Vilnius as Jerusalem. As a rule, they compare the names Vilnius and Jerusalem because of the importance of both of these cities for Jewish culture. In this aspect, the Lithuanian capital was glorified above all thanks to the legendary activities of the Vilna Gaon (1720–1797). However, the idea of Holy Jerusalem can be traced not only in the history of the Jewish community of Vilnius but in the city’s Christian tradition. Let us consider its Ostra Brama (Gate of Dawn), where shrines of three confessions are neighbors: the Roman Catholic Ostra Brama Chapel with the famous “Our Lady of Ostra Brama” and the Church of St. Teresa and the Carmelite monastery; the Orthodox Holy Spirit Church with monastery of the same name; the Uniate Holy Trinity Church and monastery [1]. Not only the shrine but the Churches and religious communities are in close contact: the Uniate metropolitan with the Basilians, Orthodox of the city are directly subordinate to the patriarch of Constantinople, and the Roman Catholic bishop of Vilnius with the Carmelites. Going through the streets to the castle and Green Bridge, we encounter two influential Protestant communities – Calvinist boyars and Lutherans, and also Armenians and Jews who found shelter in the jurisdiction of the local Roman Catholic hierarch (↑). And somewhere close are Karaites, Tatars, and Old Believers. Also eloquent here is the legacy of the genius of the Vilnius baroque, Johann Christoph Glaubitz (approx. 1700–1767): though a Lutheran, he created not only for his fellow believers but for Orthodox (the iconostasis of Holy Spirit Church), Uniates (the Basilian gate), Roman Catholics (the churches of saints John, Catherine, and perhaps of the Missionary Fathers), and Jews (the interior of the Great Synagogue).1See more: Stanisław Lorentz, Jan Krzysztof Glaubitz, architekt wileński XVIII w. Materiały do biografii i twórczości (series: Prace z Historii Sztuki, t. 3), Warszawa: Towarzystwo Naukowe Warszawskie, 1937; Vladas Drėma, Dingęs Vilnius = Lost Vilnius, Vilnius: Vaga, 1991; Vladas Drėma, Vilniaus Šv. Jono bažnyčia, Vilnius: R. Paknio leidykla, 1997.

Eastern Christianity is a significant component of the idea of Jerusalem. Unfortunately, in the modern era Lithuanians began to identity Eastern Christianity with Muscovite Orthodox, who began to dominate in the 19th century. From then on, Eastern Christianity was long associated with, and is perhaps still associated with:

- the church of the Romanovs at the top of Basanivicius Street, built in 1913 on the occasion of the 300th anniversary of the Romanov Dynasty;

- the Orthodox church at the end of Gedyminas Prospect, which is across from the Roman Catholic cathedral, which stands at the other end of this street;

- the end of the church union after the uprising of 1831 and the transformation of St. Casimir Roman Catholic Church to an Orthodox cathedral;

- the reincarnation of the dukes Ostrogski as the main “zealots of Orthodoxy.”2Афанасий В. Ярушевич, Ревнитель православия князь Константин Иванович Острожский (1461–1530) и православная Литовская Русь в его время, Смоленск: [s. n.], 1896.

This is the image of Vilnius and Eastern Christianity that tsarist Russia formed. In parallel, before the war the Lithuanians’ national treatment of the history of their capital appears: it views all its past as essentially Lithuanian or looks only for Lithuanians in it. Now, however, an alternative, multi-perspective view is being created, the foundations of which were laid by noted poet and publicist Tomas Ventslova and, in the academic world, Edvardas Gudavičius.3See more: Alfredas Bumblauskas, “Lietuvos istoriniai „didieji pasakojimai” ir Vilniaus paveldas”, in: Naujasis Vilniaus perskaitymas: didieji Lietuvos istoriniai pasakojimai ir daugiakultūrinis miesto paveldas (series: Specialus „Lietuvos istorijos studijų“ leidinys, t. 5), red. Alfredas Bumblauskas, Šarūnas Liekis, Grigorijus Potašenko, Vilnius: Vilniaus universiteto leidykla, 2009, p. 15–47.

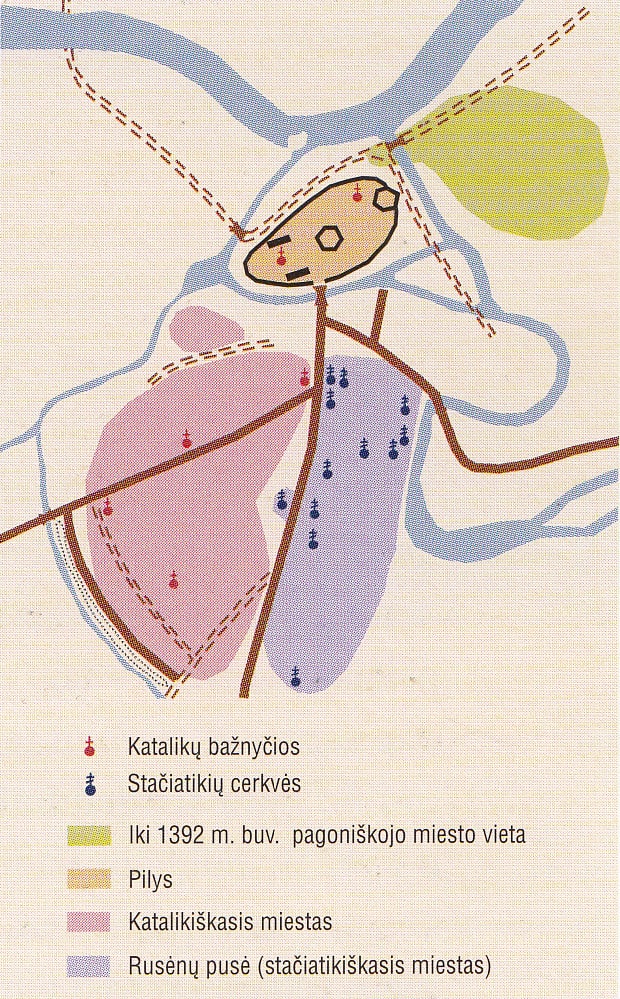

Realizing the limits of previous views, historians of our time wanted to turn attention to a forgotten group of inhabitants of the GDL, Christians of the Eastern rite. So arose the concept civitas Ruthenica, which the Polish scholar Józef Maroszek developed. He presented the jurisdictional division of Vilnius in the form of “puzzles”, separating the two important parts of civitas Ruthenica, the “metropolitan city” and the Ruthenian Magdeburg city. The researcher proposed a hypothesis about the relations of the “metropolitan city” with the policy of Grand Duke of Lithuania Vytautas and with his associate Grzegorz Cambłak (he has in mind the council of 1415 and the embassy to Constance in 1416–1417).4Józef Maroszek, Dziedzictwo unii kościelnej w krajobrazie kulturowym Podlasia, Białystok: Regionalny Ośrodek Studiów i Ochrony Srodowiska Kulturowego w Białymstoku, 1996; Józef Maroszek, Pogranicze Litwy i Korony w planach króla Zygmunta Augusta, Białystok: Uniwersytet w Białymstoku, 2000. Then archeologist Gediminas Vaitkevičius and his colleagues made a true revolution in the understanding of the early history of Vilnius: the pagan city was found, and also the Ruthenian (from the times of Grand Duke Vytautas) and German (from the times of Grand Duke Algirdas) suburbs.5Kęstutis Katalynas, Gediminas Vaitkevičius, “Vilniaus plėtra iki XIV a.”, Kultūros paminklai, 2001, t. 8, p. 68–76; Kęstutis Katalynas, Gediminas Vaitkevičius, Vilniaus plėtra XIV–XVII a., Vilnius: Diemedis, 2006, p. 53–54, 65–69; Kęstutis Katalynas, Gediminas Vaitkevičius, “Rozwój Wilna w XIV wieku w świetle badań archeologicznych”, Kwartalnik Historii Kultury Materialnej, 2002, vol. 50, no. 1, s. 3–10; Gediminas Vaitkevičius, Vilniaus įkūrimas (series: Vilniaus sąsiuviniai, t. 1), Vilnius: Lietuvos nacionalinis muziejus, 2010, p. 49–66. It was discovered that the early Orthodox suburb of Vilnius in the period of Vytautas’s rule (1392–1430), known already in the age of Vytenis (approx. 1295–1316), transformed into civitas Ruthenica.6Дaрюс Баронас, “Древнейшие следы пребывания русских в Вильнюсе”, in: Slavistica Vilnensis (series: Kalbotyra, t. 53), 2004, p. 161‒166; Rytis Jonaitis, “Orthodox Churches in the Civitas Rutenica Area of Vilnius: The Question of Location”, Archaeologia Baltica, 2011, t. 16, p. 110‒128. Now we know that it was in Vilnius that the Kyivan metropolitans had their true see, which they had neither in Novohrudok nor in Kyiv [2, 3]. After the invasion of the Tatars in 1480, Kyiv for the Ruthenian hierarchs remained, perhaps, only in title. Holy Trinity Monastery in Vilnius was founded in the Magdeburg Ruthenian city and did not directly belong to “the metropolitan city”, though the superiors of this monastery very often became metropolitans. So their history is a part of or is the context of the theme of the Basilians in Vilnius.

The “discovery” of Eastern Christianity in the GDL allows one again to look at the phenomenon itself of the union of churches and the union process in Central and Eastern Europe.7Krikščionybės Lietuvoje istorija, sud. Vytautas Ališauskas, Vilnius: Aidai, 2006; Remigijus Černius, “Bažnytinė unija”, in: Lietuvos Didžiosios Kunigaikštijos kultūra: tyrinėjimai ir vaizdai, sud. Vytautas Ališauskas, et al., Vilnius: Aidai, 2001, p. 72–93; Darius Baronas, “Stačiatikiai”, in: Lietuvos Didžiosios Kunigaikštijos kultūra…, 674–689. The Lithuanian metropolitan see, created in 1415 for Grzegorz Cambłak, played a significant role in the confessional policy of Vytautas and Jogaila. In 1418 at the Ecumenical Council of Constance, this Orthodox hierarch not only celebrated an ecumenical divine service but also proclaimed to all Europe the idea of church union, before the Council of Florence of 1439. With this in mind, concepts about informal church union in the GDL before 1596 gain exceptional weight.8Oskar Halecki, “Dzieje Unji Kościelnej w Wielkim Księstwie Litewskiem (do 1596)”, in: Pamiętnik VI zjazdu historyków polskich w Wilnie 17–20 września 1935 r., t. 1:Referaty, red. F. Pohorecki, Lwów: Polskie Towarzystwo Historyczne, 1935, s. 311–319; Oskar Halecki, From Florence to Brest (1439–1596), Rome: Sacrum Poloniae Millennium, 1958; Гянутэ Кіркене, “Інтэграцыйныя працэсы ў Вялікім Княстве Літоўскім: царкоўная унія”, Беларускі гістарычны агляд = Belarusian historical review, 2005, т. 12, сш. 1–2, с. 21–35; Genutė Kirkienė, “Supraslio vienuolyno konfesinės priklausomybės ir pobūdžio klausimas XVI a. pradžioje”, Lietuvos istorijos studijos, 2006, t. 18, p. 39–50; Genutė Kirkienė, “Ar būta stačiatikių LDK politiniame elite Aleksandro valdymo laikais?”, in: Lietuvos didysis kunigaikštis Aleksandras ir jo epocha, sud. Daiva Steponavičienė, Vilnius: Vilniaus pilių valstybinio kultūrinio rezervato direkcija, 2007, p. 123–130; Genutė Kirkienė, “Stačiatikių integracija į Lietuvos Didžiosios Kunigaikštijos visuomenę XV–XVI a.”, in: Lietuvos Didžiosios Kunigaikštijos tradicija ir paveldo „dalybos“ (series: Specialusis „Lietuvos istorijos studijų“ leidinys, t. 5), sud. Alfredas Bumblauskas, Šarūnas Liekis, Grigorijus Potašenko, Vilnius: Vilniaus universiteto leidykla, 2008, p. 157–168; Genutė Kirkienė, “Orientacja wyznaniowa i możliwości kulturalne Chodkiewiczów”, in: Studia nad reformacją, red. Elżbieta Bagińska, Piotr Guzowski, Marzena Liedke, Białystok: Uniwersytet w Białymstoku, 2010, s. 9–17. So at the turn of the 16th century, Chodkiewicz and Sapieha magnates began initiating prayer houses with two liturgies in Ikazn, Kodeń, Supraśl, and other places. These concepts explain the phenomenon of Byzantine Church Gothic, which previously was difficult to understand – it was connected with the process of uniting the Churches.

And so the Orthodox area of Vilnius spread. We know very little about contacts of the Orthodox of Vilnius, Mogilev, and Lviv in the 17th to 18th centuries. As a rule, a change in the behavior of the Orthodox of Mogilev is accented after the Moscow–Swedish “deluge.” However, outside our attention is the Cossack Hetmanate, including Hetman Ivan Mazepa and also that pupil of Vilnius University through whose efforts arose an Orthodox, though, in its essence Catholic, educational system, Peter Mogila. We will also speak little about the influence of Vilnius baroque not only on Mstsislaw (the Carmelite church of Glaubitz) but also on Ukrainian baroque, which was created by a “master of German descent” Johann-Baptist Sauer (Jan Zaor), who came from Vilnius in 1680 at the invitation of Archbishop of Chernihiv Łazarz Baranowicz.9See: Stasys Samalavičius, Almantas Samalavičius, Vilniaus Šv. Petro ir Povilo bažnyčia, Vilnius: Pilių tyrimo centras „Lietuvos pilys“, 1998, p. 174; Stasys Samalavičius, Vilniaus miesto kultūra ir kasdienybė XVII–XVIII amžiuose, Vilnius: Edukologija, 2012, p. 473; Anna Sylwia Czyż, Kościół Świętych Piotra i Pawła na Antokolu w Wilnie, Wroclaw, Warszawa, Kraków: Zakład Narodowy im. Ossolińskich, 2008, s. 33–38, 75–82, 251; Rūta Janonienė, “Sapiegų rūmų Antakalnyje architektas Giovanni Battista Frediani: biografijos bruožai”, in: Dailės ir architektūros paveldas: tyrimai, išsaugojimo problemos ir lūkesčiai (series: Acta Academiae Artium Vilnensis, t. 77–78), sud. Dalia Klajumienė, Vilnius: BALTO print, 2015, p. 13–43. Mazepa himself developed Sauer’s architectural ideas.10On this shift see: Oleksandr Ohlobyn, “Western Europe and the Ukrainian Baroque: An Aspect of Cultural Influences at the Time of Hetman Ivan Mazepa”, Annals of the Ukrainian Academy of Arts and Sciences in the U. S., 1951, vol. 1, no. 2, p. 127–137; Volodymyr Mezentsev, “Mazepa’s Palace in Baturyn: Western and Ukrainian Baroque Architecture and Decoration”, Harvard Ukrainian Studies, 2009–2010, vol. 31, no. 1–4, p. 433–470; Володимир І. Мезенцев, “Західні, українські та російські прийоми в архітектурі й декорі палацу І. Мазепи в Батурині”, Сіверщина в історії України, 2013, т. 6, с. 220–234; Лариса Горенко-Баранівська, “Гетьман І. Мазепа – фундатор закладів культури й освіти в Україні другої половини XVII – початку XVIII ст.”, Українознавство, 2002, т. 4, с. 220–223.

An attempt at generalization. The situation changed very slowly. And though Lithuanians are very aware of the fact that even before Grand Duke Mindaugas accepted Catholic baptism (1251), his son Vaišelga was baptized Orthodox (1245), that he founded the Orthodox monastery at Lavrishiv (where in the 14th century the famous Lavrishiv Gospel, the first manuscript book of the GDL, appeared),11Rima Cicėnienė, “Rankraštinė knyga Lietuvos Didžiojoje Kunigaikštystėje XIV a. pradžioje – XVI a. viduryje: sklaidos ir funkcionavimo sąlygos”, Knygotyra, 2009, t. 53, p. 7–37; Rima Cicėnienė, “LDK ankstyvoji knygos visuomenė: genezė ir raida (iki XVI a. vidurio)”, Knygotyra, 2010, t. 55, p. 7–25; Rima Cicėnienė, “LDK rankraštinės knygos mecenatai XIV a. – XVI a. viduryje”, in: Dangiškieji globėjai, žemiškieji mecenatai (series: Acta Academiae Artium Vilnensis, t. 60), sud. Jolita Liškevičienė, Vilnius: Vilniaus dailės akademijos leidykla, 2011, p. 13–24; Rima Cicėnienė, “Książka rękopiśmienna w życiu społeczeństwa w Wielkim Księstwie Litewskim w XIV – połowie XVI wieku”, Rocznik Lituanistyczny, 2015, t. 1, s. 219–250; Rima Cicėnienė, “Rankraštinių ir spausdintinių LDK XVI–XVII a. knygų pasaulis: sąsajos ir sankirtos”, Knygotyra, 2017, t. 68, p. 7–37. and so became a hagiographical hero, still, Eastern Christianity continues to be beyond the boundaries of the great narrative of Lithuania. For Lithuanians, the Orthodox saints Anthony, John, and Eustathius are still foreign, who were two centuries ahead of the holiness of Kazymyr, who is often considered the single Lithuanian saint (↑). Ignored are not only the priest-martyr from the Vilnius Jesuits Andrew Bobola, together with the newest saints, Raphael Kalinowski and Faustina Kowalska. (They are all clearly treated as representatives of “Polish” Christianity.) The Greek-Catholic bishop-martyr Josaphat Kuntsevych is ignored (↑). That Greek-Catholicism is still in all not considered something native for Lithuanians is demonstrated by the spread of ideas about the significance of confessions: for the identification of the faithful, the term “Roman Catholics” is very seldom used. Instead, the wider “Catholics” is used, which, we recall, also includes Greek-Catholics. There is, therefore, truly much work to renew the Vilnius Eastern Christian tradition in the modern cultural memory of Lithuanians.

The sad fate of the Commonwealth of both Nations can be connected with the unsuccessful project of transforming it into a Commonwealth of Three Nations with a Ukrainian (or Ruthenian) part. This unrealized alternative today is looked at mostly only through the prism of history: of the Cossacks, of the Hetmanate they created, and of the unsuccessful Hadiach Treaty of 1658. However, modern Ukrainian historians have proposed an exceptionally interesting concept, according to which the third participant, after all, existed, and this was the institution of Eastern Christianity, at first the Orthodox and later the Uniate Vilnius-Kyivan Metropolitanate. Actually, this institution provided the principles of the Ukrainian and Belarusian identity of the Commonwealth of Both Nations (↑).12Andrzej Gil, Ihor Skoczylas, Kościoły Wschodnie w państwie polsko-litewskim w procesie przemian i adaptacji: Metropolia kijowska w latach 1458–1795, Lublin–Lwów: Instytut Europy Środkowo-Wschodniej, 2014. If we consider that the Uniates of Poland, and eventually even of historical Hungary, were subject to the Vilnius Metropolitanate, we will notice how many new pages in the history of the GDL and, in particular, Lithuania can be revealed.

But let us return to Ostra Brama. In 1514 it became a triumphal arch for Konstanty Ostrogski after his victorious battle near Orsha. It has still not been determined when and why the Poles began to call this gate “Ostra” (“sharp”), but the Lithuanians “Gate of Dawn” (Aušros vartai). We recall, however, the hypothesis that we earlier put aside (at least relevant in the context of this monograph) that Ostra Brama is the brama (gate) of Ostrogski (Ostrogska brama). Thus could one of the greatest military leaders in the history of Lithuania be honored, but he already, in his time, thanked the Lord God through a votive gift for Orsha, the Ruthenian Church of the Holy Trinity [4] (↑).

Alfredas Bumblauskas

Išnašos:

| 1. | ↑ | See more: Stanisław Lorentz, Jan Krzysztof Glaubitz, architekt wileński XVIII w. Materiały do biografii i twórczości (series: Prace z Historii Sztuki, t. 3), Warszawa: Towarzystwo Naukowe Warszawskie, 1937; Vladas Drėma, Dingęs Vilnius = Lost Vilnius, Vilnius: Vaga, 1991; Vladas Drėma, Vilniaus Šv. Jono bažnyčia, Vilnius: R. Paknio leidykla, 1997. |

|---|---|---|

| 2. | ↑ | Афанасий В. Ярушевич, Ревнитель православия князь Константин Иванович Острожский (1461–1530) и православная Литовская Русь в его время, Смоленск: [s. n.], 1896. |

| 3. | ↑ | See more: Alfredas Bumblauskas, “Lietuvos istoriniai „didieji pasakojimai” ir Vilniaus paveldas”, in: Naujasis Vilniaus perskaitymas: didieji Lietuvos istoriniai pasakojimai ir daugiakultūrinis miesto paveldas (series: Specialus „Lietuvos istorijos studijų“ leidinys, t. 5), red. Alfredas Bumblauskas, Šarūnas Liekis, Grigorijus Potašenko, Vilnius: Vilniaus universiteto leidykla, 2009, p. 15–47. |

| 4. | ↑ | Józef Maroszek, Dziedzictwo unii kościelnej w krajobrazie kulturowym Podlasia, Białystok: Regionalny Ośrodek Studiów i Ochrony Srodowiska Kulturowego w Białymstoku, 1996; Józef Maroszek, Pogranicze Litwy i Korony w planach króla Zygmunta Augusta, Białystok: Uniwersytet w Białymstoku, 2000. |

| 5. | ↑ | Kęstutis Katalynas, Gediminas Vaitkevičius, “Vilniaus plėtra iki XIV a.”, Kultūros paminklai, 2001, t. 8, p. 68–76; Kęstutis Katalynas, Gediminas Vaitkevičius, Vilniaus plėtra XIV–XVII a., Vilnius: Diemedis, 2006, p. 53–54, 65–69; Kęstutis Katalynas, Gediminas Vaitkevičius, “Rozwój Wilna w XIV wieku w świetle badań archeologicznych”, Kwartalnik Historii Kultury Materialnej, 2002, vol. 50, no. 1, s. 3–10; Gediminas Vaitkevičius, Vilniaus įkūrimas (series: Vilniaus sąsiuviniai, t. 1), Vilnius: Lietuvos nacionalinis muziejus, 2010, p. 49–66. |

| 6. | ↑ | Дaрюс Баронас, “Древнейшие следы пребывания русских в Вильнюсе”, in: Slavistica Vilnensis (series: Kalbotyra, t. 53), 2004, p. 161‒166; Rytis Jonaitis, “Orthodox Churches in the Civitas Rutenica Area of Vilnius: The Question of Location”, Archaeologia Baltica, 2011, t. 16, p. 110‒128. |

| 7. | ↑ | Krikščionybės Lietuvoje istorija, sud. Vytautas Ališauskas, Vilnius: Aidai, 2006; Remigijus Černius, “Bažnytinė unija”, in: Lietuvos Didžiosios Kunigaikštijos kultūra: tyrinėjimai ir vaizdai, sud. Vytautas Ališauskas, et al., Vilnius: Aidai, 2001, p. 72–93; Darius Baronas, “Stačiatikiai”, in: Lietuvos Didžiosios Kunigaikštijos kultūra…, 674–689. |

| 8. | ↑ | Oskar Halecki, “Dzieje Unji Kościelnej w Wielkim Księstwie Litewskiem (do 1596)”, in: Pamiętnik VI zjazdu historyków polskich w Wilnie 17–20 września 1935 r., t. 1:Referaty, red. F. Pohorecki, Lwów: Polskie Towarzystwo Historyczne, 1935, s. 311–319; Oskar Halecki, From Florence to Brest (1439–1596), Rome: Sacrum Poloniae Millennium, 1958; Гянутэ Кіркене, “Інтэграцыйныя працэсы ў Вялікім Княстве Літоўскім: царкоўная унія”, Беларускі гістарычны агляд = Belarusian historical review, 2005, т. 12, сш. 1–2, с. 21–35; Genutė Kirkienė, “Supraslio vienuolyno konfesinės priklausomybės ir pobūdžio klausimas XVI a. pradžioje”, Lietuvos istorijos studijos, 2006, t. 18, p. 39–50; Genutė Kirkienė, “Ar būta stačiatikių LDK politiniame elite Aleksandro valdymo laikais?”, in: Lietuvos didysis kunigaikštis Aleksandras ir jo epocha, sud. Daiva Steponavičienė, Vilnius: Vilniaus pilių valstybinio kultūrinio rezervato direkcija, 2007, p. 123–130; Genutė Kirkienė, “Stačiatikių integracija į Lietuvos Didžiosios Kunigaikštijos visuomenę XV–XVI a.”, in: Lietuvos Didžiosios Kunigaikštijos tradicija ir paveldo „dalybos“ (series: Specialusis „Lietuvos istorijos studijų“ leidinys, t. 5), sud. Alfredas Bumblauskas, Šarūnas Liekis, Grigorijus Potašenko, Vilnius: Vilniaus universiteto leidykla, 2008, p. 157–168; Genutė Kirkienė, “Orientacja wyznaniowa i możliwości kulturalne Chodkiewiczów”, in: Studia nad reformacją, red. Elżbieta Bagińska, Piotr Guzowski, Marzena Liedke, Białystok: Uniwersytet w Białymstoku, 2010, s. 9–17. |

| 9. | ↑ | See: Stasys Samalavičius, Almantas Samalavičius, Vilniaus Šv. Petro ir Povilo bažnyčia, Vilnius: Pilių tyrimo centras „Lietuvos pilys“, 1998, p. 174; Stasys Samalavičius, Vilniaus miesto kultūra ir kasdienybė XVII–XVIII amžiuose, Vilnius: Edukologija, 2012, p. 473; Anna Sylwia Czyż, Kościół Świętych Piotra i Pawła na Antokolu w Wilnie, Wroclaw, Warszawa, Kraków: Zakład Narodowy im. Ossolińskich, 2008, s. 33–38, 75–82, 251; Rūta Janonienė, “Sapiegų rūmų Antakalnyje architektas Giovanni Battista Frediani: biografijos bruožai”, in: Dailės ir architektūros paveldas: tyrimai, išsaugojimo problemos ir lūkesčiai (series: Acta Academiae Artium Vilnensis, t. 77–78), sud. Dalia Klajumienė, Vilnius: BALTO print, 2015, p. 13–43. |

| 10. | ↑ | On this shift see: Oleksandr Ohlobyn, “Western Europe and the Ukrainian Baroque: An Aspect of Cultural Influences at the Time of Hetman Ivan Mazepa”, Annals of the Ukrainian Academy of Arts and Sciences in the U. S., 1951, vol. 1, no. 2, p. 127–137; Volodymyr Mezentsev, “Mazepa’s Palace in Baturyn: Western and Ukrainian Baroque Architecture and Decoration”, Harvard Ukrainian Studies, 2009–2010, vol. 31, no. 1–4, p. 433–470; Володимир І. Мезенцев, “Західні, українські та російські прийоми в архітектурі й декорі палацу І. Мазепи в Батурині”, Сіверщина в історії України, 2013, т. 6, с. 220–234; Лариса Горенко-Баранівська, “Гетьман І. Мазепа – фундатор закладів культури й освіти в Україні другої половини XVII – початку XVIII ст.”, Українознавство, 2002, т. 4, с. 220–223. |

| 11. | ↑ | Rima Cicėnienė, “Rankraštinė knyga Lietuvos Didžiojoje Kunigaikštystėje XIV a. pradžioje – XVI a. viduryje: sklaidos ir funkcionavimo sąlygos”, Knygotyra, 2009, t. 53, p. 7–37; Rima Cicėnienė, “LDK ankstyvoji knygos visuomenė: genezė ir raida (iki XVI a. vidurio)”, Knygotyra, 2010, t. 55, p. 7–25; Rima Cicėnienė, “LDK rankraštinės knygos mecenatai XIV a. – XVI a. viduryje”, in: Dangiškieji globėjai, žemiškieji mecenatai (series: Acta Academiae Artium Vilnensis, t. 60), sud. Jolita Liškevičienė, Vilnius: Vilniaus dailės akademijos leidykla, 2011, p. 13–24; Rima Cicėnienė, “Książka rękopiśmienna w życiu społeczeństwa w Wielkim Księstwie Litewskim w XIV – połowie XVI wieku”, Rocznik Lituanistyczny, 2015, t. 1, s. 219–250; Rima Cicėnienė, “Rankraštinių ir spausdintinių LDK XVI–XVII a. knygų pasaulis: sąsajos ir sankirtos”, Knygotyra, 2017, t. 68, p. 7–37. |

| 12. | ↑ | Andrzej Gil, Ihor Skoczylas, Kościoły Wschodnie w państwie polsko-litewskim w procesie przemian i adaptacji: Metropolia kijowska w latach 1458–1795, Lublin–Lwów: Instytut Europy Środkowo-Wschodniej, 2014. |

Sources of illustrations:

| 1. | Private collection of Marius Jovaiša. Published in: Marius Jovaiša, Neregėta Lietuva, Vilnius: MIA, 2007, p. 26. |

| 2. | Published in: Alfredas Bumblauskas, Senosios Lietuvos istorija, 1009–1795, Vilnius: R. Paknio leidykla, 2005, p. 79. |

| 3. | Private collection of Marius Jovaiša. Published in: Marius Jovaiša, op. cit., p. 28. |

| 4. | Collection of VU IF. |