There are no precise reports of when the men’s and women’s monastic centers arose at Holy Trinity Church. In the second half of the 16th century, the Orthodox men’s monastery is spoken of as one that existed “from ancient times”.1Ihoris Skočiliasas, “Vienuolių bendruomenė Vilniaus viešojoje erdvėje”, in: Vadimas Adadurovas, et al., Kultūrų kryžkelė. Vilniaus Švč. Trejybės šventovė ir vienuolynas, moksl. red. Alfredas Bumblauskas, Salvijus Kulevičius, Ihoris Skočiliasas, Vilnius: Vilniaus universiteto leidykla, 2017, p. 17; same: Ігор Скочиляс, “Prologium: Монаша спільнота василіян у публічному просторі Вільна”, in: Вадим Ададуров, et al., На перехресті культур. Монастир і храм Пресвятої Трійці у Вільнюсі (series: Київське християнство, т. 16), наук. ред. Альфредас Бумблаускас, Сальвіюс Кулявічюс, Ігор Скочиляс, Львів: Український католицький університет, 2019, с. 22–23. At the end of that century, a school and printing press operated at the monastery. In 1587, permission was received to build a brick bell-tower, and in 1595 there is mention of a brick monastic refectory, which the Vilnius (Holy Trinity) brotherhood (↑) also used.2Leonidas Timošenka, “Švč. Trejybės stačiatikių vienuolynas”, in: Vadimas Adadurovas, et al., p. 64; Собрание древних грамот и актов городов Вильны, Ковна, Трок, православных монастырей, церквей и по разным предметам, т. 2, Вильно: Типография А. Марциновского, 1843, с. 23. The start of the 17th century is a new era in the history of this monastic community, when the Uniates received the Holy Trinity Complex.3[Jan Olszewski], Obrona monastyra Wileńskiego cerkwi Przenayświętszey Troycy, y zupełna informacya przez wielebnych OO. Bazylianow wileńskich unitów przy teyże cerkwi zostających, Wilno, 1702, s. B2–C. Orthodox monks who did not support the Union went to Holy Spirit Church, and the monastery that had been at Holy Trinity Church for some time was abandoned. In 1607, a Uniate community of Basilians was founded here. In 1617, it became the center of the Basilian Order. Josyf Veliamyn Rutsky (head of the monastery, 1609–1611, and from 1614 Kyivan metropolitan) (↑) and Josaphat Kuntsevych (hegumen of the Basilians, 1611–1617) (↑) are considered the main founders of the new monastic order.4Pavlo Krečiunas, Vasilis Parasiukas, “Švč. Trejybės unitų vienuolynas ir Bazilijonų ordino steigimas”, in: Vadimas Adadurovas, et al., p. 80–91; same: Павло Кречун, Василь Парасюк, “Святотроїцький унійний монастир і реформа 1617 року”, in: Вадим Ададуров, op. cit., с. 115–132. The foundation of the monastery and its continued functioning was, to a significant extent, insured by benefactors, the amount of which constantly grew: they bequeathed their buildings or other property to it, as did city burgomasters and average merchants.

The first reliable references to an Orthodox community of monks reach back to 1589.5Olehas Duchas, “Vienuolės”, in: Vadimas Adadurovas, et al., p. 189; same: Олег Дух, “Жіноча обитель”, in: Вадим Ададуров, op. cit., с. 281–282. After the Union of Brest (↑), it supported a reform of monasticism. The official date of the founding of the monastery of the Basilian sisters is 1610. In this period, it was headed by superior Barbara Sapieżanka. In general, the Sapieha family was one of the most generous benefactors of the new monastic center, and numerous representatives of this family became nuns of this monastery (↑).6Ibid.

At first, the two monasteries had separate, partially wooden, partially brick buildings, situated around a number of internal courtyards.7Археографический сборник документов, относящихся к истории Северо-Западной Руси, издаваемый при управлении Виленскаго учебнаго округа, т. 10, Вильна: Печатня О. Блюмовича, 1874, с. VI. The residential buildings of the men’s monastery, a school, and a printing house stood near the church, and west and south of it were an agricultural building and gardens. In the 17th century, a large part of the monastery land was given to city residents who settled here in their buildings, but at the end of the 18th century they used this space differently – the monastery garden was planted here. The buildings and small garden of the women’s monastery were situated northwest of the men. In the 18th century, the monastery of the Basilian nuns was joined to the church by a brick entrance gallery (destroyed during reconstruction in 1784).8Ibid., т. 12, 1900, с. 139.

The appearance of the monasteries changed significantly after their renewal following the fire of 1760.9According to the description of the construction process in the monastery journal, the renewal and construction of the complex lasted approximately 25 years and was completed after the death of the architect, Johann Christoph Glaubitz (LVIA, f. 1178, ap. 1, b. 374, l. 9, 37). First the agricultural buildings and main monastery gate, which in time became the symbol of the whole complex, were built.10See more: Rasa Butvilaitė, “Vilniaus bazilijonų vienuolyno vartai”, in: Vilniaus architektūros mokykla XVIII–XX a. (series: Acta Academiae Artium Vilnensis = Vilniaus dailės akademijos darbai, t. 2), Vilnius: Vilniaus dailės akademijos leidykla, 1993, p. 161–193. This gate was the creation of architect Johann Christoph Glaubitz (↑). In 1761, according to a project prepared by the same Glaubitz, construction began on new brick buildings. After 1770, they began to repair the bell tower: it was already badly damaged, standing without a roof for over 20 years.11LVIA, f. 1178, ap. 1, b. 374, l. 38v. In 1777, they built a brick wall between the women’s and men’s monasteries. The western residential corpus had already appeared then; the façade and the roof of the porch were adorned by metal vases. With the agreement of the monks, the new premises were also used for the needs of the laity. Thus, in 1779-1780 a session of the Tribunal of the Grand Duke of Lithuania was held in the main hall of the refectory.12LVIA, f. 1178, ap. 1, b. 374, l. 73–73v, 76.

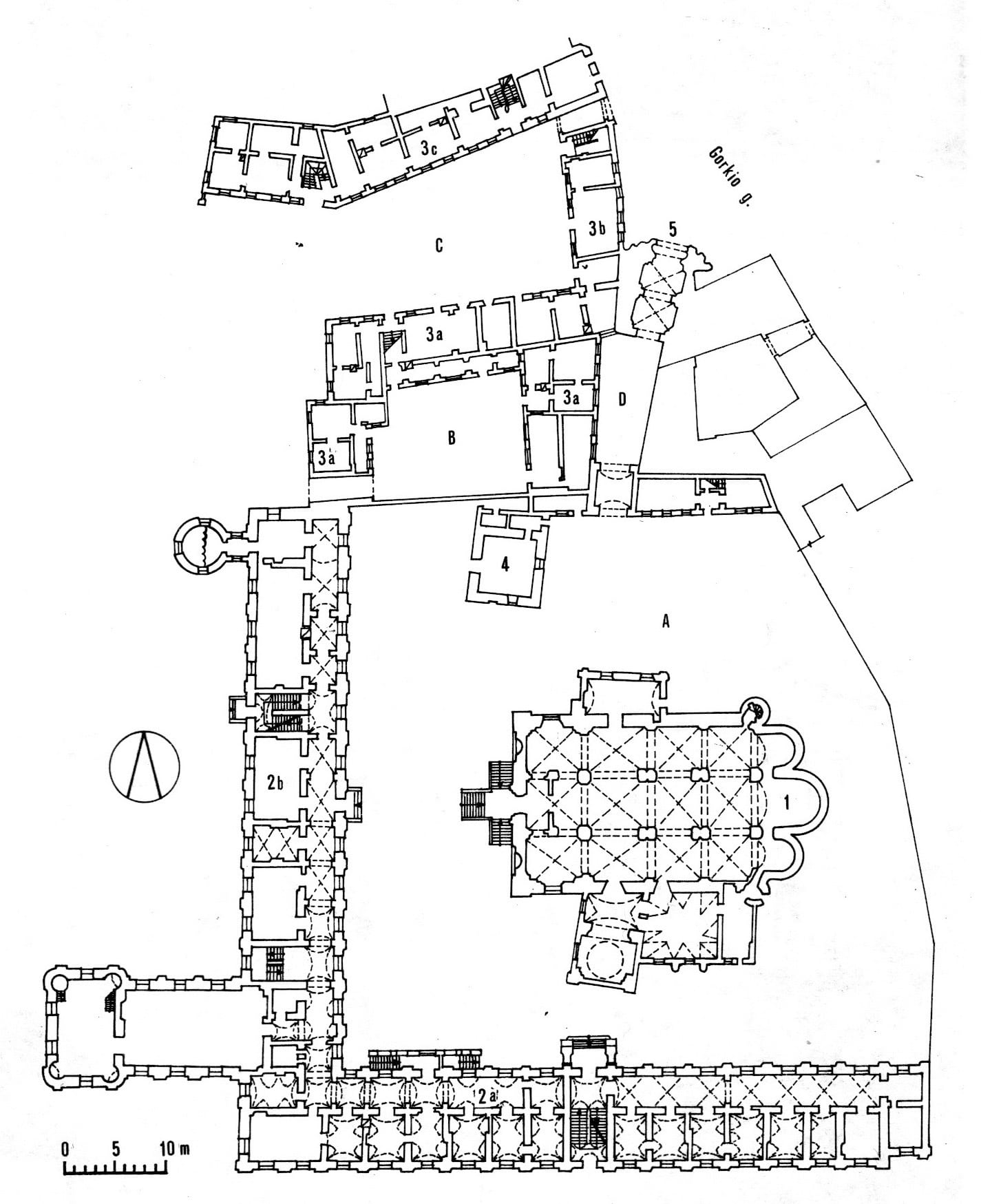

The next stage of the construction of the complex lasted from 1781 to 1792, when the construction of the southern corpus of the monastery was completed.13 Rūta Janonienė, “Architektūrinis ansamblis”, in: Vadimas Adadurovas, et al, p. 215; same: Рута Янонєнє, “Архітектурний ансамбль”, in: Вадим Ададуров, op. cit., с. 317. This work and the reconstruction of the church, which were done in parallel, must have been directed by the very same architect. The brick corridor that joined the men’s monastery with the church arose in this period. In 1792, a new, covered entrance on the arches was built, which went from the lodging of the Basilian sisters through the bell tower to the organ choir and the Chapel of St. Luke [1].14The parts of the church’s organ choir designated for nuns and for musicians were separated by a wooden partition.

We can take a look at the men’s monastery at the start of the 19th century [2]. The entrance to its residential buildings was from the side of the church courtyard, in the northern end of the western corpus. The premises were arranged in a corridor system; the windows of the cells looked into the monastery garden. In total, there were 24 single cells here, seven cells with cellars, 10 rooms for laypeople, and the cells of the superior and the suffragan-bishop were made up of a number of premises. Two halls are mentioned which are called “museums”; they were designated for monks who were students.15VUB, Rankraščių skyrius, f. 4-(A750) 28491, l. 26–29. On the first floor of the western corpus were the refectory, kitchen, storage rooms, and cells. On the first floor of the risalit (extension, facing the west) of this building were printing halls (↑), the vaults of which leaned on three pillars, over which were the same refectory premises, and still higher a beautifully furnished library (↑). Under the risalit were deep vaulted cellars with a well. The first floor of the southern corpus contained various auxiliary premises, vegetable storage rooms, etc.; the second contained the superior’s rooms (a hall decorated with wall paintings, two vaulted cells, also painted, and a wardrobe) ; and the third was the apartment of the suffragan-bishop (three vaulted rooms and a hall). The walls of the most important premises (refectory, library) were decorated with murals and paintings.

In 1812, the French army set up a military hospital in the monastery. It left the complex ruined and devastated. In one of its parts, the rooms of a prison were located later; this was renowned as the place of imprisonment of Adam Mickiewicz and other members of the Philomath Society of Vilnius University (1823–1824). Participants of the November uprising of 1830–1831 were also held here, as was Szymon Konarski, one of the leaders of the movement for the renewal of the Republic of Two Nations, throughout 1838–1839.

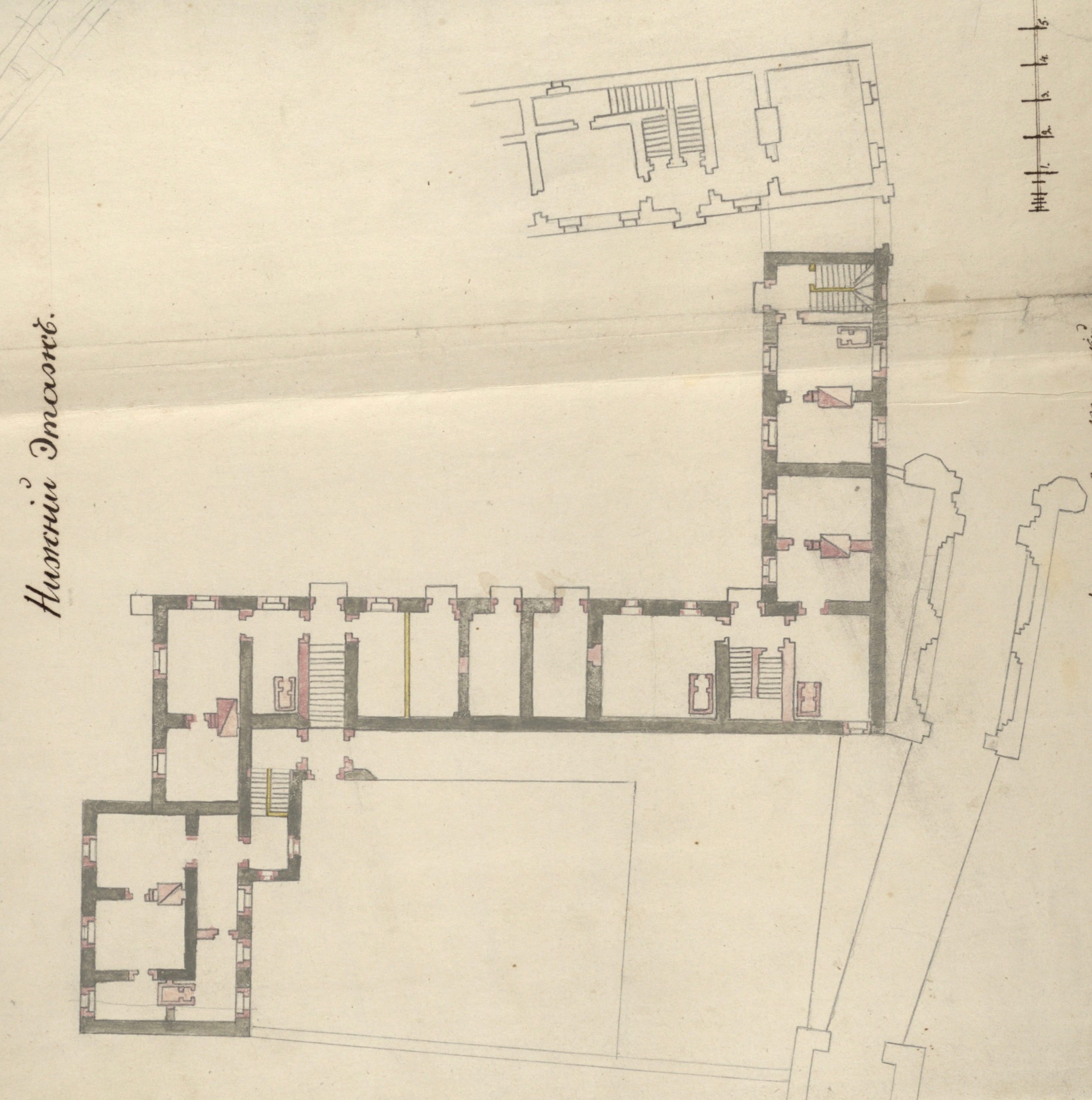

In 1839, the monastic center of the Basilian Fathers was liquidated by the authorities of the Russian Empire. Then the Orthodox Church took over the church building, and Orthodox monks moved into the monastery complex. In 1841, the women’s monastery was closed.16Археографический сборник документов…, с. VI. Already a year before that, the covered gallery that joined the monastery of the Basilian sisters with the church had been demolished [3].

From 1845, an Orthodox seminary operated on these premises. In 1864, Governor General Mikhail Muravyov allotted 60 000 rubles for its capital repair.17Литовскiя епархiальныя ведомости, 1864, ч. 8, с. 259. The buildings reconstructed according to the project of architect Nikolai Chagin were consecrated in 1865, though work continued later.18Ibid., 1865, ч. 17, с. 645–647. In 1867, during the enlargement of some premises, part of the partitions and vaults were destroyed, and a three-story round corpus in the form of a tower was built onto the western façade [4].19A. Jankevičienė, V. Levandauskas, “Švč. Trejybės cerkvės ir bazilijonų vienuolyno pastatų ansamblis M. Gorkio g. 71, 73”, in: Vilniaus architektūra, sud. A. Jankevičienė, Vilnius: Mokslas, 1985, p. 168. New, decorative neobaroque murals adorned the walls of some rooms [5].20Dalia Klajumienė, “Sienų apmušalų imitacija interjeruose nuo gotikos iki moderno”, in: Tekstai apie dizainą: lietuviški ir tarptautiniai kontekstai (series: Acta Academiae Artium Vilnensis = Vilniaus dailės akademijos darbai, t. 61), sud. Karolina Jakaitė, Vilnius: Vilniaus dailės akademijos leidykla, 2011, p. 31.

From 1914 to 1944, a Belarusian gymnasium functioned in some of the buildings of the former men’s monastery, and in 1921 the Ivan Luckievič Belarusian Museum opened here (↑). In the years of Soviet occupation, apartments and premises of educational institutions were housed in these buildings. With the renewal of Lithuanian independence at the end of the 20th century, the church and the complex of the men’s monastery were given to the Vilnius Archdiocese of the Roman Catholic Church in Lithuania. And from 1992, the Basilian Monastery of St. Josaphat renewed its activities in a part of this complex (↑).

Rūta Janonienė

Išnašos:

| 1. | ↑ | Ihoris Skočiliasas, “Vienuolių bendruomenė Vilniaus viešojoje erdvėje”, in: Vadimas Adadurovas, et al., Kultūrų kryžkelė. Vilniaus Švč. Trejybės šventovė ir vienuolynas, moksl. red. Alfredas Bumblauskas, Salvijus Kulevičius, Ihoris Skočiliasas, Vilnius: Vilniaus universiteto leidykla, 2017, p. 17; same: Ігор Скочиляс, “Prologium: Монаша спільнота василіян у публічному просторі Вільна”, in: Вадим Ададуров, et al., На перехресті культур. Монастир і храм Пресвятої Трійці у Вільнюсі (series: Київське християнство, т. 16), наук. ред. Альфредас Бумблаускас, Сальвіюс Кулявічюс, Ігор Скочиляс, Львів: Український католицький університет, 2019, с. 22–23. |

|---|---|---|

| 2. | ↑ | Leonidas Timošenka, “Švč. Trejybės stačiatikių vienuolynas”, in: Vadimas Adadurovas, et al., p. 64; Собрание древних грамот и актов городов Вильны, Ковна, Трок, православных монастырей, церквей и по разным предметам, т. 2, Вильно: Типография А. Марциновского, 1843, с. 23. |

| 3. | ↑ | [Jan Olszewski], Obrona monastyra Wileńskiego cerkwi Przenayświętszey Troycy, y zupełna informacya przez wielebnych OO. Bazylianow wileńskich unitów przy teyże cerkwi zostających, Wilno, 1702, s. B2–C. |

| 4. | ↑ | Pavlo Krečiunas, Vasilis Parasiukas, “Švč. Trejybės unitų vienuolynas ir Bazilijonų ordino steigimas”, in: Vadimas Adadurovas, et al., p. 80–91; same: Павло Кречун, Василь Парасюк, “Святотроїцький унійний монастир і реформа 1617 року”, in: Вадим Ададуров, op. cit., с. 115–132. |

| 5. | ↑ | Olehas Duchas, “Vienuolės”, in: Vadimas Adadurovas, et al., p. 189; same: Олег Дух, “Жіноча обитель”, in: Вадим Ададуров, op. cit., с. 281–282. |

| 6. | ↑ | Ibid. |

| 7. | ↑ | Археографический сборник документов, относящихся к истории Северо-Западной Руси, издаваемый при управлении Виленскаго учебнаго округа, т. 10, Вильна: Печатня О. Блюмовича, 1874, с. VI. |

| 8. | ↑ | Ibid., т. 12, 1900, с. 139. |

| 9. | ↑ | According to the description of the construction process in the monastery journal, the renewal and construction of the complex lasted approximately 25 years and was completed after the death of the architect, Johann Christoph Glaubitz (LVIA, f. 1178, ap. 1, b. 374, l. 9, 37). |

| 10. | ↑ | See more: Rasa Butvilaitė, “Vilniaus bazilijonų vienuolyno vartai”, in: Vilniaus architektūros mokykla XVIII–XX a. (series: Acta Academiae Artium Vilnensis = Vilniaus dailės akademijos darbai, t. 2), Vilnius: Vilniaus dailės akademijos leidykla, 1993, p. 161–193. |

| 11. | ↑ | LVIA, f. 1178, ap. 1, b. 374, l. 38v. |

| 12. | ↑ | LVIA, f. 1178, ap. 1, b. 374, l. 73–73v, 76. |

| 13. | ↑ | Rūta Janonienė, “Architektūrinis ansamblis”, in: Vadimas Adadurovas, et al, p. 215; same: Рута Янонєнє, “Архітектурний ансамбль”, in: Вадим Ададуров, op. cit., с. 317. |

| 14. | ↑ | The parts of the church’s organ choir designated for nuns and for musicians were separated by a wooden partition. |

| 15. | ↑ | VUB, Rankraščių skyrius, f. 4-(A750) 28491, l. 26–29. |

| 16. | ↑ | Археографический сборник документов…, с. VI. |

| 17. | ↑ | Литовскiя епархiальныя ведомости, 1864, ч. 8, с. 259. |

| 18. | ↑ | Ibid., 1865, ч. 17, с. 645–647. |

| 19. | ↑ | A. Jankevičienė, V. Levandauskas, “Švč. Trejybės cerkvės ir bazilijonų vienuolyno pastatų ansamblis M. Gorkio g. 71, 73”, in: Vilniaus architektūra, sud. A. Jankevičienė, Vilnius: Mokslas, 1985, p. 168. |

| 20. | ↑ | Dalia Klajumienė, “Sienų apmušalų imitacija interjeruose nuo gotikos iki moderno”, in: Tekstai apie dizainą: lietuviški ir tarptautiniai kontekstai (series: Acta Academiae Artium Vilnensis = Vilniaus dailės akademijos darbai, t. 61), sud. Karolina Jakaitė, Vilnius: Vilniaus dailės akademijos leidykla, 2011, p. 31. |

Sources of illustrations:

| 1. | Vilda Jakštaitė, Vilniaus bazilijonų vienuolyno Švč. Trejybės cerkvės ir varpinės istorinė–architektūrinė raida: [summary of master’s work], Vilnius: Vilniaus dailės akademija, 2017, p. 25 (19 pav.). Published in: Lietuvos akademinė elektroninė biblioteka [eLABa ID: 22904495], available at: www.lvb.lt/primo-explore/fulldisplay?docid=ELABAETD22904495&context=L&vid=ELABA&lang=lt_LT&search_scope=eLABa&adaptor=Local%20Search%20Engine&tab=default_tab&query=any,contains,Vilniaus%20bazilijonų%20vienuolyno%20Švč.%20Trejybės%20cerkvės%20ir%20varpinės%20istorinė%20–%20architektūrinė%20raida&offset=0, accessed: 2021 12 01. |

| 2. | Published in: Vytautas Levandauskas, „Šventosios Trejybės cerkvės ir bazilijonų vienuolyno ansamblis“, in: Lietuvos TSR istorijos ir kultūros paminklų sąvadas, t. 1: Vilnius, Vilnius: Vyriausioji enciklopedijų leidykla, 1988, p. 236 (il. 156). |

| 3. | Held in: LVIA, f. 604, ap. 1, b. 4970, l. 67. Published in: „Vilniaus bazilijonų vienuolyno statinių ansamblis“ [unique code: 681], in: Kultūros vertybių registras, available at: https://kvr.kpd.lt/#/static-heritage-detail/06cabf58-1daa-4641-af11-c7de1aa4f2c5, photo no. 12, accessed: 2021 12 01. |

| 4. | [Vilnius: Photo studio of J. Bułhak], [1913–1915]. Held in: LMAVB, Retų spaudinių skyrius, SFg-2403/2 (available at: „Vilniaus stačiatikių vienuolynas ir Šv. Dvasios cerkvė bei Švenčiausiosios Trejybės bažnyčia ir buvęs Bazilijonų vienuolynas“, in: Lietuvos mokslų akademijos Vrublevskių biblioteka. Skaitmeninis archyvas, http://elibrary.mab.lt/handle/1/6248, accessed: 2021 12 01). |

| 5. | Private collection of Neringa Šarkauskaitė-Šimkuvienė. Published in: Atgimusios spalvos. Architektės-restauratorės Neringos Šarkauskaitės-Šimkuvienės darbų katalogas, Vilnius, 2020, p. 19. |