In 2014, a commission of specialists looked at the premises underneath Holy Trinity Church. In the crypt under the great altar, coffins lying together, out of order, were found, and among them separate boards of coffins in disarray, human bones, brick fragments, and garbage [1, 2]. Some of the coffins appeared seriously damaged by time. The specialists decided to put the crypt in order, after they conducted necessary scholarly research. The History Faculty of Vilnius University (headed by Prof. Albinas Kuncevičius) did this in 2015–2016.1See: Albinas Kuncevičius, et al., “Vilniaus bazilijonų Švč. Trejybės bažnyčios unitų karstų tyrimai”, in: Archeologiniai tyrinėjimai Lietuvoje 2015 metais, Vilnius: Lietuvos archeologijos draugija, 2016, p. 237–247; Albinas Kuncevičius, “Vilniaus bazilijonų Švč. Trejybės bažnyčios unitų palaidojimų tyrimai 2016 m.”, in: Archeologiniai tyrinėjimai Lietuvoje 2017 metais, Vilnius: Lietuvos archeologijos draugija, 2018, p. 265–268. Research reports: Albinas Kuncevičius, Vilniaus bazilijonų vienuolyno statinių ansamblio (681) Švč. Trejybės bažnyčios (27316), Vilniaus m. sav., Vilniaus m., Aušros Vartų g. 7B, 2015 metų archeologinių žvalgymų ataskaita, Vilnius, 2015; Albinas Kuncevičius, Vilniaus bazilijonų vienuolyno statinių ansamblio Švč. Trejybės bažnyčios (27316) teritorijos, Vilniaus m. sav., Vilniaus m., Aušros Vartų g. 7B, 2016 metų detaliųjų archeologinių tyrimų ataskaita, Vilnius, 2016. The research was varied (in history, archeology, anthropology, architecture, and art history) [3] and helped determine not only the order of burial of Basilian monks but the manner of their lives, dining, state of health, etc.

In the historical sources, premises for burial like this are called the brothers’ crypt (sklep Bracki). It is only possible to get to it through an entrance located in the floor of the church directly in front of the great altar. Descent is through a stairway. The crypt itself in cross-section has the form of a half-cylinder (length 8.7 meters, width 5.8 meters, height approx. 4.3 meters); in its back wall is an opening for ventilation or illumination. When one considers the masonry, the construction could have happened in several stages: the back wall of the premises seems older than the side walls, and the latter are older than the vaults. Fragments of the previous floor are preserved. A “path” was noticed, which led from the entrance to the center. It was composed of plates of metal burnt and ruined over the centuries, less than 2 centimeters thick and dimensions approximately 20×40 centimeters, pieces of thick tin or remnants of the shackles of former metal doors (?). The plates created an almost solid path which, clearly, ran through the rows of coffins when they were arranged neatly. In 2015, the mentioned coffins were found at this level of the floor. Near the entrance to the crypt, 0.7 meter lower than the last step, a small area of flooring appeared, laid with unglazed, red floor tiles.

Fifteen coffins lay chaotically together at the entrance. It is supposed that they ended up here very late. At the end of the crypt, the researchers saw coffins placed with disorder in three or four levels, to the very top of the crypt. Among them were small pieces from construction work and human bones which ended up in the crypt (they were tossed there) through a ventilation opening, most probably during some repair of the church or cleaning of the churchyard. Slightly fewer coffins were inside the premises.

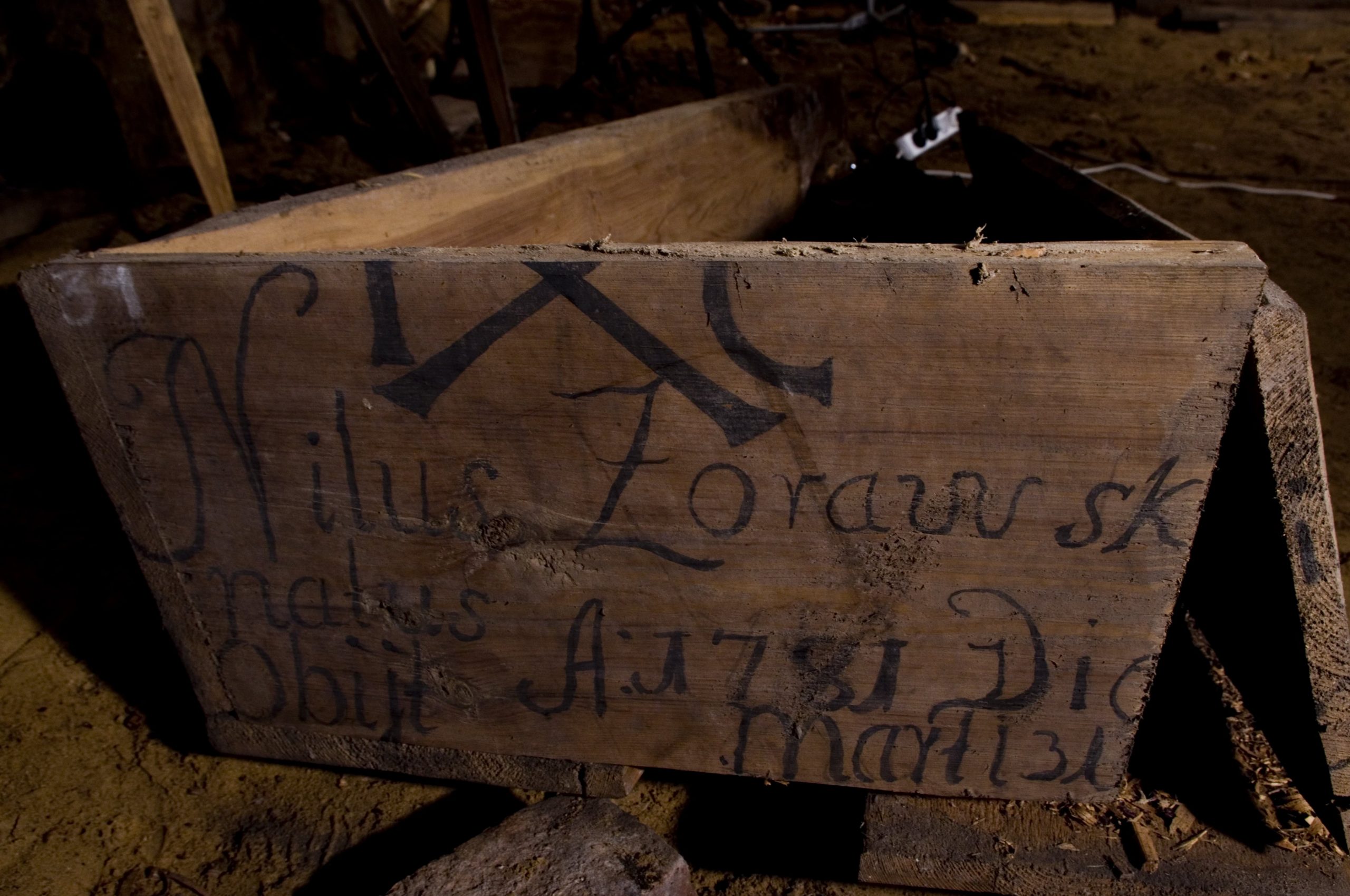

In 2015, 53 coffins with corpses were found in the crypt (24 of them were preserved fairly well, the others only partially) and individual bones of approximately 60 persons. All the coffins with their boards, approx. 1.8–2 meters, in width 0.5–0.7 meters (in the heads) and 0.4–0.5 meters (in the legs), and a height of 0.6 meters (with age). Some of them had hooks; the rest, plausibly, were “lost” or ruined during the process of re-burial. The hook was attached to the lower part of the coffin with wooden pegs or, in rare cases, metal nails. Some of the coffins were adorned with monograms of Jesus or the Most Holy Mother of God (Latin or Greek); some had various images (for example, a skull and bones in a cross shape beneath). Still other coffins were painted red with white crosses on them, etc. On 14 coffins, inscriptions were noted (in the Latin or Polish languages), which laconically recorded the most important biographical facts about the deceased [4, 5, 6]. For example: “The Honored Father Florianus Walicki, [monk] of the Order of St. Basil the Great, superior of Lidsk [monastery], general procurator. Died on 6 July 1750 [having] 37 years, [he lived] 11 years as a monk.”

The burial clothes (↑) and inscriptions (↑) demonstrate that the Basilians buried here died in 1717–1788. It is also possible to state that this was not the first place or the order of their burial. The last time the coffins were taken into the crypt, clearly, was in Soviet times, when, in the church closed to the faithful, a scholarly laboratory of the State Engineering Institute of Construction was established, to research the quality of reinforced concrete constructions. In this period, the coffins with remains which, before that, possibly, were in various crypts of the church, were transferred to these premises. In a few of the coffins which stood closer to the entrance, newspapers from 1965, used as rags, were found.

In the process of research, it was determined that the burials were done under the bottom of the crypt. In 2016, in this level 18 coffins with remains and the remains of two bodies without coffins were found. Most likely, they were not buried at the same time, though fairly neatly: they were set in rows near the side walls of the crypt, with heads towards its back wall (facing the altar of the church) or towards the entrance, being buried at a depth of 0.5 to 1 meter. All these coffins were without ornaments or inscriptions. The majority of those buried in them were Basilian monks. The burial clothing indicates this, epitrachelion and six paramandyias. There was a woman, approximately 50 years old, in only one of the coffins: she was buried in a hood made of woolen materials (fragments of which remained), artificial flowers placed on the body (petals made from thin silk and lacy fabric, stems of metal wire) and embroidered detail with the monogram of Christ “IHS.” The measurements of yet another coffin (approx. 1×0, 3×0, 2 meters, the remains have not been preserved) allow one to suppose that a child was buried here. Because the oldest burial inside the crypt (on the bottom), when one considers the inscriptions, is connected with 1717, it is entirely possible that all the coffins and remains buried in the crypt date to the period before 1717.

After close inspection, the remains were re-buried in a re-arranged crypt (renewed and adapted for re-burial in 2017–2020) [7, 8, 9] (↑).

Albinas Kuncevičius

Išnašos:

| 1. | ↑ | See: Albinas Kuncevičius, et al., “Vilniaus bazilijonų Švč. Trejybės bažnyčios unitų karstų tyrimai”, in: Archeologiniai tyrinėjimai Lietuvoje 2015 metais, Vilnius: Lietuvos archeologijos draugija, 2016, p. 237–247; Albinas Kuncevičius, “Vilniaus bazilijonų Švč. Trejybės bažnyčios unitų palaidojimų tyrimai 2016 m.”, in: Archeologiniai tyrinėjimai Lietuvoje 2017 metais, Vilnius: Lietuvos archeologijos draugija, 2018, p. 265–268. Research reports: Albinas Kuncevičius, Vilniaus bazilijonų vienuolyno statinių ansamblio (681) Švč. Trejybės bažnyčios (27316), Vilniaus m. sav., Vilniaus m., Aušros Vartų g. 7B, 2015 metų archeologinių žvalgymų ataskaita, Vilnius, 2015; Albinas Kuncevičius, Vilniaus bazilijonų vienuolyno statinių ansamblio Švč. Trejybės bažnyčios (27316) teritorijos, Vilniaus m. sav., Vilniaus m., Aušros Vartų g. 7B, 2016 metų detaliųjų archeologinių tyrimų ataskaita, Vilnius, 2016. |

|---|