Circumstances

After the first division of the Commonwealth (1772), the Polotsk Archeparchy came under Russian jurisdiction, after the second (1793) Lutsk, and after the third (1795) the Vilnius and Brest eparchies. In 1815, the Cholm Eparchy also came under Russia. The two periods of the existence of the Greek-Uniate Church and confession – early imperial (1772–1830) and later imperial (1832–1875) – are separated by the Polish uprising of 1830–1831. Its defeat marked the transition from a hybrid policy of habituation and cooperation, relatively soft, in the spirit of the ideas of the Enlightenment, though not lacking in excesses and extremes, to brutal religious conversion according to the model “one rite, one Church”. The latter was implemented by emperors Nicholas I (1825–1855) and Alexander II (1855–1881) according to the ideology of Russian imperial nationalism.

Through the first period, relations between the Russian administration and the 1.4 million Uniates settled on the western peripheries of the empire balanced on the edge of an insecure compromise. The last three years of the reign of Empress Catherine II (1762–1796) were an exception to the general rule, marked (against the background of the second and third divisions of the Commonwealth and the uprising under the leadership of Tadeusz Kościuszko) by administrative and military terror against the Uniates, who lost in the Polotsk Archeparchy three monasteries and more than 100 parish churches out of a total of 400.1Поділ Київської та піднесення Галицької унійних митрополій: документи та матеріали ватиканських архівів 1802–1808 рр. (series: Київське християнство, т. 19), упор. Вадим Ададуров, Львів: Видавництво Українського католицького університету, с. 88. Under the rule of emperors Paul I (1796–1801) and Alexander I (1801–1825), the Greek-Uniate Church managed to make up for the majority of losses of the previous time: it numbered 1681 pastors, 768 monks, 87 nuns, and possessed approximately 1500 church buildings.2Bolesław Kumor, Historia Kościoła, cz. 7: Czasy najnowsze 1815–1914, Lublin: KUL, 1991, s. 101.

The three historical generations, which changed every 20 years between 1772 and 1832, underline three stages of the habituation of the Uniates to the imperial context: from co-existence with the Russian regime forced by circumstances (the first generation in fact continued to be guided by the thinking of the social culture of the Commonwealth, suffering changes in the borders of ecclesiastical provinces and the breaking of traditional connections);3Larry Wolff, “The Uniate Church and the partitions of Poland: Religious Survival in an Age of Enlightened Absolutism”, Harvard Ukrainian Studies, 2002–2003, vol. 26, no. 1/4, p. 153–244. to a game by new rules (the second generation after the liquidation of the Commonwealth between 1795 and 1812 gradually lost its illusions of the possibility of returning to the past – it was at this time that the emperor’s order of 24 July 1806 divided the Kyivan Uniate Metropolitanate and replaced it with “a metropolitanate for all Uniate Churches in Russia”);4Поділ Київської…, с. 78. and, finally, to gradually forgetting the experience of the Commonwealth (the third generation, which was born after the divisions of the Polish-Lithuanian state). After 1815, the following sociocultural phenomena spread: use of the Russian language parallel with Polish in ecclesiastical documentation; the participation of priests in the activities of government institutions (for example, schools and courts, and in 1805 a separate department for Uniates at the Roman Catholic College at the College of Justice);5Фундація Галицької митрополії у світлі дипломатичного листування Австрії та Святого Престолу 1807–1808 років: Збірник документів, вступна стаття та коментарі Вадим Ададуров, Львів: Видавництво Українського католицького університету, 2011, с. XXXVI. and the formation of an ecclesiastical hierarchy not only in internal vocational schools and seminaries but also at imperial universities (↑). At this time, the Uniate clergy became a hybrid component of the colonial system in western provinces, part of which, especially in the Polotsk Archeparchy, remained loyal to Russia, even during the French occupation of 1812. This included monks in the city of Tolochyn, like Archbishop of Polotsk Jan Krasowski, who managed to flee, though in the Vilnius and Lutsk eparchies a part of the clergy (for example, Auxiliary Bishop Adrian Holownia and the Basilian hegumen in Volodymyr-Volynskyi Januarij Bystrij, supported Emperor Napoleon I (1769–1821)).6Вадим Ададуров, Социокультурная история русского похода Наполеона, т. 1: Религия–язык, Киев: Лаурус, 2017, с. 234–235. Also, a number of secular priests took advantage of French rule so that church buildings and parishes which had earlier been given over to Orthodoxy would be returned to them. However, the practice of pastors naming their children “Napoleon”, a practice hostile to Russia, did not gain significant popularity.7Дзяніс Лісейчыкаӯ, Святар у беларускім соцыуме: Прасапаграфія беларускаго ӯніяцкага духовенства 1596–1839, Мінск: Нацыянальны гістарычны архів Беларусі, 2015, с. 27, 80–81. In general, Uniates made their political choices in 1812 not based on confession but on personal motives.

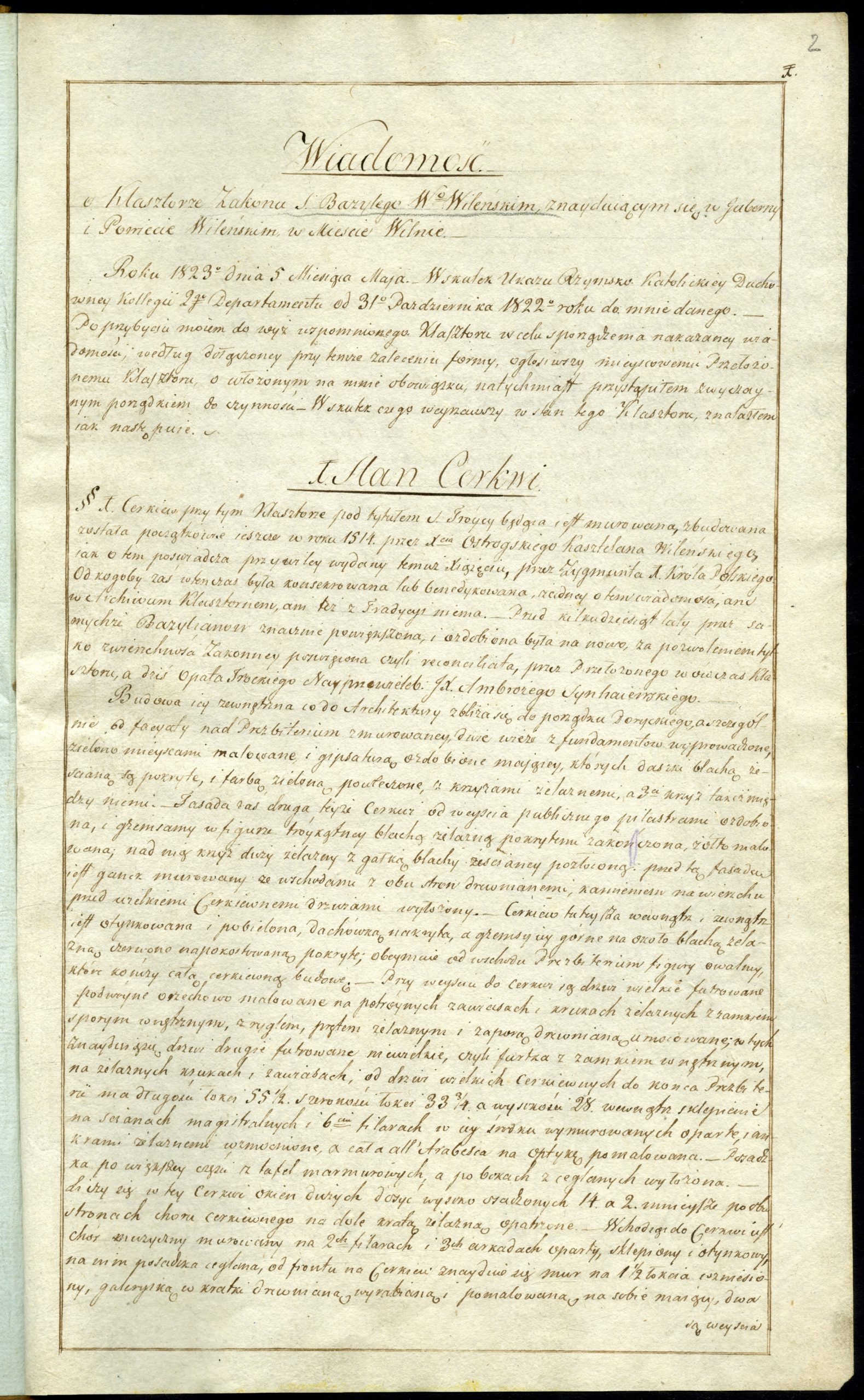

Despite the clear tendency of reducing the number of monasteries and their inhabitants (the periodic closing of the smallest and the confiscation of land holdings),8Marian Radwan, “Bazylianie w zaborze rosyjskim w latach 1795–1839”, Nasza Przeszłość, 2000, t. 93, s. 220–222. the attitude of the Russian government to the Order of St. Basil the Great was more liberal than in those parts of the former Commonwealth which ended up under Austrian and Prussian jurisdictions (↑).9Sławomir Brzozecki, “Kasaty klasztorów w Wilnie w XIX w.”, in: Kasaty klasztorów na obszarze dawnej Rzeczypospolitej obojga narodów i na Śląsku na tle procesów sekularyzacyjnich w Europie, t. 1: Geneza. Kasaty na ziemiach zaborów austriackiego i rosyjskiego (series: Opera ad Historiam Monasticam Spectantia), red. Marek Derwich, Wrocław: Pracownia Badań nad Dziejami Zakonów i Kongregacji Kościelnych-Wrocławskie Towarzystwo Miłośników Historii, 2014, s. 303–304. Though subordinated to government and episcopal levels of authority (as a consequence of forbidding them to elect the protoarchimandrite of the Basilian Order, introduced in 1803), the Greek-Uniate monks preserved autonomy and maintained their usual way of existence. The obligation of superiors to report to the government administration on the communities subordinate to them (holdings, premises, and activities of their members) remained formal and was not done regularly, and episcopal visitations had an internal-ecclesiastical character. Only two times, in 1803 and 1822, did the authorities order detailed descriptions of all Uniate monasteries with the goal of optimizing their network.10НМЛ, Ркл–702, арк. 33.

Signs of a harsher approach appeared in the first years of rule of Emperor Nicholas I. They concerned changes in the boundaries and functions of dioceses. (In particular, in 1828, out of four Commonwealth eparchies, two were created, Lithuanian and Belarusian). In 1829, demands were introduced to annually give the Holy Synod thorough responses to a list of questions (“formulary lists” or “information”), in particular about the social background of each monk, his income, education, social activity, trustworthiness, etc.11Ibid., арк. 54–55. The Greek-Uniate Church was not rescued even by the condemnation of insurrection on the part of Lithuanian Bishop Josafat Bułhak in the form of a pastoral letter for the clergy published in December 1830. In 1832, when some 200 monks (who had been baptized in infancy as Roman Catholics) were forced to leave the Basilian Order, the second period in relations between the Russian authorities and the Uniates began. Uniate monasticism had fallen under the attentive watch of the bishops, the Holy Synod, the Ministry of Internal Affairs, and the police. Two-thirds of monasteries were closed or given to the control of the Greek-Russian Church, including the important center of seminary education in Pochaiv, whose occupants were accused of supporting the Polish uprising and placed under investigation. In 1833, the instruments of military governorship in Vilnius opened a mental institution “to prohibit license, debauchery, and free thought among clergy”.12LVIA, f. 378, b. 32. But even these means did not help deter protests on the part of the clergy against the introduction in 1837 of Orthodox liturgical books into the Uniate liturgy.13Bolesław Kumor, op. cit., s. 114.

An important step towards ending the Union was the appointment in 1833 of secular priest Joseph Semashko as Lithuanian bishop [1]. Already in 1827 he had given the emperor a proposal for the “re-union” of Uniates and Orthodox. Throughout the following years, the episcopal consistory, relying on data from the police, regularly accused the monks of moral decline, “a dislike of religious services according to the rite of the Greek-Eastern Church and failure to maintain them, failure to mention the tsar’s family during the litany”, etc.14Иосиф В. Щербицкий, Виленский Свято-Троицкий монастырь, Вильна: Типография Губернского Правления, 1885, c. 120–121. The constant changing of superiors and deans and the closing of monasteries and parishes had their results: the signatures of 1305 priests were gathered in support of the idea of re-union. On 12 February 1839 during the Polotsk council, a decision was passed for the Uniates to become Orthodox, which was approved by the Holy Synod on 23 March [2]. Some 500 priests and monks expressed their disagreement with this decision; they refused to transfer to the Greek-Russian Church and were deprived of clerical status and expelled.15Marian Radwan, op. cit., s. 220–222. The further closing of monasteries, for example, in 1841 and 1865, respectively, of the women’s (↑) and men’s monasteries of the Holy Trinity in Vilnius, witness the existence of concealed disagreement. The majority of clergy, at least formally, agreed with conversion for the following reasons: fear of repression; the example of the bishops; and not wanting to lose their usual, fairly secure level of living.

Similar motives directed the clergy of the Cholm Eparchy (which had 270 parishes and more than 220 thousand faithful), whose representatives (under pressure from the Greek-Russian Church and its wave of seizures of Uniate church buildings with military support) announced on 20 March 1875 at the Cholm council in the name of 240 priests an intention to transfer to Orthodoxy, which Alexander II approved on 4 April. Formally, the history of the Union in the Russian Empire had ended, though to the start of the 20th century a number of faithful in the Cholm and Podlasie areas continued secretly to maintain the liturgies and rites of the Greek-Uniate Church, which secret Jesuit missions encouraged.16Robert Danieluk, Tajna misja jezuitów na Podlasiu (1878–1904). Wybór dokumentów z archiwów zakonnych Krakowa, Rzymu i Warszawy (series: Studia i materiały do dziejów jezuitów polskich, t. 16), Warszawa: WAM, 2009.

Fate

Among the Basilian monasteries of the Lithuanian Province, Holy Trinity was the most profitable. This was influenced by the location of the monastery in the very center of Vilnius and also by the significant growth of prices for agricultural products in the years of the continental blockade and its status as an agricultural producer. An increase in the price of rents from real estate renters in the city, where between 1807 and 1812 a short-term flowering of demand for expensive goods (for example, fashionable clothes and carriages) was observed, brought a good income. Popular among visitors were restaurants and jewelry stores, and palaces and townhouses were actively being built.21Daniel Beauvois, Wilno – polska stolica kulturalna zaboru rosyjskiego 1803–1832, Wrocław: Uniwersytet Wrocławski, 2012, s. 27. The monastery’s capital funds consisted of 321 thalers, 796 gold coins, and 37162 Polish złoty. The monastery’s annual profit as of 1804 was 4588 silver rubles; in 1819 it was 6333 rubles and 45 silver kopecks.22Marian Radwan, op. cit., s. 170–171. The structure of the revenue side of the monastery’s budget was as follows:

- the sale of agricultural products of the monastery’s Swirany grange brought 2898 rubles, 45 kopecks;

- the annual rent from rental buildings and land plots in Vilnius brought 2685 rubles;

- profit from taverns in the mentioned grange brought 590 rubles;

- interest from loans brought 160 rubles.23НГАБ, ф. 136, воп. 1, адз. зах. 41257, л. 140v–141.

The monastery was also a significant site of agricultural and financial activities, the character of which correlated with declared sources of income [3].

Holy Trinity Monastery in Vilnius possessed eight two- and three-story buildings, and also three plots of land. The majority of buildings were gifts from secular benefactors in the monastery’s benefice, made between 1588 and 1702, under the condition that the profits be used to support the monks and their educational activities. As for the condition of these buildings, three of them, namely, Sawaniewska, Buchnerowska, and Piatnicka, in the first decades of the 19th century needed significant repair, the general cost of which was estimated at approximately 5000 silver rubles. As for the land plots, the one “at the end of the Sharp Gate, at the crossroad right of the garden” (received in 1727) and another, located in the suburb of Lukiškės (acquired in 1644), rented for a long time by Jewish businessmen, ceased bringing a profit.24Ibid., л. 137, 142v. The revenue side of the monastery’s budget was significantly reduced after the Russian government published an order forbidding that ecclesiastical property be rented by Jews. In 1837, total profits were 3327 rubles, 50 kopecks.25LVIA, f. 1178, ap. 1, b. 91, l. 26.

After the War of 1812, the repair of residential premises was an urgent need. As a result of placing a French hospital in the monastery, cells, the refectory, classrooms, and the library were ruined, and wooden frames and doors, furniture and some of the books were burned.26Virgilijus Pugačiauskas, The French Period in Vilnius, Vilnius: Ministry of National Defence, 2013, p. 25. Even seven years after these events, “this monastery… is still not entirely finished, particular the fourth floor, library, and bell-tower”. In 1819 alone, 400 silver rubles were spent on the repair of the fourth floor of the monastery and the bell-tower.27НГАБ, ф. 136, воп. 1, адз. зах. 41257, л. 145v. In addition to these exceptional expenses, there were also the daily ones:

- taxes for the villagers to consume alcoholic drinks, 15 rubles, 45 kopecks;

- for the office of the leader of the nobility, 16 rubles, 40 kopecks;

- capitation for 812 villagers, 259 rubles, 50 kopecks;

- excise duties for the preparation of alcoholic drinks, 421 rubles, 25 kopecks;

- an obligation given by the government for the monastic community to house eight medical students (lodging, service, heating), 240 rubles;

- for the monks’ clothing, 607 rubles, 50 kopecks;

- ecclesiastical-liturgical needs, wine, oil, wax, 230 rubles, 20 kopecks;

- for the annual upkeep of the monks, 1077 rubles, 20 kopecks;

- payment for the services of a doctor, 165 rubles;

- for craftsmen and materials for repair, 1045 rubles, 90 kopecks;

- for food – fish, linseed oil, beef, vegetables, honey, etc., 2605 rubles, 32 kopecks.

The description of very old items in the cell of the hegumen and utensils and instruments in the kitchen indicate a certain degree of luxury in the consumption of food and drinks. Among items on the list: 2 coffee pots, 4 tin vessels with covers for making tea, 24 beer glasses, 20 larger and 2 smaller glasses for strong drinks, 3 beer pumps, a copper pot, and a spit for frying meat. The annual monetary cost to maintain a regular monk was 22 silver rubles, 50 kopecks, and for a local who taught in the school or carried out some administrative duties 30 rubles; for the hegumen, 45 rubles.28LVIA, f. 1178, ap. 1, b. 91, l. 35–116.

In 1839 all the inhabitants transferred to the Greek-Russian Church.29Marian Radwan, op. cit., s. 220–222. Despite the conversion, the monks were considered undependable, and attempts to wean them from elements of the Latin rite during liturgical practices were ineffective.30LVIA, f. 1178, ap. 1, b. 102, l. 1. Among them was observed “a coldness and negligence towards liturgical services”. And so a special notebook was maintained to keep a record of those who were absent or came late to Liturgy. For each instance of a violation, 10 silver kopecks were taken from the monk’s allowance.31Ibid., l. 5.

On 14 March 1845, an imperial decree lowered Holy Trinity Monastery from the 1st to the 3rd (lowest) class. The decree also ordered the transfer to Vilnius of Zyrowycka Seminary, which was to be located in the building of this monastery. Holy Trinity Monastery was formally closed in 1865. This became possible because the majority of the former Uniate monks left this world [4, 5].

Vadym Adadurov

Išnašos:

| 1. | ↑ | Поділ Київської та піднесення Галицької унійних митрополій: документи та матеріали ватиканських архівів 1802–1808 рр. (series: Київське християнство, т. 19), упор. Вадим Ададуров, Львів: Видавництво Українського католицького університету, с. 88. |

|---|---|---|

| 2. | ↑ | Bolesław Kumor, Historia Kościoła, cz. 7: Czasy najnowsze 1815–1914, Lublin: KUL, 1991, s. 101. |

| 3. | ↑ | Larry Wolff, “The Uniate Church and the partitions of Poland: Religious Survival in an Age of Enlightened Absolutism”, Harvard Ukrainian Studies, 2002–2003, vol. 26, no. 1/4, p. 153–244. |

| 4. | ↑ | Поділ Київської…, с. 78. |

| 5. | ↑ | Фундація Галицької митрополії у світлі дипломатичного листування Австрії та Святого Престолу 1807–1808 років: Збірник документів, вступна стаття та коментарі Вадим Ададуров, Львів: Видавництво Українського католицького університету, 2011, с. XXXVI. |

| 6. | ↑ | Вадим Ададуров, Социокультурная история русского похода Наполеона, т. 1: Религия–язык, Киев: Лаурус, 2017, с. 234–235. |

| 7. | ↑ | Дзяніс Лісейчыкаӯ, Святар у беларускім соцыуме: Прасапаграфія беларускаго ӯніяцкага духовенства 1596–1839, Мінск: Нацыянальны гістарычны архів Беларусі, 2015, с. 27, 80–81. |

| 8. | ↑ | Marian Radwan, “Bazylianie w zaborze rosyjskim w latach 1795–1839”, Nasza Przeszłość, 2000, t. 93, s. 220–222. |

| 9. | ↑ | Sławomir Brzozecki, “Kasaty klasztorów w Wilnie w XIX w.”, in: Kasaty klasztorów na obszarze dawnej Rzeczypospolitej obojga narodów i na Śląsku na tle procesów sekularyzacyjnich w Europie, t. 1: Geneza. Kasaty na ziemiach zaborów austriackiego i rosyjskiego (series: Opera ad Historiam Monasticam Spectantia), red. Marek Derwich, Wrocław: Pracownia Badań nad Dziejami Zakonów i Kongregacji Kościelnych-Wrocławskie Towarzystwo Miłośników Historii, 2014, s. 303–304. |

| 10. | ↑ | НМЛ, Ркл–702, арк. 33. |

| 11. | ↑ | Ibid., арк. 54–55. |

| 12. | ↑ | LVIA, f. 378, b. 32. |

| 13. | ↑ | Bolesław Kumor, op. cit., s. 114. |

| 14. | ↑ | Иосиф В. Щербицкий, Виленский Свято-Троицкий монастырь, Вильна: Типография Губернского Правления, 1885, c. 120–121. |

| 15. | ↑ | Marian Radwan, op. cit., s. 220–222. |

| 16. | ↑ | Robert Danieluk, Tajna misja jezuitów na Podlasiu (1878–1904). Wybór dokumentów z archiwów zakonnych Krakowa, Rzymu i Warszawy (series: Studia i materiały do dziejów jezuitów polskich, t. 16), Warszawa: WAM, 2009. |

| 17. | ↑ | LVIA, f. 515, ap. 15, b. 5, l. 26–26r; НМЛ, Ркл–702, арк. 39–39 зв.; Иосиф Семашко, Записки митрополита Литовского, т. 2, Санкт-Петербург: Императорская Академия наук, 1883, с. 6. |

| 18. | ↑ | LVIA, f. 515, ap. 15, b. 5, l. 29; Иосиф Семашко, op. cit., т. 2, с. 6. |

| 19. | ↑ | LVIA, f. 1178, ap. 1, b. 91, l. 35–116. |

| 20. | ↑ | Иосиф Семашко, op. cit., т. 1, с. 61. |

| 21. | ↑ | Daniel Beauvois, Wilno – polska stolica kulturalna zaboru rosyjskiego 1803–1832, Wrocław: Uniwersytet Wrocławski, 2012, s. 27. |

| 22. | ↑ | Marian Radwan, op. cit., s. 170–171. |

| 23. | ↑ | НГАБ, ф. 136, воп. 1, адз. зах. 41257, л. 140v–141. |

| 24. | ↑ | Ibid., л. 137, 142v. |

| 25. | ↑ | LVIA, f. 1178, ap. 1, b. 91, l. 26. |

| 26. | ↑ | Virgilijus Pugačiauskas, The French Period in Vilnius, Vilnius: Ministry of National Defence, 2013, p. 25. |

| 27. | ↑ | НГАБ, ф. 136, воп. 1, адз. зах. 41257, л. 145v. |

| 28. | ↑ | LVIA, f. 1178, ap. 1, b. 91, l. 35–116. |

| 29. | ↑ | Marian Radwan, op. cit., s. 220–222. |

| 30. | ↑ | LVIA, f. 1178, ap. 1, b. 102, l. 1. |

| 31. | ↑ | Ibid., l. 5. |

Sources of illustrations:

| 1. | Held in: LNDM, LNDM T 4482 (Available at: Lietuvos integrali muziejų informacinė sistema, www.limis.lt/greita-paieska/perziura/-/exhibit/preview/20000001729965?s_id=lT538JyuBItDk8Yz&s_ind=29&valuable_type=EKSPONATAS, accessed: 2021 12 01). |

| 2. | Published in: Lietuva medaliuose = Lithuania in medals: XVI a.–XX a. pradžia, sud. Vincas Ruzas, Vilnius: Vaga, 1998, p. 157 (il. 355, 356) [Held in LDM]; Награды императорской России 1702–1917 гг., available at: http://medalirus.ru/stati/medal-na-vossoedinenie-uniatov-s-pravoslavnoyu-tserkovyu.php, accessed: 2021 12 01. |

| 3. | Held in: VUB, Rankraščių skyrius, f. 4, b. (A750) 28491. |

| 4. | [Vilnius: Photo studio of Jan Bułhak], [1913–1915]. Held in: LMAVB, Retų spaudinių skyrius, SFg-2403/2/1 (Available at: “Vilniaus stačiatikių vienuolynas ir Šv. Dvasios cerkvė bei Švenčiausiosios Trejybės bažnyčia ir buvęs Bazilijonų vienuolynas”, in: Lietuvos mokslų akademijos Vrublevskių biblioteka. Skaitmeninis archyvas, http://elibrary.mab.lt/handle/1/6248, accessed: 2021 12 01). | 5. | [Postcard], Cabinet Portrait. Published in: “Bazilijonų vienuolyno vartai Vilniuje” [6. Senoji fotografija, nr. 189], in: ARSVIA, available at: https://arsvia.lt/189-bazilijonu-vienuolyno-vartai-vilniuje, accessed: 2021 12 01. |