | Held in: ЦДІАЛ України, ф. 131, оп. 1, спр. 627. Published in: Czterechsetlecie zawarcia Unii Brzeskiej, 1596–1996, red. Stanisław Alexandrowicz, Tomasz Kempa, Toruń: Towarzysto Naukowe w Toruniu, 1998 (insert between pages 10 and 11). |