Before the Union of Brest, there existed on the territory of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania a number of monasteries of Orthodox women, in Polotsk, Pinsk, and Mogilev.1Олег Дух, Превелебні панни: Жіночі чернечі спільноти Львівської та Перемишльської єпархій у ранньомодерний період (series: Київське християнство, т. 5), Львів: Видавництво УКУ, 2017, с. 59. In the 16th century, a women’s monastic community also arose at Holy Trinity Church in Vilnius. The first reliable reference to it dates to 1589: in the privileges of Sigismund III Vasa, by which the monarch approved the rule of the Holy Trinity brotherhood, it is indicated that the brothers are obliged weekly to provide funds “for food” not only for the local monks but also for the nuns.2Акты, издаваемые Виленскою Археографическою комиссиею, т. 9: Акты Виленского Земского суда, Вильна: Тип. А. Г. Сыркина, 1879, с. 142.

The first known superior of the monastery was Sapieżanka Barbara (Wasylysa), the daughter of the voievod of Minsk, Bohdan Sapieha (↑).3Иосиф В. Щербицкий, Виленский Свято-Троицкий монастырь, Вильна: Типография Губернского Правления, 1885, с. 130. In 1609, she is mentioned as the hegumena of the monastery, which at that time was already Uniate. Through the first half of the 17th century, the material foundations necessary for the proper functioning of the community were laid, Numerous grants were confirmed in 1639 by privilege of Władysław IV.4ЦДІАЛ України, ф. 201, оп. 4б, спр. 429, арк. 35–35зв.

The dynamic development of the monastic community was interrupted by the actions of the Russo–Polish War of 1654–1667. In August 1655, before the occupation of Vilnius by Tsar Aleksey Mikhaylovich, the nuns decided to leave the city. Fleeing, they gathered the most valuable items, including “a large chest, chained with iron, with various legal documents, the privileges for the Vilnius monastery itself, and also various rights regarding the Ashmyany grange”. However, the boat which held the sisters was shot at by a Muscovite detachment, and the chest with the documents sank into the Vilia River.5Ibid., арк. 16–16зв. Little is known of the fate of the community during the Muscovite occupation. It should be mentioned that the single nun of Holy Trinity Monastery who did not leave the city was Sister Marta.6XVII a. vidurio Maskvos okupacijos Lietuvoje šaltiniai, t. 2: 1655–1661 m. Rusų okupacinės valdžios Lietuvoje dokumentai, par. Elmantas Meilus, Vilnius: Lietuvos istorijos instituto leidykla, 2011, p. 348. Some of the nuns found refuge in the territory of the Duchy of Prussia.7Sławomir Augusiewicz, “Spis uchodźców z Wielkiego Księstwa Litewskiego w Prusach Książęcych w latach 1655–1656 w zbiorach Geheimes Staatsarchiv Preussischer Kulturbesitz w Berlinie”, Komunikaty Mazursko-Warmińskie, 2011, t. 1 (271), p. 108, 114, 125, 126, 151, 152, 166.

After the liberation of Vilnius (1661), the nuns returned to their monastery. The monastic center continued to enjoy popularity among the burghers of Vilnius who, in particular, sent their children there for upbringing. The daughters of representatives of the ruling elite of Vilnius also chose monastic life at this Uniate monastery. Among the nuns of the time there are mentions of the daughters of Councilor Jakub Sokołowski and Burgomaster Piotr Minkiewicz. Noble ladies also sought tonsure at this monastery.8Акты…, т. 9, с. 261–264, 298–300; Ibid., т. 15: Декреты Главного литовского трибунала, Вильна: Тип. А. Г. Сыркина, 1888, с. 214–217.

The first half of the 18th century was an especially difficult period in the history of Vilnius. During the time of the Great Northern War, the city passed from one power to another. In 1702, after its occupation by Swedish soldiers, the community of the city was forced to pay a significant contribution, and monastic communities also took part. (The sisters of Holy Trinity Monastery were obligated to pay 30 zł.) Another misfortune for Vilnius was fires. The most ruinous for the city happened in 1737 and 1748, when almost the entire city center burned down.9Józef Ignacy Kraszewski, Wilno od początków jego do roku 1750, t. 2, Wilno: Nakładem i drukiem Józefa Zawadzkiego, 1840, s. 172, 177. The buildings of the Basilian nuns were also damaged. With no money for repair, the nuns gradually got rid of their real estate.10LMAVB, Rankraščių skyrius, f. 41, b. 220, l. 236; Акты…, т. 9, с. 329–332, 388–390.

We learn more about the history of the monastery from the end of the 18th to the first third of the 19th centuries. The monastery complex, which was created as a result of the combination of two city buildings, had two floors and three wings. A report from 1804 notes 19 monastic cells, and also kitchens, a refectory, a cellar, storage areas, and lodging for servants. Maintenance buildings existed separately: a brewery, stable, and shed.11ЦДІАЛ України, ф. 201, оп. 4б, спр. 430, арк. 12.

The nuns did not have their own church, so they came to Holy Trinity Church for services. With the cloister in mind, the choir lofts of this church had a special place given to them, protected from outside eyes. For their use in prayer, the nuns also used the Chapel of the Exaltation of the Holy Cross, built by the left nave. In fact, services were held there seldom; generally, the nuns went to confession there, and during Divine Liturgy they received Communion, coming down from the choir loft.12VUB, Rankraščių skyrius, f. 4, b. A750, l. 2; Ibid., b. A755, l. 3v. It was possible to enter the chapel and the choir loft both from Holy Trinity Church and also directly from the women’s monastery, in this way avoiding meetings with secular persons who came to the church for services. With this goal, in 1792 a closed wooden gallery, resting on brick pillars, was made from the monastery through the bell-tower (↑).13Иосиф В. Щербицкий, op. cit., с. 132.

After Vilnius came under Russian jurisdiction, for a quarter century up to 20 nuns regularly lived in the monastery, though during the existence of the Commonwealth more than 20 lived there.14ЦДІАЛ України, ф. 201, оп. 4б, спр. 430, арк. 12зв. However, among the Basilian women’s monasteries operating at the start of the 19th century, the Vilnius community was one of the largest. In 1806 it had 13 sisters. The only larger ones were in Minsk (23) and Vitebsk (19). The other communities had less inhabitants than Vilnius: Polotsk (12), Orsha (11), Dubno (8), Polonne (8), Pinsk (7), Grodno (5), Novogrudok (5), and Vladimir (5).15Marian Radwan, “Bazylianie w zaborze rosyjskim w latach 1795–1839”, Nasza Przeszłość, 2000, t. 93, s. 164, 168, 174.

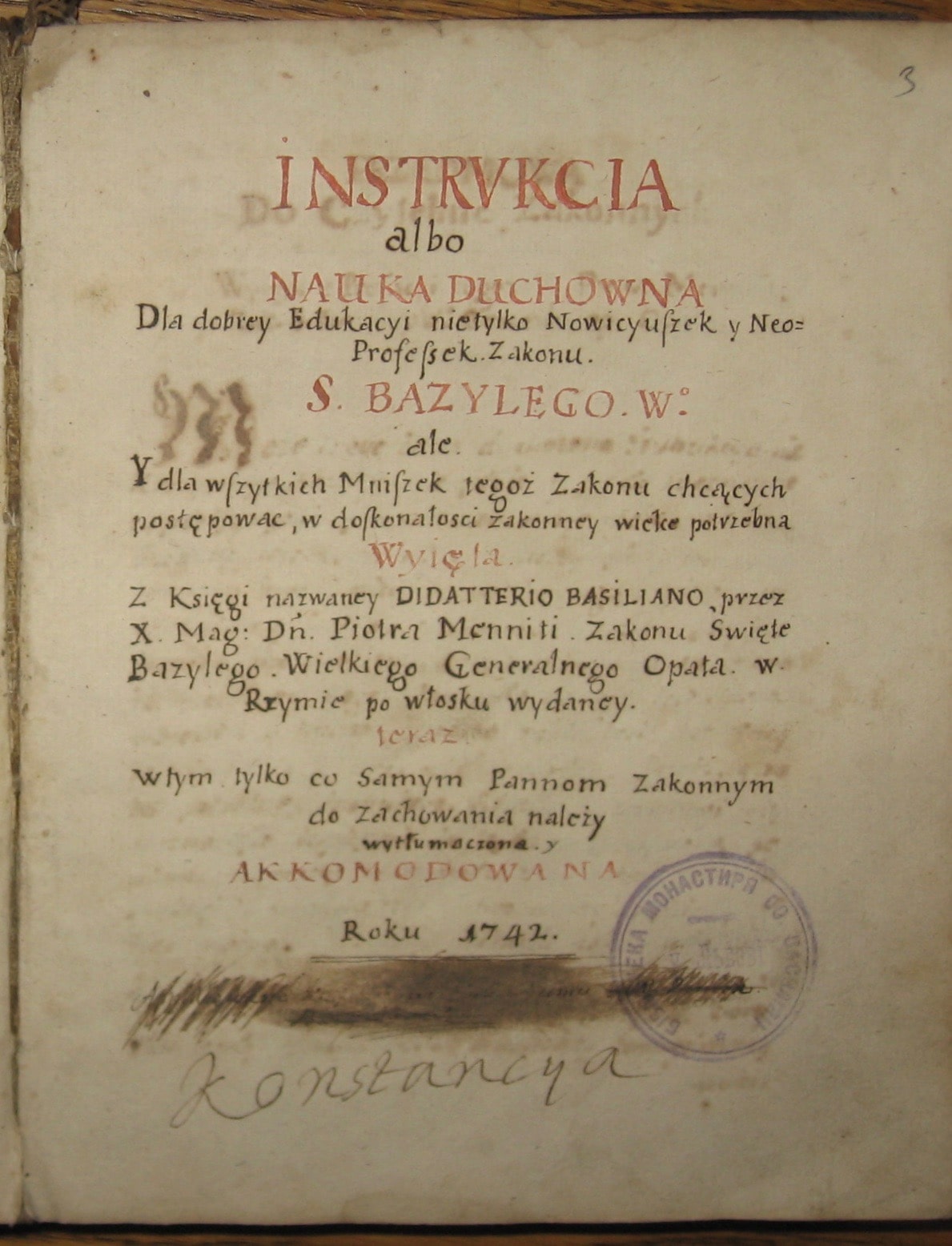

Practically all the nuns at the Vilnius monastery at that time came from the middle-class and petty nobility from Lithuanian–Belarusian lands of the former Commonwealth. For example, Joanna Ważyńska, for many years the hegumena of the monastery, was the daughter of Ashmyany chamberlain Marcin Ważyński.16LMAVB, Retų spaudinių skyrius, f. L-18, b. 536, l. 3; Акты…, т. 9, с. 84–86. Konstancya Jeleńska was the daughter of the territorial judge of the Mazyr district [1]. One of her nieces, also named Jeleńska, was also a Basilian in Vilnius and another – a Visitation sister in the same place.17Małgorzata Borkowska, Leksykon zakonnic polskich epoki przedrozbiorowej, t. 3: Wielkie Księstwo Litewskie i Ziemie Ruskie Korony Polskiej, Warszawa: Wyd-wo DiG, 2008, s. 174.

In addition to their prayer schedule, the nuns also conducted activities which today could be called educational-formational, and “tutelary”. The Basilian nuns accepted girls for education. At the start of the 19th century, the educational program was entirely “early modern” and was limited to learning to read and write, the laws of God, and handwork.18ЦДІАЛ України, ф. 201, оп. 4б, спр. 430, арк. 3. Eventually, the sisters’ school received the status of a private boarding school and provided more thorough knowledge. In 1839, the following subjects were taught: the laws of God, the Russian, Polish, French, and German languages, arithmetic, calligraphy, general history, geography, music, and dance. The majority of teachers at the boarding school were at the same time teachers at the Vilnius Institute for Nobility (formerly the Second Gymnasium). At that time, the sisters had 53 girls at the school, all of noble background. Of these, five were supported by the monastery. The others paid for their own education.19LVIA, f. 567, ap. 2, b. 4385, l. 45v–46. In addition, for an appropriate sum, secular persons resided at the monastery. (In 1816 there were 46.) Some of them, the poor, were supported by the monastery. The sisters also fed beggars who came to the monastery gate.20ЦДІАЛ України, ф. 201, оп. 4б, спр. 430, арк. 3, 70; Ibid., спр. 431в, арк. 225зв.–226.

The main material support of the monastery was the Dauksziszki (Ashmyany of Naruszewicz) grange, located seven miles from Vilnius, in Ashmyany district, which was still a foundation of Lev Sapieha. In January 1803, the monastic estates compromised 163 voloks. The sisters had under them 94 families of serfs and 9 families of city-based subjects.21Ibid, спр. 429б, арк. 4–8; Ibid., спр. 430, арк. 71зв.–72.

After the Union was liquidated in the Russian Empire in 1839, the fate of the Basilian sisters was decided. In 1840, the sisters’ boarding school was liquidated, and a year later, according to the orders of the Holy Synod, enforced by a corresponding imperial decree of 29 April 1841, the women’s monastery ceased to exist.22LVIA, f. 1178, ap. 1, b. 91, l. 1; Ibid., f. 567, ap. 2, b. 4526, l. 7v–8.

Oleh Dukh

Išnašos:

| 1. | ↑ | Олег Дух, Превелебні панни: Жіночі чернечі спільноти Львівської та Перемишльської єпархій у ранньомодерний період (series: Київське християнство, т. 5), Львів: Видавництво УКУ, 2017, с. 59. |

|---|---|---|

| 2. | ↑ | Акты, издаваемые Виленскою Археографическою комиссиею, т. 9: Акты Виленского Земского суда, Вильна: Тип. А. Г. Сыркина, 1879, с. 142. |

| 3. | ↑ | Иосиф В. Щербицкий, Виленский Свято-Троицкий монастырь, Вильна: Типография Губернского Правления, 1885, с. 130. |

| 4. | ↑ | ЦДІАЛ України, ф. 201, оп. 4б, спр. 429, арк. 35–35зв. |

| 5. | ↑ | Ibid., арк. 16–16зв. |

| 6. | ↑ | XVII a. vidurio Maskvos okupacijos Lietuvoje šaltiniai, t. 2: 1655–1661 m. Rusų okupacinės valdžios Lietuvoje dokumentai, par. Elmantas Meilus, Vilnius: Lietuvos istorijos instituto leidykla, 2011, p. 348. |

| 7. | ↑ | Sławomir Augusiewicz, “Spis uchodźców z Wielkiego Księstwa Litewskiego w Prusach Książęcych w latach 1655–1656 w zbiorach Geheimes Staatsarchiv Preussischer Kulturbesitz w Berlinie”, Komunikaty Mazursko-Warmińskie, 2011, t. 1 (271), p. 108, 114, 125, 126, 151, 152, 166. |

| 8. | ↑ | Акты…, т. 9, с. 261–264, 298–300; Ibid., т. 15: Декреты Главного литовского трибунала, Вильна: Тип. А. Г. Сыркина, 1888, с. 214–217. |

| 9. | ↑ | Józef Ignacy Kraszewski, Wilno od początków jego do roku 1750, t. 2, Wilno: Nakładem i drukiem Józefa Zawadzkiego, 1840, s. 172, 177. |

| 10. | ↑ | LMAVB, Rankraščių skyrius, f. 41, b. 220, l. 236; Акты…, т. 9, с. 329–332, 388–390. |

| 11. | ↑ | ЦДІАЛ України, ф. 201, оп. 4б, спр. 430, арк. 12. |

| 12. | ↑ | VUB, Rankraščių skyrius, f. 4, b. A750, l. 2; Ibid., b. A755, l. 3v. |

| 13. | ↑ | Иосиф В. Щербицкий, op. cit., с. 132. |

| 14. | ↑ | ЦДІАЛ України, ф. 201, оп. 4б, спр. 430, арк. 12зв. |

| 15. | ↑ | Marian Radwan, “Bazylianie w zaborze rosyjskim w latach 1795–1839”, Nasza Przeszłość, 2000, t. 93, s. 164, 168, 174. |

| 16. | ↑ | LMAVB, Retų spaudinių skyrius, f. L-18, b. 536, l. 3; Акты…, т. 9, с. 84–86. |

| 17. | ↑ | Małgorzata Borkowska, Leksykon zakonnic polskich epoki przedrozbiorowej, t. 3: Wielkie Księstwo Litewskie i Ziemie Ruskie Korony Polskiej, Warszawa: Wyd-wo DiG, 2008, s. 174. |

| 18. | ↑ | ЦДІАЛ України, ф. 201, оп. 4б, спр. 430, арк. 3. |

| 19. | ↑ | LVIA, f. 567, ap. 2, b. 4385, l. 45v–46. |

| 20. | ↑ | ЦДІАЛ України, ф. 201, оп. 4б, спр. 430, арк. 3, 70; Ibid., спр. 431в, арк. 225зв.–226. |

| 21. | ↑ | Ibid, спр. 429б, арк. 4–8; Ibid., спр. 430, арк. 71зв.–72. |

| 22. | ↑ | LVIA, f. 1178, ap. 1, b. 91, l. 1; Ibid., f. 567, ap. 2, b. 4526, l. 7v–8. |

Sources of illustrations:

| 1. | Held in: ЛННБ ВР, Відділ рукописів, ф. 3, од. зб. 576, арк. 3. |