Uniate Church

In the 19th century, the structure of the church now known as Greek-Catholic – the historical Kyivan Metropolitanate – was divided by the boundaries of three governments. At the start of the century there existed the Polotsk Archeparchy, the eparchies of Brest and Lutsk in the Russian Empire, the Supraśl Eparchy in the Kingdom of Prussia, the Lviv and Przemyśl eparchies, and also the Mukachevo Eparchy in the Austrian monarchy, subject to the Latin rite archbishop of Esztergom, Hungary. After the Treaties of Tilsit of 1807, the Supraśl Eparchy ended up in the Russian Empire and was included in the Brest district.

The conditions of the GCC in the Habsburg Empire were determined by the policy of enlightened absolutism, which foresaw the strengthening of government control over ecclesiastical matters, but because Greek-Catholics had equal legal status with Roman Catholics, the arrangement of educational and financial affairs led to the improvement of conditions for the development of the church and laid the foundations for its active role in the life of society. In 1807, the pope revived the Metropolitanate of Halych, whose metropolitans inherited the rights of those of Kyiv; the first was Antin Anhelovych. In 1816, they divided the Mukachevo Eparchy from the Prešov Eparchy. In 1833, structures of the Metropolitanate of Halych were formed in Bukovyna.1Нестор Мизак, Андрій Яремчук, Нарис історії УГКЦ на Буковині, Львів–Чернівці: Український католицький університет, 2021, с. 27. In total, in 1839 in the Austrian Empire there were almost 2 500 parishes, 2 700 parish priests, and 2 684 159 faithful of the GCC.2Dmytro Blazejowskyj, Historical Šematism of the Archeparchy of L’viv (1832–1944), vol. 1: Administration and parishes, Kyiv: Києво-Могилянська академія, 2004, p. 918; Dmytro Blazejowskyj, Historical Šematism of the Eparchy of Peremyšl including the Apostolic Administration of Lemkivščyna (1828–1939), Lviv: Kamenyar, 1995, p. 946; Schematismus cleri graeci ritus catholicorum dioecesis Munkácsiensis: Pro anno Domini MDCCCXXXIX, Cassoviae, 1838, p. 281; Schematismus cleri graeci ritus catholicorum dioecesis Eperiessiensis, pro anno Domini MDCCCXXXVII, Cassoviae, 1837, p. 169; Фундація Галицької митрополії у світлі дипломатичного листування Австрії та Святого Престолу 1807–1808 років: Збірник документів (series: Київське християнство, т. 19), ред. Вадим Ададуров, Львів: Видавництво Українського католицького університету, 2011.

The status of the GCC in the empire of the Romanovs was different. In 1795, Metropolitan of Kyiv Theodosius Rostocki under pressure from the authorities moved to St. Petersburg. During the rule of Empress Catherine II, the Uniate Church lost approximately 8 000 000 faithful, 9 316 parishes, and 145 monasteries; nevertheless, in 1803 there were still 1 406 207 Greek-Catholic faithful in the empire.3Начеркъ исторіи уніи рускои церкви зъ Римом, ред. Д. Дорожинскій, Львôвъ: Накладомъ комітету ювилейного, изъ типографіи Ставропигійского института, 1896, с. 82; В. Ленцик, “Українсько-Католицька Церква в Росії до її ліквідації (1772–1839/75)”, Берестейська унія (1596–1996): статті й матеріали, Львів: Логос, 1996, с. 98; Marian Radwan, Kościoł greckokatolicki w zaborze rosyjskim około 1803 roku, Lublin: Instytut Europy Środkowo-Wschodniej, 2003, s. 15. The authorities constantly pressured the church, depriving it of property and identity, controlling the formation of the clergy under the appearance of concern for “the purity of the Eastern rite”, hindering contacts with the Holy See. On 12 February 1839, bishops Józef Siemaszko [1], Antoni Zubko, and Wasyl Łużyński organized a synod in Polotsk, where they decided to join the Russian Orthodox Church. The document of the synod, because of a fear of uprising, was not published until 20 October 1839, though it had been approved by Emperor Nicholas I on 25 March [2].4Вікторія Білик, Оксана Карліна, Жива спільнота в імперському світі: Луцька греко-унійна єпархія кінця XVIII–першої третини ХІХ століть (series: Київське християнство, т. 13), Львів: Видавництво Українського католицького університету, 2018, с. 86–109; Валентина Лось, Уніатська Церква на Правобережній Україні наприкінці XVIII – першій половині ХІХ ст.: організаційна структура та культурно-релігійний аспект, Київ: Друкарня Національної бібліотеки України імені В. І. Вернадського, 2013, с. 81; Святлана Марозава, Уніяцкая Царква у̌ этнакальтурным развіцці Бєларусі (1596–1839 гады), Гродна: ГрДУ, 2001, с. 226–237. In total, in 1839 approximately 1 600 parishes and more than 1 600 000 Greek-Catholics joined the Russian Church. Of the clergy, 1 305 people converted to Orthodoxy and almost 600 refused and 105 dissenting priests were imprisoned.5Надія Стоколос, Руслан Шеретюк, Драма Церкви, Рівне: ПП Дятлик М.С, 2012, с. 116. In protest, part of the faithful and clergy transferred to the Latin rite. The Russian authorities and ROC fought with the “remainders of the Union” even to the last quarter of the 19th century, but sentiments for it remained in right-bank Ukraine and were even expressed in the literary heritage of refugees from families of Uniate clergy, for example, Anatolij Swydnycki.6Анатолій Свидницький, Оповідання. Нариси та статті, Київ: А. С. К., 2006, с. 402, 459, and other. And it is symbolic that a translator of Holy Scripture into the Ukrainian language was a priest of the GCC, Ivan Khomenko, a native of Vinnytsia (↑).7Микола Жукалюк, Дмитро Степовик, Коротка історія перекладів Біблії українською мовою, Київ: Укр. Біблійне Тов–во, 2003, с. 65–73.

Until 1875, the Chełm Uniate Eparchy operated in the empire of the Romanovs, in the autonomous Kingdom of Poland, the process of liquidation of which began after the uprising of 1863–1864. The last bishop, Mychajło Kuzemśkyj, renounced the cathedral and settled in Galicia, though the Holy See did not acknowledge this act. Instead, the authorities received in Chełm the Halych Russophile Marceli Popiel [3]. Under his leadership, the faithful went over to Orthodoxy with the help of the army. When in 1874 residents of the village of Pratulin did not want to go over to Orthodoxy, soldiers killed 13 persons, wounded 180, and many were sent to Siberia. In 1996, the Pratulin martyrs were beatified. In 1874, relics of St. Josaphat the Martyr were hidden in the church in Biała Podlaska, to save them from destruction. After permission was proclaimed in 1905 to change one’s religious affiliation, but without the right to return to the GCC, approximately 170 000 former Greek-Catholics went to Roman Catholicism (↑).

In the first half of the 19th century, representatives of the clergy started a national revival of the Greek-Catholics of Galicia, first in Przemyśl, and then students of the Lviv seminary, led by Markiyan Shashkevych, Yakub Holovatsky, and Ivan Vahylevych, united as the “Rus trinity”, joined in. Their fates reflected the challenges facing Ukraine’s enlighteners: from the beginning, Fr. Shashkevych was not accepted because of his background and he died young, in poverty; Fr. Vahylevych because of a lack of faith went to the Polish side and into Protestantism; and Fr. Holovatsky went to the Russophiles and Orthodoxy, immigrated to the Russian Empire and died in Vilnius.8Михайло Тершаковець, Маркіян Шашкевич та його ідеї на тлі українського відродження, Львів: Видавництво Українського Католицького Університету, 2021. But even in difficult conditions of disorientation, the GCC, headed by Metropolitan Mykhailo Levytsky and Bishop Hryhoriy Yakhymovych, on 10 May 1848 declared that the Ruthenians of the country were part of the great Ruthenian, that is, Ukrainian, nation.9Зорѧ Галицка 1 (1848) 1–3; Головна Руська Рада. Протоколи засідань і книга кореспонденції, ред. Олег Турій, Львів: Інститут Історії Церкви Українського Католицького Університету, 2002 с. 22–23. It should be noted that in the Mukachevo and Prešov eparchies at that same period, the challenges were Russophilism and Magyarophilism (an orientation to the Hungarian elites and assimilation). The priestly families of the GCC gave birth to the secular intelligentsia which took over leadership in the life of society.

The 19th century was the era when the GCC rediscovered its own tradition. In Transcarpathia, memory was revived regarding the founder of the Mukachevo monastery, Lithuanian Duke Fedir Koriatovych. At that time, the GCC began to commemorate the anniversary of the Baptism of Rus by Grand Duke Volodymyr, Equal to the Apostles. In the 19th century, there were several attempts to unite the Ukrainian Greek-Catholics of the Habsburg Empire into a single patriarchate, but these efforts were opposed by the elites of neighboring nations.10Олександер Баран, Питання українського патріярхату в Шашкевичівській добі, Вінніпеґ: Рада Укр. Орг. за Патріярхат Українськ. Катол. Церкві, 1984. The Dobromyl reform of the Basilian Order (1882–1904), conducted by the Jesuits, became a step towards the renewal of church life in the conditions of modernization.11Нарис історії Василіянського Чину святого Йосафата (series: Analecta OSBM, сер. 2, ч. 1, т. 48), Рим: Видавництво ОО Василіян, 1992, с. 324–344.

The era of Metropolitan Andrey Sheptytsky (1901–1944) [4], when the modern identity of the Greek-Catholics of Galicia was established, was decisive for the GCC.12Ліліана Гентош, Митрополит Шептицький: 1923–1939. Випробування ідеалів, Львів: ВНТЛ-Класика, 2015. The religious, cultural, social, and economic projects of Metropolitan Sheptytsky encouraged the development of church and society. He endured the pressure of the Polish authorities in the 1920s and 1930s, aiming at the assimilation of Ukrainians, and within episcopal conferences he united Ukrainian Greek-Catholics of the eparchies of Galicia, Transcarpathia, and the diaspora. Another major figure, close to Sheptytsky, was Mukachevo’s Bishop Petro Gebey (1924–1931), with whose support the Basilians of Galicia conducted a reform of monasticism in Transcarpathia.13Ibid., с. 393–396. During the rule of Bishop Gebey, views on the Ukrainian character of Transcarpathia crystallized; a shining example of this was Fr. Avgustyn Voloshyn, Prime Minister and President of Carpathian Ukraine (1938–1939).

Yet one more challenge facing the GCC in Sheptytsky’s time was connected with migration. The metropolitan visited immigrants in the USA, Canada, Brazil, and Argentina. Through his efforts, Ukrainians in America received hierarchs, the first of which was Soter Ortynsky.

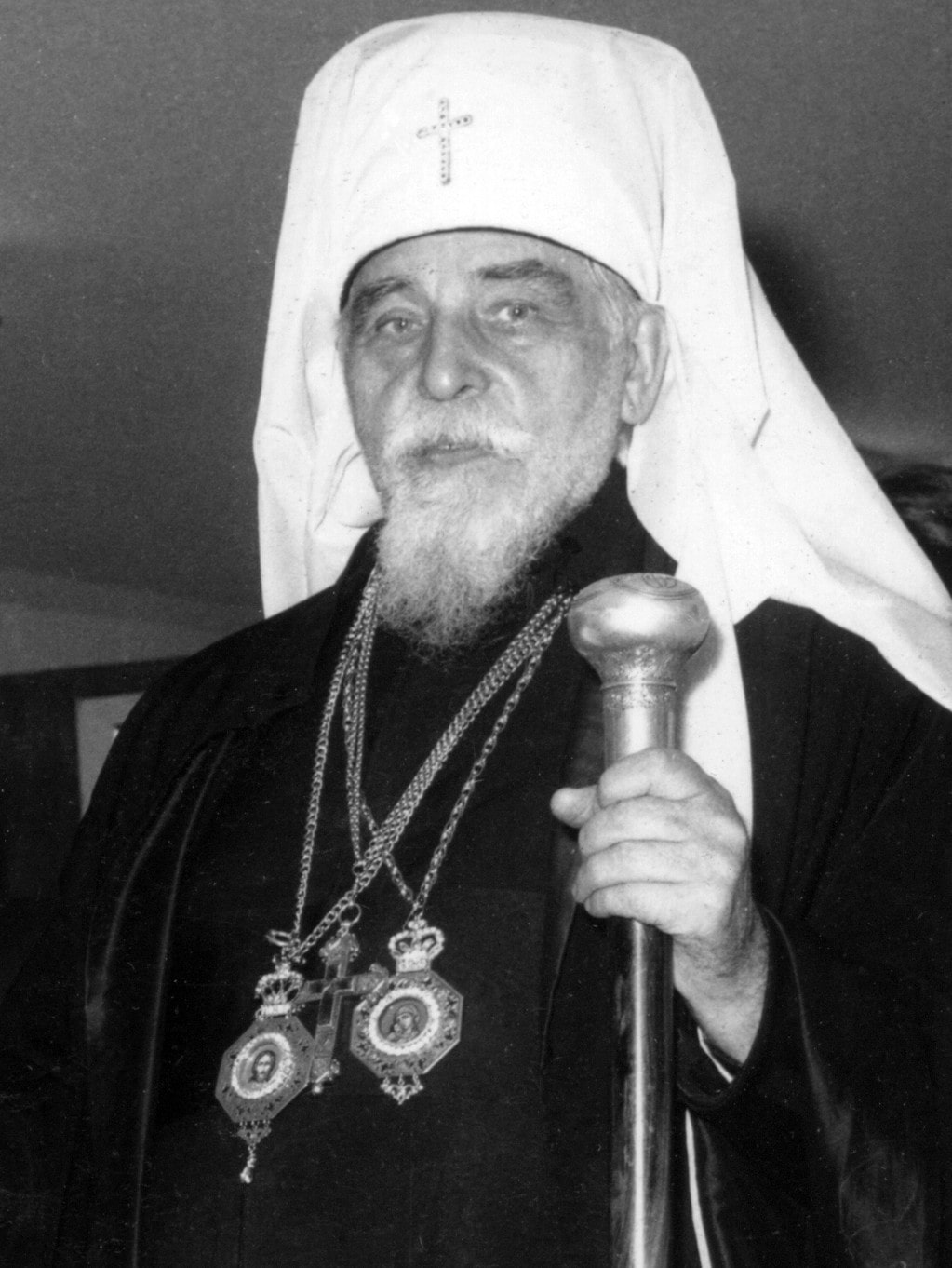

During the Nazi occupation (1941–1944) and the Holocaust, Greek-Catholics rescued many Jews.14Юрій Скіра, Покликані: монахи Студійського уставу та Голокост, Київ: Дух і Літера, 2019. The communist authorities forbid the GCC. From the beginning, the structures of state security of the USSR at the request of Joseph Stalin and Nikita Khrushchev in 1945 arrested all the bishops in the Ukrainian SSR, headed by Metropolitan Josyf Slipyj, and on 8 March 1946 they conducted a pseudo-counsil in Lviv, which ordered a “reunion” with the ROC. They killed Mukachevo Bishop Theodore Romzha as part of a special operation of the Soviet special services.15Павел Судоплатов, Спецоперации. Лубянка и Кремль 1930–1950 годы, Москва: ОЛМА-ПРЕСС, 1998, с. 413–414. In total, approximately 1 200 priests of the GCC in Ukraine under the pressure of the communist regime went over to the ROC. Those who did not agree went into the underground, were persecuted as criminals, were injured and murdered. But the catacomb church survived: hierarchs operated in it, as did pastoral centers and monasteries. Metropolitan Slipyj [5], who lived 18 years in imprisonment, became an example of endurance. The head of the GCC did not accept an offer to become Orthodox metropolitan of Kyiv, even in exchange for his freedom. Metropolitan Slipyj was freed in 1963 thanks to the efforts of Pope John XXIII.16Йосиф Сліпий, Спомини, Львів–Рим: Видавництво Українського католицького університету, 2014, с. 160, 227–228. His Beatitude Slipyj took part in the work of the Second Vatican Council, gathered the communities of the GCC throughout the world, and until his death in 1984 implemented a program for acknowledging the patriarchal dignity of the UGCC.

Along with the movement for perestroika in the USSR, in 1987 some Greek-Catholics in Ukraine announced that they had come out from the underground, but only at the end of 1989 did the authorities agree to acknowledge the UGCC. On 25–26 June 1990, a synod of Ukrainian Greek-Catholic bishops of the whole world was held in Rome, the first since the church was forbidden. On 31 March 1991, the head of the UGCC, Myroslav Ivan Lubachivsky, returned to Ukraine. At the start of the 1990s, the Belarusian GCC also revived, headed by Apostolic Visitator and Protopriest Sergiusz Gajek. Its centers, as in the UGCC, are actively developing in cities where Belarusians have settled in the diaspora. In Lithuania, an important pastoral center of the UGCC is Holy Trinity Monastery in Vilnius, returned in 1991.17Vadimas Adadurovas, “Sunaikinimas”, in: Vadimas Adadurovas, et al., Kultūrų kryžkelė: Vilniaus Švč. Trejybės šventovė ir vienuolynas, moksl. red. Alfredas Bumblauskas, Salvijus Kulevičius, Ihoris Skočiliasas, Vilnius: Vilniaus universiteto leidykla, 2017, p. 150–151; same: Вадим Ададуров, “Закриття”, in: Вадим Ададуров, et al., На перехресті культур: Монастир і храм Пресвятої Трійці у Вільнюсі (series: Київське християнство, т. 16), наук. ред. Альфредас Бумблаускас, Сальвіюс Кулявічюс, Ігор Скочиляс, Львів: Український Католицький Університет, Львів, 2019, с. 228. Ihoris Skočiliasas, “Ukrainietiškoji perspektyva: Kijevo krikščionybės lietuviškųjų ištakų „prisiminimas“, in: Vadimas Adadurovas, op. cit., p. 243–245; same: Ігор Скочиляс, “Українська перспектива”, in: Вадим Ададуров, op. cit., с. 355–378. In Poland, there are three UGCC eparchies, and also monasteries.

On 21 August 2005, the seat of the Head of the UGCC returned to Kyiv. Its Head has the title “Major Archbishop of Kyiv-Halych”, which, according to the “Code of Canons of the Eastern Churches”, indicates a dignity equal to patriarchal. The main church of the UGCC is the Patriarchal Cathedral of the Resurrection of Christ in Kyiv, consecrated on the day of the celebration of the 1025th anniversary of the Baptism of Rus in 2013 [6]. The altar of the cathedral contains relics of the saints and apostles Peter, Paul, and Andrew the First-Called, saints popes Clement and Martin, St. Josaphat Kuntsevych the Martyr (↑), and the martyr bishops Nicholas Charnetsky and Josaphat Kotsylovsky.

Headed by Lubomyr Husar in 2001–2011, and now by Sviatoslav Shevchuk, the church is building up its structures, is an active participant in civil society, and sees its mission in defending human rights. The UGCC has more than 5 500 000 faithfuls throughout the world. In Ukraine there are almost 3 500 communities and more than 2 800 priests of the UGCC; the Mukachevo Greek-Catholic Eparchy has almost 450 communities and 350 priests and is temporarily directly subject to the Holy See.

The conditions of the GCC in the Habsburg Empire were determined by the policy of enlightened absolutism, which foresaw the strengthening of government control over ecclesiastical matters, but because Greek-Catholics had equal legal status with Roman Catholics, the arrangement of educational and financial affairs led to the improvement of conditions for the development of the church and laid the foundations for its active role in the life of society. In 1807, the pope revived the Metropolitanate of Halych, whose metropolitans inherited the rights of those of Kyiv; the first was Antin Anhelovych. In 1816, they divided the Mukachevo Eparchy from the Prešov Eparchy. In 1833, structures of the Metropolitanate of Halych were formed in Bukovyna.1Нестор Мизак, Андрій Яремчук, Нарис історії УГКЦ на Буковині, Львів–Чернівці: Український католицький університет, 2021, с. 27. In total, in 1839 in the Austrian Empire there were almost 2 500 parishes, 2 700 parish priests, and 2 684 159 faithful of the GCC.2Dmytro Blazejowskyj, Historical Šematism of the Archeparchy of L’viv (1832–1944), vol. 1: Administration and parishes, Kyiv: Києво-Могилянська академія, 2004, p. 918; Dmytro Blazejowskyj, Historical Šematism of the Eparchy of Peremyšl including the Apostolic Administration of Lemkivščyna (1828–1939), Lviv: Kamenyar, 1995, p. 946; Schematismus cleri graeci ritus catholicorum dioecesis Munkácsiensis: Pro anno Domini MDCCCXXXIX, Cassoviae, 1838, p. 281; Schematismus cleri graeci ritus catholicorum dioecesis Eperiessiensis, pro anno Domini MDCCCXXXVII, Cassoviae, 1837, p. 169; Фундація Галицької митрополії у світлі дипломатичного листування Австрії та Святого Престолу 1807–1808 років: Збірник документів (series: Київське християнство, т. 19), ред. Вадим Ададуров, Львів: Видавництво Українського католицького університету, 2011.

The status of the GCC in the empire of the Romanovs was different. In 1795, Metropolitan of Kyiv Theodosius Rostocki under pressure from the authorities moved to St. Petersburg. During the rule of Empress Catherine II, the Uniate Church lost approximately 8 000 000 faithful, 9 316 parishes, and 145 monasteries; nevertheless, in 1803 there were still 1 406 207 Greek-Catholic faithful in the empire.3Начеркъ исторіи уніи рускои церкви зъ Римом, ред. Д. Дорожинскій, Львôвъ: Накладомъ комітету ювилейного, изъ типографіи Ставропигійского института, 1896, с. 82; В. Ленцик, “Українсько-Католицька Церква в Росії до її ліквідації (1772–1839/75)”, Берестейська унія (1596–1996): статті й матеріали, Львів: Логос, 1996, с. 98; Marian Radwan, Kościoł greckokatolicki w zaborze rosyjskim około 1803 roku, Lublin: Instytut Europy Środkowo-Wschodniej, 2003, s. 15. The authorities constantly pressured the church, depriving it of property and identity, controlling the formation of the clergy under the appearance of concern for “the purity of the Eastern rite”, hindering contacts with the Holy See. On 12 February 1839, bishops Józef Siemaszko [1], Antoni Zubko, and Wasyl Łużyński organized a synod in Polotsk, where they decided to join the Russian Orthodox Church. The document of the synod, because of a fear of uprising, was not published until 20 October 1839, though it had been approved by Emperor Nicholas I on 25 March [2].4Вікторія Білик, Оксана Карліна, Жива спільнота в імперському світі: Луцька греко-унійна єпархія кінця XVIII–першої третини ХІХ століть (series: Київське християнство, т. 13), Львів: Видавництво Українського католицького університету, 2018, с. 86–109; Валентина Лось, Уніатська Церква на Правобережній Україні наприкінці XVIII – першій половині ХІХ ст.: організаційна структура та культурно-релігійний аспект, Київ: Друкарня Національної бібліотеки України імені В. І. Вернадського, 2013, с. 81; Святлана Марозава, Уніяцкая Царква у̌ этнакальтурным развіцці Бєларусі (1596–1839 гады), Гродна: ГрДУ, 2001, с. 226–237. In total, in 1839 approximately 1 600 parishes and more than 1 600 000 Greek-Catholics joined the Russian Church. Of the clergy, 1 305 people converted to Orthodoxy and almost 600 refused and 105 dissenting priests were imprisoned.5Надія Стоколос, Руслан Шеретюк, Драма Церкви, Рівне: ПП Дятлик М.С, 2012, с. 116. In protest, part of the faithful and clergy transferred to the Latin rite. The Russian authorities and ROC fought with the “remainders of the Union” even to the last quarter of the 19th century, but sentiments for it remained in right-bank Ukraine and were even expressed in the literary heritage of refugees from families of Uniate clergy, for example, Anatolij Swydnycki.6Анатолій Свидницький, Оповідання. Нариси та статті, Київ: А. С. К., 2006, с. 402, 459, and other. And it is symbolic that a translator of Holy Scripture into the Ukrainian language was a priest of the GCC, Ivan Khomenko, a native of Vinnytsia (↑).7Микола Жукалюк, Дмитро Степовик, Коротка історія перекладів Біблії українською мовою, Київ: Укр. Біблійне Тов–во, 2003, с. 65–73.

Until 1875, the Chełm Uniate Eparchy operated in the empire of the Romanovs, in the autonomous Kingdom of Poland, the process of liquidation of which began after the uprising of 1863–1864. The last bishop, Mychajło Kuzemśkyj, renounced the cathedral and settled in Galicia, though the Holy See did not acknowledge this act. Instead, the authorities received in Chełm the Halych Russophile Marceli Popiel [3]. Under his leadership, the faithful went over to Orthodoxy with the help of the army. When in 1874 residents of the village of Pratulin did not want to go over to Orthodoxy, soldiers killed 13 persons, wounded 180, and many were sent to Siberia. In 1996, the Pratulin martyrs were beatified. In 1874, relics of St. Josaphat the Martyr were hidden in the church in Biała Podlaska, to save them from destruction. After permission was proclaimed in 1905 to change one’s religious affiliation, but without the right to return to the GCC, approximately 170 000 former Greek-Catholics went to Roman Catholicism (↑).

In the first half of the 19th century, representatives of the clergy started a national revival of the Greek-Catholics of Galicia, first in Przemyśl, and then students of the Lviv seminary, led by Markiyan Shashkevych, Yakub Holovatsky, and Ivan Vahylevych, united as the “Rus trinity”, joined in. Their fates reflected the challenges facing Ukraine’s enlighteners: from the beginning, Fr. Shashkevych was not accepted because of his background and he died young, in poverty; Fr. Vahylevych because of a lack of faith went to the Polish side and into Protestantism; and Fr. Holovatsky went to the Russophiles and Orthodoxy, immigrated to the Russian Empire and died in Vilnius.8Михайло Тершаковець, Маркіян Шашкевич та його ідеї на тлі українського відродження, Львів: Видавництво Українського Католицького Університету, 2021. But even in difficult conditions of disorientation, the GCC, headed by Metropolitan Mykhailo Levytsky and Bishop Hryhoriy Yakhymovych, on 10 May 1848 declared that the Ruthenians of the country were part of the great Ruthenian, that is, Ukrainian, nation.9Зорѧ Галицка 1 (1848) 1–3; Головна Руська Рада. Протоколи засідань і книга кореспонденції, ред. Олег Турій, Львів: Інститут Історії Церкви Українського Католицького Університету, 2002 с. 22–23. It should be noted that in the Mukachevo and Prešov eparchies at that same period, the challenges were Russophilism and Magyarophilism (an orientation to the Hungarian elites and assimilation). The priestly families of the GCC gave birth to the secular intelligentsia which took over leadership in the life of society.

The 19th century was the era when the GCC rediscovered its own tradition. In Transcarpathia, memory was revived regarding the founder of the Mukachevo monastery, Lithuanian Duke Fedir Koriatovych. At that time, the GCC began to commemorate the anniversary of the Baptism of Rus by Grand Duke Volodymyr, Equal to the Apostles. In the 19th century, there were several attempts to unite the Ukrainian Greek-Catholics of the Habsburg Empire into a single patriarchate, but these efforts were opposed by the elites of neighboring nations.10Олександер Баран, Питання українського патріярхату в Шашкевичівській добі, Вінніпеґ: Рада Укр. Орг. за Патріярхат Українськ. Катол. Церкві, 1984. The Dobromyl reform of the Basilian Order (1882–1904), conducted by the Jesuits, became a step towards the renewal of church life in the conditions of modernization.11Нарис історії Василіянського Чину святого Йосафата (series: Analecta OSBM, сер. 2, ч. 1, т. 48), Рим: Видавництво ОО Василіян, 1992, с. 324–344.

The era of Metropolitan Andrey Sheptytsky (1901–1944) [4], when the modern identity of the Greek-Catholics of Galicia was established, was decisive for the GCC.12Ліліана Гентош, Митрополит Шептицький: 1923–1939. Випробування ідеалів, Львів: ВНТЛ-Класика, 2015. The religious, cultural, social, and economic projects of Metropolitan Sheptytsky encouraged the development of church and society. He endured the pressure of the Polish authorities in the 1920s and 1930s, aiming at the assimilation of Ukrainians, and within episcopal conferences he united Ukrainian Greek-Catholics of the eparchies of Galicia, Transcarpathia, and the diaspora. Another major figure, close to Sheptytsky, was Mukachevo’s Bishop Petro Gebey (1924–1931), with whose support the Basilians of Galicia conducted a reform of monasticism in Transcarpathia.13Ibid., с. 393–396. During the rule of Bishop Gebey, views on the Ukrainian character of Transcarpathia crystallized; a shining example of this was Fr. Avgustyn Voloshyn, Prime Minister and President of Carpathian Ukraine (1938–1939).

Yet one more challenge facing the GCC in Sheptytsky’s time was connected with migration. The metropolitan visited immigrants in the USA, Canada, Brazil, and Argentina. Through his efforts, Ukrainians in America received hierarchs, the first of which was Soter Ortynsky.

During the Nazi occupation (1941–1944) and the Holocaust, Greek-Catholics rescued many Jews.14Юрій Скіра, Покликані: монахи Студійського уставу та Голокост, Київ: Дух і Літера, 2019. The communist authorities forbid the GCC. From the beginning, the structures of state security of the USSR at the request of Joseph Stalin and Nikita Khrushchev in 1945 arrested all the bishops in the Ukrainian SSR, headed by Metropolitan Josyf Slipyj, and on 8 March 1946 they conducted a pseudo-counsil in Lviv, which ordered a “reunion” with the ROC. They killed Mukachevo Bishop Theodore Romzha as part of a special operation of the Soviet special services.15Павел Судоплатов, Спецоперации. Лубянка и Кремль 1930–1950 годы, Москва: ОЛМА-ПРЕСС, 1998, с. 413–414. In total, approximately 1 200 priests of the GCC in Ukraine under the pressure of the communist regime went over to the ROC. Those who did not agree went into the underground, were persecuted as criminals, were injured and murdered. But the catacomb church survived: hierarchs operated in it, as did pastoral centers and monasteries. Metropolitan Slipyj [5], who lived 18 years in imprisonment, became an example of endurance. The head of the GCC did not accept an offer to become Orthodox metropolitan of Kyiv, even in exchange for his freedom. Metropolitan Slipyj was freed in 1963 thanks to the efforts of Pope John XXIII.16Йосиф Сліпий, Спомини, Львів–Рим: Видавництво Українського католицького університету, 2014, с. 160, 227–228. His Beatitude Slipyj took part in the work of the Second Vatican Council, gathered the communities of the GCC throughout the world, and until his death in 1984 implemented a program for acknowledging the patriarchal dignity of the UGCC.

Along with the movement for perestroika in the USSR, in 1987 some Greek-Catholics in Ukraine announced that they had come out from the underground, but only at the end of 1989 did the authorities agree to acknowledge the UGCC. On 25–26 June 1990, a synod of Ukrainian Greek-Catholic bishops of the whole world was held in Rome, the first since the church was forbidden. On 31 March 1991, the head of the UGCC, Myroslav Ivan Lubachivsky, returned to Ukraine. At the start of the 1990s, the Belarusian GCC also revived, headed by Apostolic Visitator and Protopriest Sergiusz Gajek. Its centers, as in the UGCC, are actively developing in cities where Belarusians have settled in the diaspora. In Lithuania, an important pastoral center of the UGCC is Holy Trinity Monastery in Vilnius, returned in 1991.17Vadimas Adadurovas, “Sunaikinimas”, in: Vadimas Adadurovas, et al., Kultūrų kryžkelė: Vilniaus Švč. Trejybės šventovė ir vienuolynas, moksl. red. Alfredas Bumblauskas, Salvijus Kulevičius, Ihoris Skočiliasas, Vilnius: Vilniaus universiteto leidykla, 2017, p. 150–151; same: Вадим Ададуров, “Закриття”, in: Вадим Ададуров, et al., На перехресті культур: Монастир і храм Пресвятої Трійці у Вільнюсі (series: Київське християнство, т. 16), наук. ред. Альфредас Бумблаускас, Сальвіюс Кулявічюс, Ігор Скочиляс, Львів: Український Католицький Університет, Львів, 2019, с. 228. Ihoris Skočiliasas, “Ukrainietiškoji perspektyva: Kijevo krikščionybės lietuviškųjų ištakų „prisiminimas“, in: Vadimas Adadurovas, op. cit., p. 243–245; same: Ігор Скочиляс, “Українська перспектива”, in: Вадим Ададуров, op. cit., с. 355–378. In Poland, there are three UGCC eparchies, and also monasteries.

On 21 August 2005, the seat of the Head of the UGCC returned to Kyiv. Its Head has the title “Major Archbishop of Kyiv-Halych”, which, according to the “Code of Canons of the Eastern Churches”, indicates a dignity equal to patriarchal. The main church of the UGCC is the Patriarchal Cathedral of the Resurrection of Christ in Kyiv, consecrated on the day of the celebration of the 1025th anniversary of the Baptism of Rus in 2013 [6]. The altar of the cathedral contains relics of the saints and apostles Peter, Paul, and Andrew the First-Called, saints popes Clement and Martin, St. Josaphat Kuntsevych the Martyr (↑), and the martyr bishops Nicholas Charnetsky and Josaphat Kotsylovsky.

Headed by Lubomyr Husar in 2001–2011, and now by Sviatoslav Shevchuk, the church is building up its structures, is an active participant in civil society, and sees its mission in defending human rights. The UGCC has more than 5 500 000 faithfuls throughout the world. In Ukraine there are almost 3 500 communities and more than 2 800 priests of the UGCC; the Mukachevo Greek-Catholic Eparchy has almost 450 communities and 350 priests and is temporarily directly subject to the Holy See.

Volodymyr Moroz

Basilian monks

After the third division of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, three of the four Basilian provinces ended up under the rule of the Russian Empire and one under the Habsburgs. In 1810, out of a number of monasteries within the boundaries of the Duchy of Warsaw, a fifth province was created, Chełm, which also ended up soon after as part of the empire of the Romanovs and was abolished the last of all the provinces which were under the influence of Russia, in 1864.18Нарис історії Василіянського Чину…, с. 279–300; Ісидор Патрило, Василіяни Холмської провінції (1810–1864) (series: Analecta OSBM, сер. 2, ч. 1–4, т. 14), Рим: Видавництво ОО Василіян, 1992, с. 239–258.

In 1795, the first wave of repressions against the Basilians arose in the Russian Empire: Basilian monasteries were liquidated under the pretext of their lack of usefulness for the state, the whole monastic administration was abolished, and the monks placed under the jurisdiction of Archbishop of Polotsk Heraclius Lisovsky. It was forbidden to admit new candidates to the monasteries without the permission of the government.19Нарис історії Василіянського Чину…, с. 253. In 1800, under Emperor Paul I, the office of protoarchimandrite was renewed, though in four years, during the rule of Alexander I, it was decisively abolished. Provincial superiors (protohegumens), who were forbidden to have any contacts with ecclesiastical institutions outside Russia, ruled the monasteries. The protohegumens had to report to local bishops about all activities which happened in the provinces. In 1832, the office of protohegumen was officially abolished and, correspondingly, the provincial chapters which elected them became superfluous. In government circles, one after another list appeared of Basilian monasteries “unnecessary for the state” and “superfluous”, and officials only needed a pretext to close them.20Ibid., с. 255–273. One pretext was the Anti-Russian November uprising of 1830–1831, participation in which monks of a number of monasteries were accused of. A negative role was also played by the lack of understanding between the white and black clergy, of which opponents of the Basilians actively took advantage. At the start of 1839, approximately 20 monasteries and 170 monks remained. Over the previous five years, more than 60 monasteries were liquidated and more than 500 monks were dispersed. A number of monks ended up in prison or exile; some of them who had come from families of the Roman Catholic rite went over to the Latin rite; some of them managed to end up in Basilian monasteries21In particular, in monasteries of Galicia the following lived to an old age: Fr. Samuel Czarnorucki (1798–1887), from Holshany, now Belarus, the author of reminiscences published in the Lviv periodical “Przegląd Lwowski”, and “the last Basilian from Lithuania”, Fr. Kyrylo Letovt (1801–1892), who lived with the reformed Basilians in Lviv. or Roman Catholic parishes in Galicia, though the majority sought shelter among family or acquaintances. After the synod of Polotsk (February 1839), dozens of Basilians went over to the Orthodox Church, and for those who refused, jails were established in separate monasteries.22Нарис історії Василіянського Чину…, с. 273–274. In this way, after 1839 the Basilian Order in the Russian Empire ceased to exist, with the exception of the territory of the autonomous Kingdom of Poland (until the Union was abolished there in 1875) (↑).

From the moment of its foundation, according to the decrees of the Torokany Chapter of 1780, 36 monasteries with 314 monks belonged to the Galicia Basilian Province of the Most Holy Redeemer. As a consequence of the ecclesiastical policy of Emperor Joseph II, the local authorities began to close monasteries which, in the opinion of the government, were not involved in socially-useful work – they didn’t run parishes or schools. In 1826, the province had a total of 14 monasteries. The number of monks also decreased: for a certain period there was an age requirement for admission to the monastery, monastic studies were forbidden, and older monks passed away but new monks did not enter. In 1800, the province had some 200 monks, in 1826–75, in 1834–82, in 1848–90, and from then on fewer and fewer; in 1881, at 14 monasteries there were 59 Basilians, not including novices.23Beata Lorens, “Życie codzienne w klasztorze bazyliańskim w Galicji (do 1882 roku)”, Galicja. Studia i materiały, 2018, t. 4, s. 107. A protohegumen headed the province, though the monasteries were subject to the bishops, who mostly were not interested in the life of the monks. In Galicia, the Basilians ran schools in Lavriv, Drohobych, and also in Buchach. The decline of internal discipline and lack of members to form candidates to the monastic life led to a situation in which, even when candidates came, the majority of them left the order. In the second half of the 19th century, on the part of the Holy See, church hierarchy, and the Basilians themselves there were certain attempts to exit the crisis, though they were without results. It clearly became understood that, without outside help and radical internal reform, it would be impossible to achieve the previous successes of “the golden age”.24Єронім Грім, “Василіянський Чин у другій пол. XIX a. Шлях до Добромильської реформи (1882–1904)”, in: Календар «Світла» на рік Божий 2017, Winnipeg: Видавництво ОО Василіян, 2017, с. 94–113.

It was at the initiative of Protohegumen Fr. Klemens Sarnicki and after the detailed visitation by Metropolitan Joseph Sembratovych of the Basilian monasteries that Pope Leo XIII on 12 May 1882 issued the apostolic letter “Singulare praesidium”, in which he began and entrusted to the Fathers of the Society of Jesus the task of the monastic reform of the Basilians in Galicia. On 15 June 1882, at the Dobromyl monastery the Jesuit Fathers assumed the formation of the Basilian novitiate. Seeing the good example of the Dobromyl monks, other monasteries gradually joined in the reform. Officially, the Dobromyl reform (named after the monastery in the city of Dobromyl) lasted 22 years and ended on 10 September 1904. Participating in the reform of the Basilian Order in six monasteries over 22 years were 47 Jesuits: 34 priests, 2 students, and 11 lay brothers.

The end of the 19th to the start of the 20th centuries was marked by a great wave of immigration of Ukrainians of Galicia to South and North America. At the call of the Church, Basilian missionaries followed the immigrants – in 1897 to Brazil and in 1902 to Canada. There they founded monasteries and laid the foundations for the creation of Basilian provinces and ecclesiastical structures. From 1920 to 1932, Basilians of Galicia conducted reforms of the Province of St. Nicholas in Transcarpathia, which to that time had been a separate administrative unit, not belonging to Basilian Order, which was established by Metropolitan Josyf Veliamyn Rutsky. As a consequence of this reform, the order became international, because it united in one monastic structure Ukrainians, Romanians, Slovaks, and Hungarians. The monks were educators in religious educational institutions: from 1904 at the Pontifical College of St. Josaphat in Rome, from 1920 at the Lviv seminary, and from 1924 at the Zagreb seminary, and they helped establish women’s congregations, the Sisters Servants and the Sisters Myrrhbearers. In June 1931 at the General Chapter in Dobromyl, the first archimandrite of the Basilian Order after the reform was elected. This year the division of the order into separate provinces began. From 12 May 1932, the official name of the order was the Basilian Order of St. Josaphat [7].25Нарис історії Василіянського Чину…, с. 324–371; Добромильська реформа і відродження Української церкви, ред. Артемій Новіцький, Ярослав Левків, Олександра Левків, Львів: Місіонер, 2003. In 1938, the Basilian Order was composed of three provinces: Galicia (378 monks); Transcarpathia, to which monks of Yugoslavia and Hungary also belonged (all together 100 monks); and American-Canadian (92 monks), and two vice-provinces, Brazil (14 monks) and Romania (39 monks).26Catalogus Ordinis Basiliani Sancti Iosaphat Provinciae Haliciensis SS. Salvatoris ineunte anno 1939, Leopolis: Typographia PP. Basilianorum in Zowkwa, 1939, p. 29.

After the Second World War, the Greek-Catholic Church was forbidden in the countries of Central and Eastern Europe in which communist governments had been established. Small groups of monks from Ukraine, Poland, and Czechoslovakia immigrated to the West. The rest shared the fate of the people and as confessors of the faith conducted monastic life and ministry in illegal conditions and all the monasteries were fully closed. During the first decade after the war, a significant amount of monks were imprisoned. Some perished during or after torture. From the end of the 1950s to the start of the 1960s, the activities of the Basilians decreased in Poland, Czechoslovakia, and Hungary, while in Romania and Ukraine the underground period lasted to the fall of communist regimes at the start of the 1990s.

In Argentina, Brazil, the USA, Canada, and Rome, where the main administrative center was located, the Basilian Order had the opportunity to successfully develop in various directions: scholarship and publishing, formation, and pastoral activities. After the legalization of the UGCC in Ukraine, the Basilians from Brazil, Poland, and the former Yugoslavia came to help renew the Province of the Most Holy Redeemer, which had perhaps most greatly suffered during the years of the communist regime. In the first decade of the renewal of the activities of the order, the Basilians for the first time in a long period went beyond the boundaries of Galicia to Volhynia and central-eastern Ukraine, where eight monasteries now operate (Volodymyr-Volynskyi, Lutsk, Kamianets-Podilskyi, Bar, Kyiv, Pokotylivka, Zvanivka, and Kherson), and they also renewed their activities in the cradle of the Basilian Order, Holy Trinity Monastery in Vilnius.

As of 2021, there are 512 Basilian monks in the world,27Catalogo dell’Ordine Basiliano di San Giosafat 2021, 2021, t. 36, p. 172. who have monastic centers in 13 countries (Argentina, Brazil, Canada, Ukraine, Hungary, Italy, Lithuania, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Serbia, Slovakia and the USA). The Basilian Order of St. Josaphat is present in six churches sui juris: the Ukrainian Greek-Catholic Church, the Mukachevo Greek-Catholic Eparchy, the Hungarian Greek-Catholic Church, the Slovak Greek-Catholic Church, the Romanian Greek-Catholic Church, and the Greek-Catholic Church of Croatia and Serbia. The order is composed of 10 provinces and still one more administrative unit of the order, a Basilian delegature in Portugal, is at the foundational stage.

In 1795, the first wave of repressions against the Basilians arose in the Russian Empire: Basilian monasteries were liquidated under the pretext of their lack of usefulness for the state, the whole monastic administration was abolished, and the monks placed under the jurisdiction of Archbishop of Polotsk Heraclius Lisovsky. It was forbidden to admit new candidates to the monasteries without the permission of the government.19Нарис історії Василіянського Чину…, с. 253. In 1800, under Emperor Paul I, the office of protoarchimandrite was renewed, though in four years, during the rule of Alexander I, it was decisively abolished. Provincial superiors (protohegumens), who were forbidden to have any contacts with ecclesiastical institutions outside Russia, ruled the monasteries. The protohegumens had to report to local bishops about all activities which happened in the provinces. In 1832, the office of protohegumen was officially abolished and, correspondingly, the provincial chapters which elected them became superfluous. In government circles, one after another list appeared of Basilian monasteries “unnecessary for the state” and “superfluous”, and officials only needed a pretext to close them.20Ibid., с. 255–273. One pretext was the Anti-Russian November uprising of 1830–1831, participation in which monks of a number of monasteries were accused of. A negative role was also played by the lack of understanding between the white and black clergy, of which opponents of the Basilians actively took advantage. At the start of 1839, approximately 20 monasteries and 170 monks remained. Over the previous five years, more than 60 monasteries were liquidated and more than 500 monks were dispersed. A number of monks ended up in prison or exile; some of them who had come from families of the Roman Catholic rite went over to the Latin rite; some of them managed to end up in Basilian monasteries21In particular, in monasteries of Galicia the following lived to an old age: Fr. Samuel Czarnorucki (1798–1887), from Holshany, now Belarus, the author of reminiscences published in the Lviv periodical “Przegląd Lwowski”, and “the last Basilian from Lithuania”, Fr. Kyrylo Letovt (1801–1892), who lived with the reformed Basilians in Lviv. or Roman Catholic parishes in Galicia, though the majority sought shelter among family or acquaintances. After the synod of Polotsk (February 1839), dozens of Basilians went over to the Orthodox Church, and for those who refused, jails were established in separate monasteries.22Нарис історії Василіянського Чину…, с. 273–274. In this way, after 1839 the Basilian Order in the Russian Empire ceased to exist, with the exception of the territory of the autonomous Kingdom of Poland (until the Union was abolished there in 1875) (↑).

From the moment of its foundation, according to the decrees of the Torokany Chapter of 1780, 36 monasteries with 314 monks belonged to the Galicia Basilian Province of the Most Holy Redeemer. As a consequence of the ecclesiastical policy of Emperor Joseph II, the local authorities began to close monasteries which, in the opinion of the government, were not involved in socially-useful work – they didn’t run parishes or schools. In 1826, the province had a total of 14 monasteries. The number of monks also decreased: for a certain period there was an age requirement for admission to the monastery, monastic studies were forbidden, and older monks passed away but new monks did not enter. In 1800, the province had some 200 monks, in 1826–75, in 1834–82, in 1848–90, and from then on fewer and fewer; in 1881, at 14 monasteries there were 59 Basilians, not including novices.23Beata Lorens, “Życie codzienne w klasztorze bazyliańskim w Galicji (do 1882 roku)”, Galicja. Studia i materiały, 2018, t. 4, s. 107. A protohegumen headed the province, though the monasteries were subject to the bishops, who mostly were not interested in the life of the monks. In Galicia, the Basilians ran schools in Lavriv, Drohobych, and also in Buchach. The decline of internal discipline and lack of members to form candidates to the monastic life led to a situation in which, even when candidates came, the majority of them left the order. In the second half of the 19th century, on the part of the Holy See, church hierarchy, and the Basilians themselves there were certain attempts to exit the crisis, though they were without results. It clearly became understood that, without outside help and radical internal reform, it would be impossible to achieve the previous successes of “the golden age”.24Єронім Грім, “Василіянський Чин у другій пол. XIX a. Шлях до Добромильської реформи (1882–1904)”, in: Календар «Світла» на рік Божий 2017, Winnipeg: Видавництво ОО Василіян, 2017, с. 94–113.

It was at the initiative of Protohegumen Fr. Klemens Sarnicki and after the detailed visitation by Metropolitan Joseph Sembratovych of the Basilian monasteries that Pope Leo XIII on 12 May 1882 issued the apostolic letter “Singulare praesidium”, in which he began and entrusted to the Fathers of the Society of Jesus the task of the monastic reform of the Basilians in Galicia. On 15 June 1882, at the Dobromyl monastery the Jesuit Fathers assumed the formation of the Basilian novitiate. Seeing the good example of the Dobromyl monks, other monasteries gradually joined in the reform. Officially, the Dobromyl reform (named after the monastery in the city of Dobromyl) lasted 22 years and ended on 10 September 1904. Participating in the reform of the Basilian Order in six monasteries over 22 years were 47 Jesuits: 34 priests, 2 students, and 11 lay brothers.

The end of the 19th to the start of the 20th centuries was marked by a great wave of immigration of Ukrainians of Galicia to South and North America. At the call of the Church, Basilian missionaries followed the immigrants – in 1897 to Brazil and in 1902 to Canada. There they founded monasteries and laid the foundations for the creation of Basilian provinces and ecclesiastical structures. From 1920 to 1932, Basilians of Galicia conducted reforms of the Province of St. Nicholas in Transcarpathia, which to that time had been a separate administrative unit, not belonging to Basilian Order, which was established by Metropolitan Josyf Veliamyn Rutsky. As a consequence of this reform, the order became international, because it united in one monastic structure Ukrainians, Romanians, Slovaks, and Hungarians. The monks were educators in religious educational institutions: from 1904 at the Pontifical College of St. Josaphat in Rome, from 1920 at the Lviv seminary, and from 1924 at the Zagreb seminary, and they helped establish women’s congregations, the Sisters Servants and the Sisters Myrrhbearers. In June 1931 at the General Chapter in Dobromyl, the first archimandrite of the Basilian Order after the reform was elected. This year the division of the order into separate provinces began. From 12 May 1932, the official name of the order was the Basilian Order of St. Josaphat [7].25Нарис історії Василіянського Чину…, с. 324–371; Добромильська реформа і відродження Української церкви, ред. Артемій Новіцький, Ярослав Левків, Олександра Левків, Львів: Місіонер, 2003. In 1938, the Basilian Order was composed of three provinces: Galicia (378 monks); Transcarpathia, to which monks of Yugoslavia and Hungary also belonged (all together 100 monks); and American-Canadian (92 monks), and two vice-provinces, Brazil (14 monks) and Romania (39 monks).26Catalogus Ordinis Basiliani Sancti Iosaphat Provinciae Haliciensis SS. Salvatoris ineunte anno 1939, Leopolis: Typographia PP. Basilianorum in Zowkwa, 1939, p. 29.

After the Second World War, the Greek-Catholic Church was forbidden in the countries of Central and Eastern Europe in which communist governments had been established. Small groups of monks from Ukraine, Poland, and Czechoslovakia immigrated to the West. The rest shared the fate of the people and as confessors of the faith conducted monastic life and ministry in illegal conditions and all the monasteries were fully closed. During the first decade after the war, a significant amount of monks were imprisoned. Some perished during or after torture. From the end of the 1950s to the start of the 1960s, the activities of the Basilians decreased in Poland, Czechoslovakia, and Hungary, while in Romania and Ukraine the underground period lasted to the fall of communist regimes at the start of the 1990s.

In Argentina, Brazil, the USA, Canada, and Rome, where the main administrative center was located, the Basilian Order had the opportunity to successfully develop in various directions: scholarship and publishing, formation, and pastoral activities. After the legalization of the UGCC in Ukraine, the Basilians from Brazil, Poland, and the former Yugoslavia came to help renew the Province of the Most Holy Redeemer, which had perhaps most greatly suffered during the years of the communist regime. In the first decade of the renewal of the activities of the order, the Basilians for the first time in a long period went beyond the boundaries of Galicia to Volhynia and central-eastern Ukraine, where eight monasteries now operate (Volodymyr-Volynskyi, Lutsk, Kamianets-Podilskyi, Bar, Kyiv, Pokotylivka, Zvanivka, and Kherson), and they also renewed their activities in the cradle of the Basilian Order, Holy Trinity Monastery in Vilnius.

As of 2021, there are 512 Basilian monks in the world,27Catalogo dell’Ordine Basiliano di San Giosafat 2021, 2021, t. 36, p. 172. who have monastic centers in 13 countries (Argentina, Brazil, Canada, Ukraine, Hungary, Italy, Lithuania, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Serbia, Slovakia and the USA). The Basilian Order of St. Josaphat is present in six churches sui juris: the Ukrainian Greek-Catholic Church, the Mukachevo Greek-Catholic Eparchy, the Hungarian Greek-Catholic Church, the Slovak Greek-Catholic Church, the Romanian Greek-Catholic Church, and the Greek-Catholic Church of Croatia and Serbia. The order is composed of 10 provinces and still one more administrative unit of the order, a Basilian delegature in Portugal, is at the foundational stage.

Fr. Yeronim Hrim, OSBM

Išnašos:

| 1. | ↑ | Нестор Мизак, Андрій Яремчук, Нарис історії УГКЦ на Буковині, Львів–Чернівці: Український католицький університет, 2021, с. 27. |

|---|---|---|

| 2. | ↑ | Dmytro Blazejowskyj, Historical Šematism of the Archeparchy of L’viv (1832–1944), vol. 1: Administration and parishes, Kyiv: Києво-Могилянська академія, 2004, p. 918; Dmytro Blazejowskyj, Historical Šematism of the Eparchy of Peremyšl including the Apostolic Administration of Lemkivščyna (1828–1939), Lviv: Kamenyar, 1995, p. 946; Schematismus cleri graeci ritus catholicorum dioecesis Munkácsiensis: Pro anno Domini MDCCCXXXIX, Cassoviae, 1838, p. 281; Schematismus cleri graeci ritus catholicorum dioecesis Eperiessiensis, pro anno Domini MDCCCXXXVII, Cassoviae, 1837, p. 169; Фундація Галицької митрополії у світлі дипломатичного листування Австрії та Святого Престолу 1807–1808 років: Збірник документів (series: Київське християнство, т. 19), ред. Вадим Ададуров, Львів: Видавництво Українського католицького університету, 2011. |

| 3. | ↑ | Начеркъ исторіи уніи рускои церкви зъ Римом, ред. Д. Дорожинскій, Львôвъ: Накладомъ комітету ювилейного, изъ типографіи Ставропигійского института, 1896, с. 82; В. Ленцик, “Українсько-Католицька Церква в Росії до її ліквідації (1772–1839/75)”, Берестейська унія (1596–1996): статті й матеріали, Львів: Логос, 1996, с. 98; Marian Radwan, Kościoł greckokatolicki w zaborze rosyjskim około 1803 roku, Lublin: Instytut Europy Środkowo-Wschodniej, 2003, s. 15. |

| 4. | ↑ | Вікторія Білик, Оксана Карліна, Жива спільнота в імперському світі: Луцька греко-унійна єпархія кінця XVIII–першої третини ХІХ століть (series: Київське християнство, т. 13), Львів: Видавництво Українського католицького університету, 2018, с. 86–109; Валентина Лось, Уніатська Церква на Правобережній Україні наприкінці XVIII – першій половині ХІХ ст.: організаційна структура та культурно-релігійний аспект, Київ: Друкарня Національної бібліотеки України імені В. І. Вернадського, 2013, с. 81; Святлана Марозава, Уніяцкая Царква у̌ этнакальтурным развіцці Бєларусі (1596–1839 гады), Гродна: ГрДУ, 2001, с. 226–237. |

| 5. | ↑ | Надія Стоколос, Руслан Шеретюк, Драма Церкви, Рівне: ПП Дятлик М.С, 2012, с. 116. |

| 6. | ↑ | Анатолій Свидницький, Оповідання. Нариси та статті, Київ: А. С. К., 2006, с. 402, 459, and other. |

| 7. | ↑ | Микола Жукалюк, Дмитро Степовик, Коротка історія перекладів Біблії українською мовою, Київ: Укр. Біблійне Тов–во, 2003, с. 65–73. |

| 8. | ↑ | Михайло Тершаковець, Маркіян Шашкевич та його ідеї на тлі українського відродження, Львів: Видавництво Українського Католицького Університету, 2021. |

| 9. | ↑ | Зорѧ Галицка 1 (1848) 1–3; Головна Руська Рада. Протоколи засідань і книга кореспонденції, ред. Олег Турій, Львів: Інститут Історії Церкви Українського Католицького Університету, 2002 с. 22–23. |

| 10. | ↑ | Олександер Баран, Питання українського патріярхату в Шашкевичівській добі, Вінніпеґ: Рада Укр. Орг. за Патріярхат Українськ. Катол. Церкві, 1984. |

| 11. | ↑ | Нарис історії Василіянського Чину святого Йосафата (series: Analecta OSBM, сер. 2, ч. 1, т. 48), Рим: Видавництво ОО Василіян, 1992, с. 324–344. |

| 12. | ↑ | Ліліана Гентош, Митрополит Шептицький: 1923–1939. Випробування ідеалів, Львів: ВНТЛ-Класика, 2015. |

| 13. | ↑ | Ibid., с. 393–396. |

| 14. | ↑ | Юрій Скіра, Покликані: монахи Студійського уставу та Голокост, Київ: Дух і Літера, 2019. |

| 15. | ↑ | Павел Судоплатов, Спецоперации. Лубянка и Кремль 1930–1950 годы, Москва: ОЛМА-ПРЕСС, 1998, с. 413–414. |

| 16. | ↑ | Йосиф Сліпий, Спомини, Львів–Рим: Видавництво Українського католицького університету, 2014, с. 160, 227–228. |

| 17. | ↑ | Vadimas Adadurovas, “Sunaikinimas”, in: Vadimas Adadurovas, et al., Kultūrų kryžkelė: Vilniaus Švč. Trejybės šventovė ir vienuolynas, moksl. red. Alfredas Bumblauskas, Salvijus Kulevičius, Ihoris Skočiliasas, Vilnius: Vilniaus universiteto leidykla, 2017, p. 150–151; same: Вадим Ададуров, “Закриття”, in: Вадим Ададуров, et al., На перехресті культур: Монастир і храм Пресвятої Трійці у Вільнюсі (series: Київське християнство, т. 16), наук. ред. Альфредас Бумблаускас, Сальвіюс Кулявічюс, Ігор Скочиляс, Львів: Український Католицький Університет, Львів, 2019, с. 228. Ihoris Skočiliasas, “Ukrainietiškoji perspektyva: Kijevo krikščionybės lietuviškųjų ištakų „prisiminimas“, in: Vadimas Adadurovas, op. cit., p. 243–245; same: Ігор Скочиляс, “Українська перспектива”, in: Вадим Ададуров, op. cit., с. 355–378. |

| 18. | ↑ | Нарис історії Василіянського Чину…, с. 279–300; Ісидор Патрило, Василіяни Холмської провінції (1810–1864) (series: Analecta OSBM, сер. 2, ч. 1–4, т. 14), Рим: Видавництво ОО Василіян, 1992, с. 239–258. |

| 19. | ↑ | Нарис історії Василіянського Чину…, с. 253. |

| 20. | ↑ | Ibid., с. 255–273. |

| 21. | ↑ | In particular, in monasteries of Galicia the following lived to an old age: Fr. Samuel Czarnorucki (1798–1887), from Holshany, now Belarus, the author of reminiscences published in the Lviv periodical “Przegląd Lwowski”, and “the last Basilian from Lithuania”, Fr. Kyrylo Letovt (1801–1892), who lived with the reformed Basilians in Lviv. |

| 22. | ↑ | Нарис історії Василіянського Чину…, с. 273–274. |

| 23. | ↑ | Beata Lorens, “Życie codzienne w klasztorze bazyliańskim w Galicji (do 1882 roku)”, Galicja. Studia i materiały, 2018, t. 4, s. 107. |

| 24. | ↑ | Єронім Грім, “Василіянський Чин у другій пол. XIX a. Шлях до Добромильської реформи (1882–1904)”, in: Календар «Світла» на рік Божий 2017, Winnipeg: Видавництво ОО Василіян, 2017, с. 94–113. |

| 25. | ↑ | Нарис історії Василіянського Чину…, с. 324–371; Добромильська реформа і відродження Української церкви, ред. Артемій Новіцький, Ярослав Левків, Олександра Левків, Львів: Місіонер, 2003. |

| 26. | ↑ | Catalogus Ordinis Basiliani Sancti Iosaphat Provinciae Haliciensis SS. Salvatoris ineunte anno 1939, Leopolis: Typographia PP. Basilianorum in Zowkwa, 1939, p. 29. |

| 27. | ↑ | Catalogo dell’Ordine Basiliano di San Giosafat 2021, 2021, t. 36, p. 172. |

Sources of illustrations:

| 1. | Held in: LNDM, LNDM T 4482 (Available at: Lietuvos integrali muziejų informacinė sistema, www.limis.lt/greita-paieska/perziura/-/exhibit/preview/20000001729965?s_id=lT538JyuBItDk8Yz&s_ind=29&valuable_type=EKSPONATAS, accessed: 2021 12 01). |

| 2. | Published in: Lietuva medaliuose = Lithuania in medals: XVI a.–XX a. pradžia, sud. Vincas Ruzas, Vilnius: Vaga, 1998, p. 157 (il. 355, 356) [Held in LDM]; Награды императорской России 1702–1917 гг., available at: http://medalirus.ru/stati/medal-na-vossoedinenie-uniatov-s-pravoslavnoyu-tserkovyu.php, accessed: 2021 12 01. |

| 3. | Published in: “Преосвященный Маркелль”, Нива, 1900, no. 15, с. 301. |

| 4. | Published in: Władyka świętojurski: rzecz o arcybiskupie Andrzeju Szeptyckim, 1865–1944, Warszawa: Instytut Wydawniczy Związków Zawodowych, 1985 (Available at: Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Andrzej_Szeptycki_(a).jpg, accessed: 2021 12 01). |

| 5. | Published in: Wikimedia Commons, available at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Cardinal_Josyp_Slipyj.jpg, accessed: 2021 12 01. |

| 6. | Published in: Ibid., https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Собор_Воскресения_Христова_Киев_1.jpg, accessed: 2021 12 01. |

| 7. | Published in: Ibid., https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:POL_CoA_bazylianie.svg, accessed: 2021 12 01. |